Introduction

Advanced Architecture Studio V

In Advanced Architecture Studio V, each of the 18 studios creates its own world—each with its own intersection of social, cultural, formal, material, economic, and environmental concerns.

At the same time, the various students and faculty of Advanced V engaged in a shared discussion about the most interesting research, designs, practices, and ideas related to the built environment. They addressed the theme of “Architecture and Environment” and fortified the hypothesis that climate change is ground zero for a shared discussion about architecture’s engagement with the world. Responding to climate change requires attending not only to technical matters like energy consumption and carbon footprint, but also social and political issues, such as inequality and public policy. In this context, the Advanced V studios were framed as a unique and multifaceted opportunity to tackle climate change at the scale of the building and to address climate change through design.

1

Shape Evading Shapes

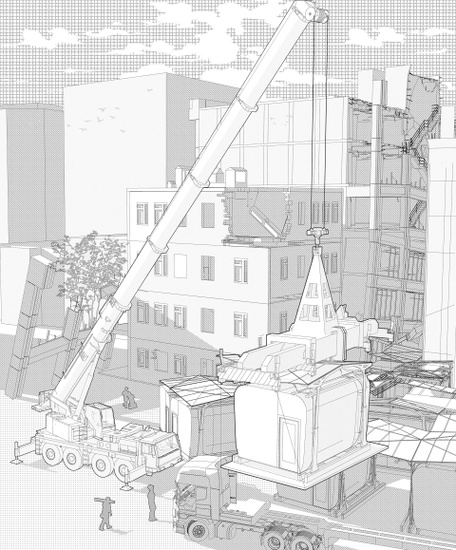

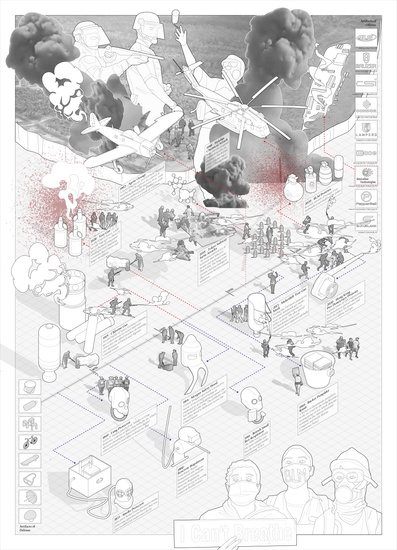

The clinic is a specific program with exacting needs; one of those needs is to both address the COVID-19 virus; another is to remain safe and resist becoming a transmitter of the virus. It must embrace the ill and defend against its own user - its own subject. It must also host several subjects; clinical actors / front line workers trained in medicine and patients and the general public if need be for broad testing. Working with the Re-Connecting Beirut studio led by Richard Plunz and Victor Body, the programming for the Shape Evading Shapes: A Rapidly Deployable Epidemiology Clinic studio comes from consultations with the World Health Organization. This studio takes the lead initially on the design and engineering aspects of the clinic – its parts, materials, components and performance concerns – and the Re-Connecting Beirut studio takes the lead on siting and urban design.

Students: Isabelle Bartenstein, Henry Han, Lihan Jin, Minjae Lee, Susan Lee, Fan Liu, Ran Ma, Yuanming Ma, Haoran Xu, Xiaoliang Ying, Chuyang Zhou

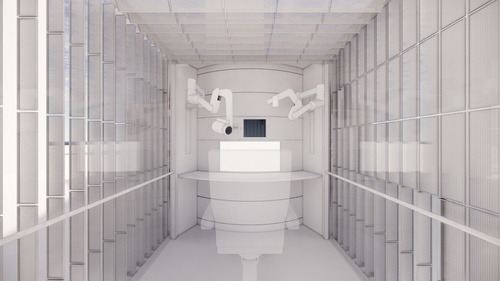

Empathy as Warmth - Rapidly Deployable Clinic

To think of clinics as a city’s social infrastructure, we must consider it a medical space for...

Transitional Clinic

The idea of medical gaze and the objectification of a patient’s body have become an unfair but...

Rapidly Deployable Clinic

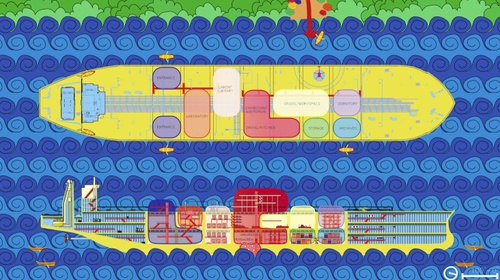

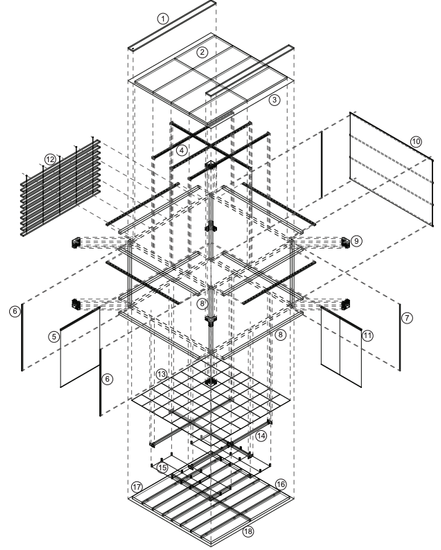

The design approach is to scale down a conventional clinic but maintain the minimum of space a...

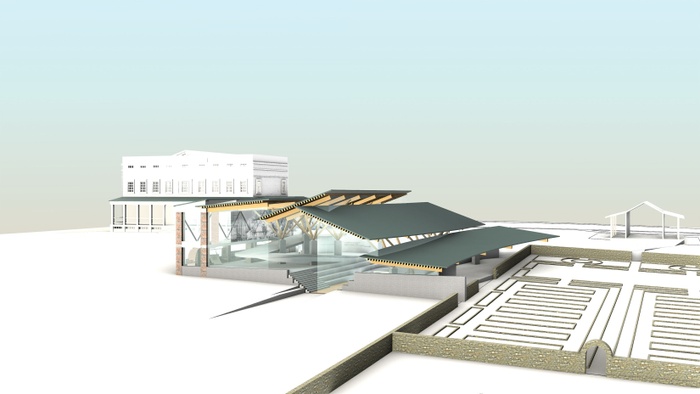

The design approach is to scale down a conventional clinic but maintain the minimum of space actually needed for an emergency. The architecture consists of chassis, pillar, steel, glass, and monocoque, which build up a negative-pressurized ward module. The same idea is applied to a test unit as well.

2

Climate Design Corps

The studio Climate Design Corps: Architecture for Environmental Justice explores the connected crises of public health, racial justice, and climate change through the lens of the Green New Deal in the United States, and it also considers the application of its findings to other places and countries. The studio is part of the Green New Deal Superstudio, which includes more than 80 studios from 50 universities. This collaboration with other schools allows it to exchange resources, ideas, and critiques with a diverse network. It also gives students the opportunity to share their work with a broad audience and contribute to a publication that aims to influence both policy-makers and practicing architects. The studio engages the Green New Deal Superstudio as a real-time experiment in collective thinking, collective design, and collective action.

Students: Angel Castillo, Chun-Wei Chen, Steven Corsello, Mike Kolodesh, Keon Hee Lee, Chengjie Li, Sixuan Liu, Genevieve Mateyko, Maria Perez Benavides, Frank Wang, Lewei Wang, Yu-Jun Yeh

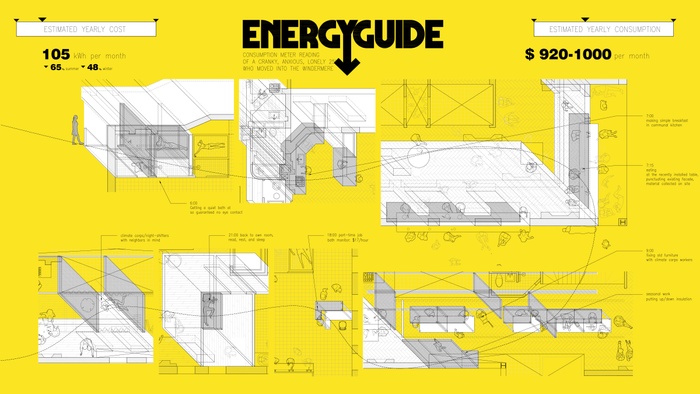

We are one living organism, connected. We have leased our knowledge of survival for convenience. This has conditioned us insensible to surroundings, potentially to physical and mental illness. Living with different degrees of friction, residents establish an autonomy of knowledge, time, and consumption. Constant Varies challenges the benchmark analyzing the energy performance of buildings. Taking care of the ever-changing building leads the residents to less energy-intensive activities, better health, and more resiliency towards uncertainty.

As we approach certain extinction by our own hands, it is time to consider how to make the best out of our predicament. Although actions have been taken to address the urgency of climate change such as the 2015 Paris Agreement, we are still on track to witness severe climate catastrophe. By 2100, Phoenix, Arizona is on course to become uninhabitable due to extreme heat and dust storms. At the same time, Arizona offers enough solar energy potential to power the continental United States. Coupled with millions of climate refugees that will pass through Phoenix by centuries end, we must imagine what actions we can take to assure that those most vulnerable will be protected. For these reasons, PHOENIX2100 imagines the transformation of Phoenix by a 22nd-century apocalyptic climate.

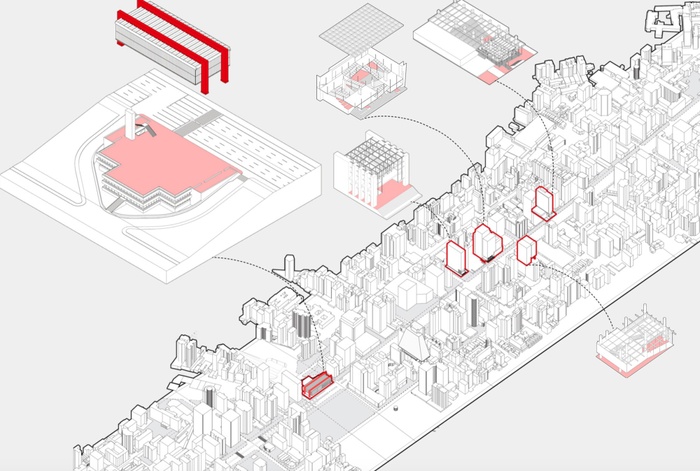

NYC Water and Social Infrastructure Rescaling Plan

This project aims at decarbonization at the scale of a city, creating green new jobs, and buil...

Green New City

New York City’s shortage of affordable housing has reached a crisis point in recent years and ...

The Carless Suburb

In an effort to reduce sprawl, I selected the Franklin Mills Mall in Northeast Philadelphia as...

The New American Suburbia is a framework proposed through the Green New Deal. Today, half of the country lives in a suburb and the average single-family household has a carbon footprint of 80 metric tons, while a household in Manhattan releases 32 tCO2e. The absurdly high carbon emissions are a product of the car-centric nature of the suburban layout as well as low permeability, large land occupancy, excess storage space, the culture of mass consumerism, the strip mall anchor, and the non-communal society. The idea of radically retrofitting suburbia through local interventions could set up the new (and sustainable) American Dream. By reinventing the way suburbs exist today, an increasingly economically diverse population with a multiplicity of ownership models, and with the capability of living in a 20-minute-walking shed could be a reality. The New American Suburbia will seek to eradicate the racist anti-Black laws that permitted suburbia to develop as a white phenomenon in postwar America. Since one of the main problems with suburbia today is the monotony and the replicated elements across the country, all suburbs should have interventions determined at the local level.

3

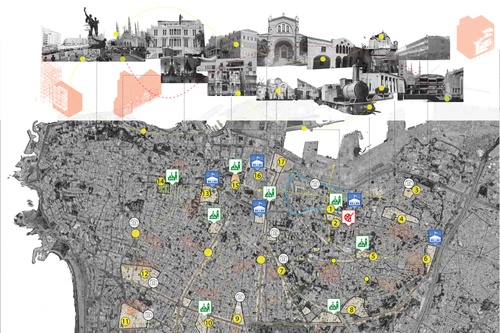

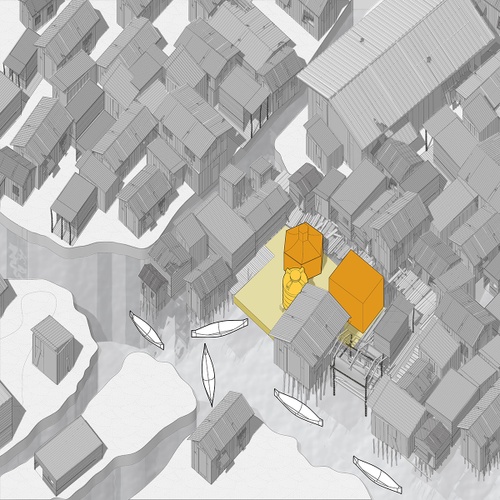

Re-connecting Beirut: In the Aftermath

In coordination with UN-Habitat, this studio addresses design issues related to rebuilding Beirut following the devastating explosions on August 4, 2020. Apart from a focus on rebuilding options for Gemmayze, the task is to connect this opportunity to rethinking the urban infrastructure of the city, to address many of the issues that were present before the present calamity, from infrastructural inadequacy to social disjunction. The studio is engaged with considerations of building strategies inclusive of the role of public space, but with broader considerations. The studio proposes a new kind of urban node deploying considerations that serves to inform the development of prototypes applicable elsewhere in the city and region, as well as other global cities facing similar challenges.

Students: Fahad Al Dughaish, Yasmin Ben Ltaifa, Ali El Sinbawy, Gabriela Franco, Liang He, Mia Mulic, Junyong Park, Aaron Sage, Cheng Shen, Ziang Tang, Xian Wu, Zihan Xiao

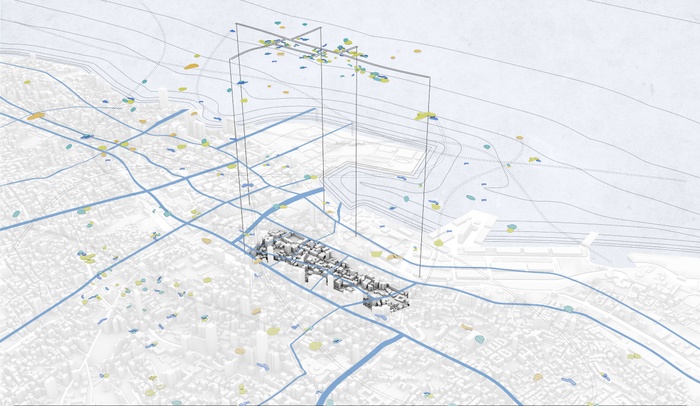

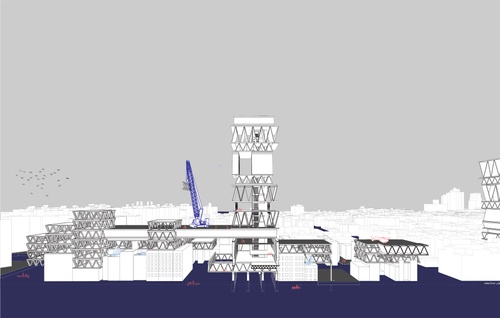

We are introducing a new form of urban micro-infrastructure that will serve as a programmatic host and generator for rebuilding the city, activating the currently untapped interstitial tissue of Beirut. Such interstices serve as a prototypical network for infrastructural reform, addressing the lack of essential services, facilitating economic recovery, promoting community engagement, and assuring embedded resilience.

Faced with a combination of the blast and pandemic, Beirutians suffer from inadequate access to basic resources such as water, energy, and food. We created “Seed,” a deployable architecture that not only acts as a host for activities but also provides resources needed to deploy them. The design gives self-sufficiency to the community through an intelligent system on which sustainable resiliency can be grown by the hands of the people.

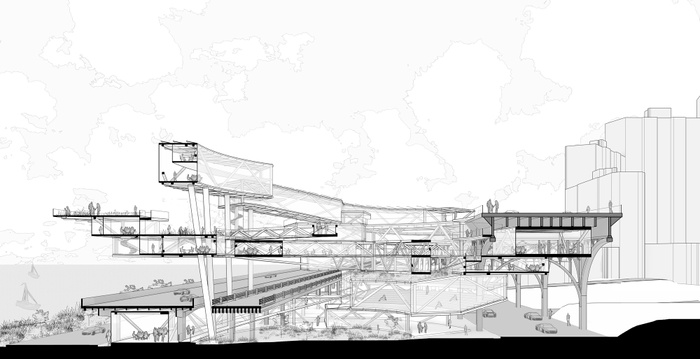

Transscalar Connectivity

A fragmented city with a rich history and diverse population – Beirut is in jeopardy of height...

Reconstructive Memory

As a response to the tragic blast and to reconnect Beirut globally, this strategy assumes reoc...

4

Climate Change Studio

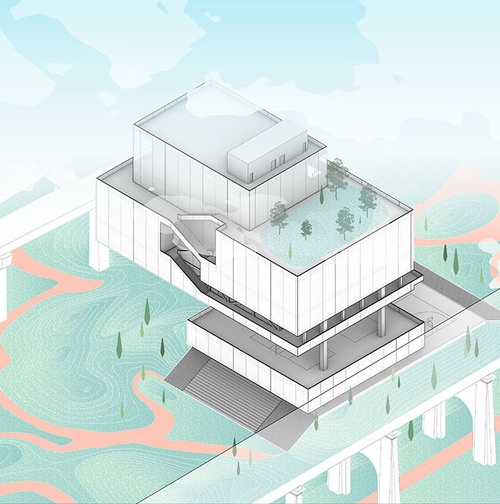

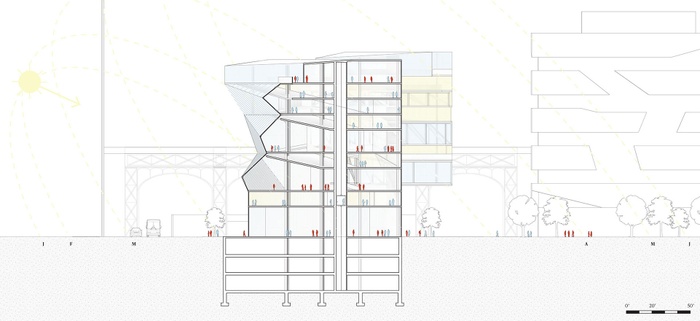

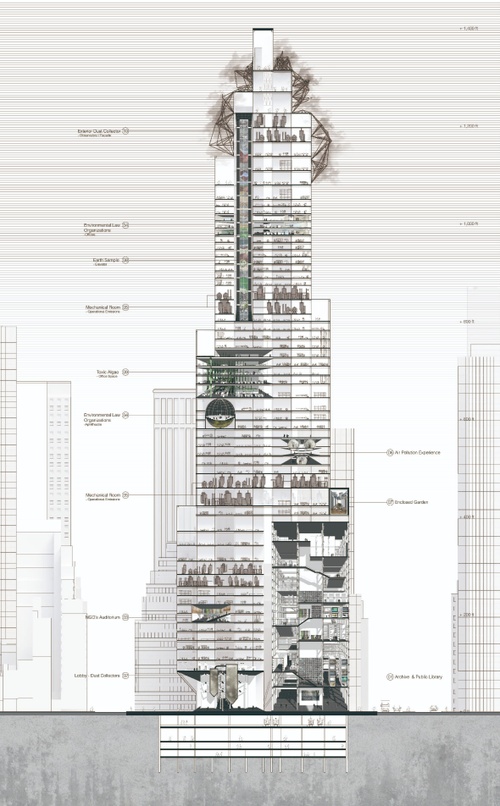

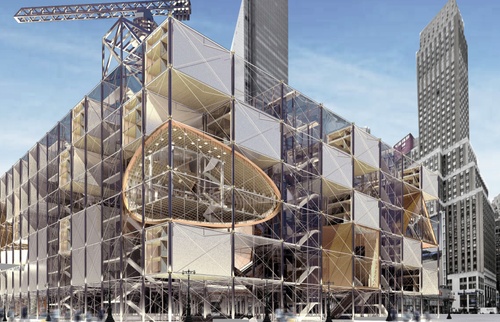

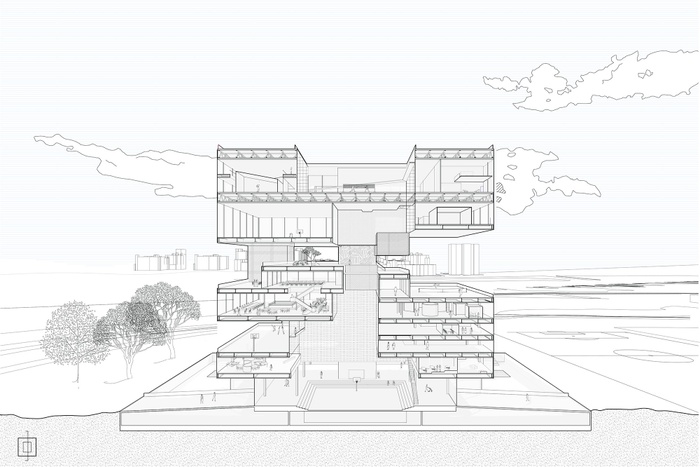

For this studio, students design a new Climate School for Columbia University. This studio speculates on ways in which the new Climate School will possess a new “architecture” in every sense of the term. The intention is to explore and reimagine that architecture, and its role in shaping knowledge now and in the future. The studio is primarily aimed at informed speculation and conceptual risk-taking at a moment in history that has already witnessed vast changes in the educational, institutional, social, political and physical landscape. The studio uses the frame of architecture to both re-conceptualize and re-invent a new School at the University. Some key questions for the studio are: What would be the form of this new school? What would be housed in the building(s)? How would these buildings perform to suit the new endeavors?

Students: Camille Jayne Esquivel, Rahul Gupta, Behruz Hairullaev, Keonyeong Jang, Nanjia Jiang, Spenser Krut, Marcell Sandor, Vera Savory, Charlotte Yu, Fengyi Zhang, Jingrou Zhao

The manifesto for this project is: First, Columbia University does not need another school. Second, the world does not need further evidence of climate change. Third, the University will provide space for the instruction of applied ethics. Climate will be the first theme adopted.

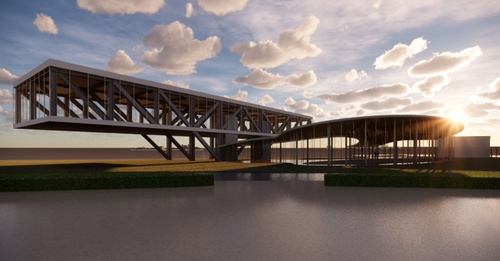

Amphibious Urbanism

Climate change impacts all disciplines equally. Confronting the climate crisis, the Climate Sc...

Climate School Center for Debate and Consensus

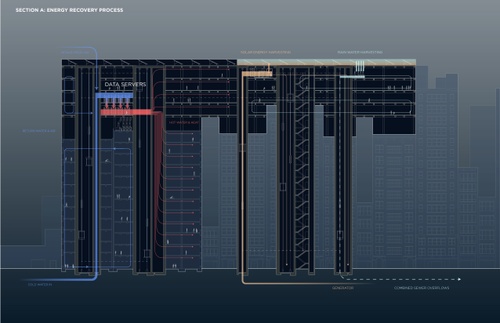

In consequence of recent pandemic situation, data-based spaces are being built on the net such...

Land, Water, Air Research Institute

The Land, Water, Air Research Institute Proposal confronts the boundary between human and natu...

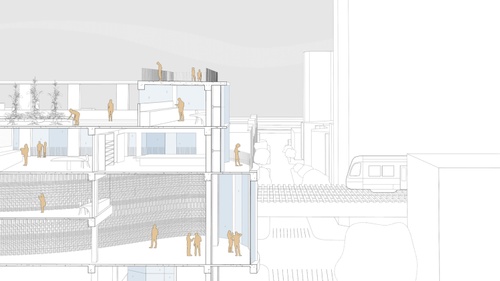

Divisions across the United States have widened and deepened over recent years. Such a polarized social and political climate has greatly hindered any efforts to advance climate policies, or facilitate any real change, especially amongst the local population. In order to transform our approach to change — for climate research and policies to have an impact on local and nationwide communities — the Climate School must be fully integrated and woven into the political and social landscape; operating as a center for both research and exchange.

The Climate School seeks to cultivate and maintain a close relationship with its local community. Transparency, communication and exchange will be key. Located at a crossroads in Manhattanville, The Climate School will operate as a bridge, elevating the subway, and connecting the two sites divided by Broadway.

Using the construct of the courtyard as a template for facilitating exchange and communication, the buildings on either side of the new building bridge over Broadway, will take the shape of two courtyards facing the new campus and residential buildings respectively, and generate more public space. The vertical circulation of the public around the elevated subway, through the building, and vice versa, will provide connection and transparency within the local community.

5

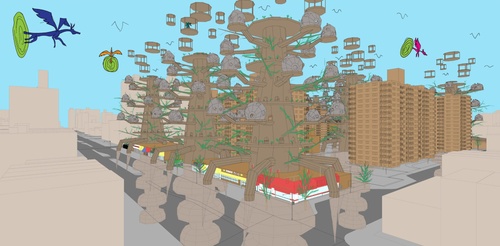

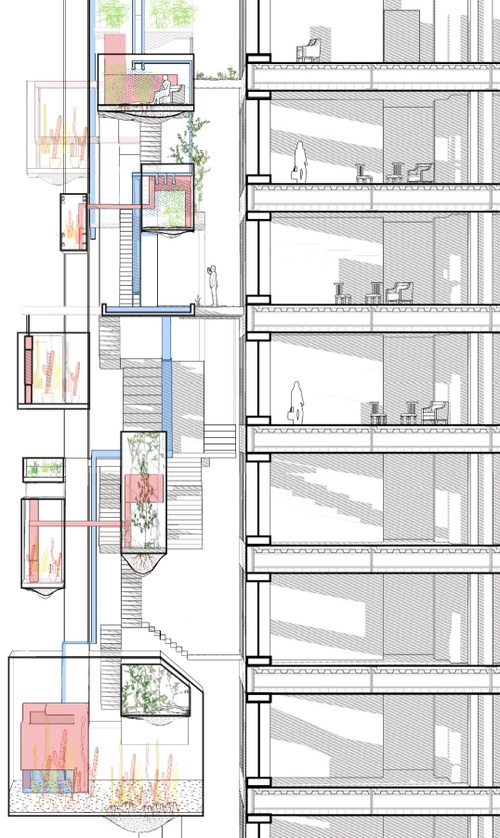

Formal/Informal

The studio Formal/Informal: Migrating Climates in the Immigrant City engages with immigrant communities to understand their everyday appropriations and adaptations to formal systems. Nearly half of the residents of Queens are foreign-born. Students learn from those who have migrated to the US, living in communities predominantly from Latin America, Asia, and the Caribbean. Studio sites are selected from the Jackson Heights, Elmhurst, and Corona neighborhoods. The design methodology includes case study research of non-Western architecture, urbanism, and visual forms of representation. The ambition is to design architecture or infrastructure that supports the front-line communities most at risk from the global health crisis, racial inequality, and the climate crisis.

Students: En-Ho Chan, Michelle Clara, Renee Gao, Liwei Guo, Abe Kung, Yuan Liu, Devansh Mehta, Yue Shi, Wanting Sun, Domenica Velasco

This project explores reciprocal relationships in affordable housing for senior Chinese immigrants in Flushing. An interface between the private and communal life of seniors, kitchens are paired with informal programs of gardening, small business activities, and childcare to serve as a social infrastructure that connects seniors with the larger community.

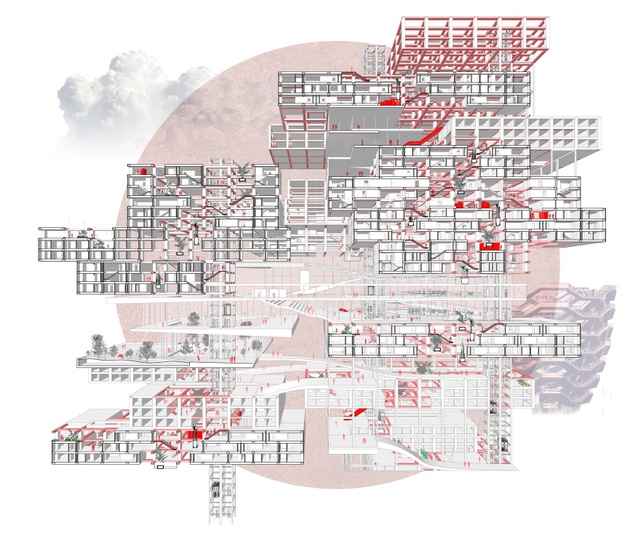

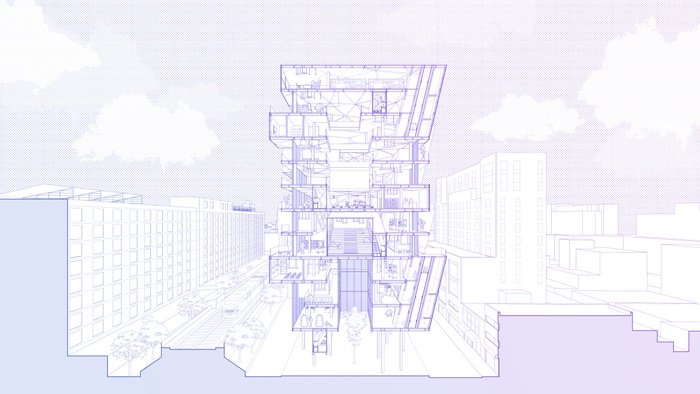

Balancing unpredictability and architectural authorship, the Open Tower reframes the conventional high-rise as a heterogeneous and non-hierarchical vertical city. The project democratizes the space, allowing its occupants to control informality and programming public agoras along the entirety of the tower, generating a new ground for immigrants displaced by climate change.

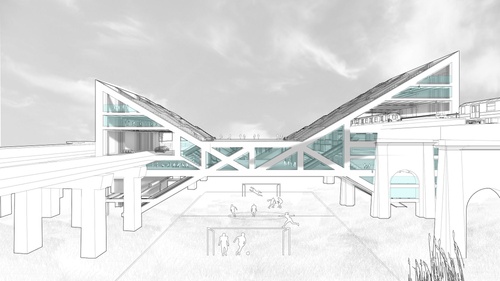

Due to the predicted sea-level rise in 2100, urban roadway transportation will be reduced. However, the current railway system in NYC will be less affected. Facing the potential climate crisis, this design of a community center transit system aims to reconnect the food supply chain and support Chinese immigrants with their business and everyday life. It aims to replace the long-distance food sources from Miami with new transportation systems, which will reconnect urban and regional community gardens and greenhouses through railways to form a food supply network. Greenhouses will be installed on the top of industrial buildings, factories, and shopping malls like auto repair shops and Macy’s outlets located next to railways. The proposed building supports the distribution of affordable cooked food to immigrant communities through the railway network. The starting point for this program is the design of a heterogeneous conveyor system—the anti-type in our program. Compared with the staircase and general circulation system, our informal conveyor system combines both function and transport.

6

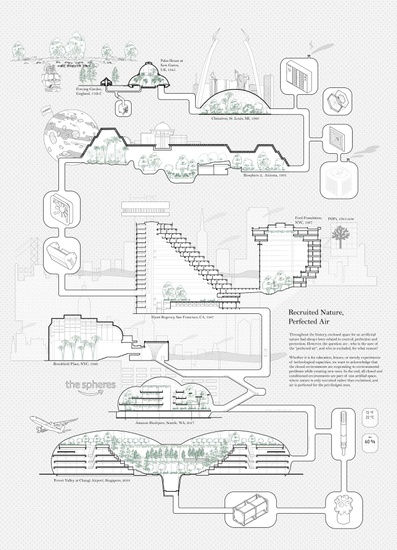

Plein Air

Acknowledging the complex material and socio-political performance of air, and the intersectional vulnerabilities and agencies compounded in the corporeality of air, this studio explores the architecture of “open” air, both figurative and literal. While often backgrounded and assumed as passively occupying undefined voids, air builds islands, of heat, and alleys, of cancerous fumes, duplicating the enclosures and lines produced elsewhere. Air forges “black snows” of sugar canes on the streets of Pahokee, FL, and morphs into tears, smoke, and mirrors, at the squares and borders across the globe. Innocuously connecting and incessantly shifting, the air is a lifeline and a weapon, and carefully delineated pods and shapey bubbles that might bring “the normal” back. Recognizing air as an elusive yet critical spatial medium, the studio engages air and the variegated materialities and ideologies of “plein/open air” as shared prompts for this semester’s exploration.

Students: Jinia Begum, Anirudh Chandar, Audrey Dandenault, Sarah Hejazin, Denise Jiang, SeokHyun Kim, Konstantina Marinaki, Ogheneochuko Okor, Angela Sun, Aleksandar Tomich, Brian Turner

The project introduces environmental remediation through the conversion of abandoned Distant Early Warning (DEW) line sites into a research and care system targeting Persistent Organic Pollutants concentrated in the Arctic atmosphere. Constructed to detect Cold War military threats, the network is deployed as a pollutant combatting matrix, committed to the well-being of Arctic peoples.

Marginalized communities often bear the burden of pollution inequity. Located in the South Bronx, the project looks to parks as a way to reclaim weaponized air for health education and asthma prevention in Mott Haven’s public school community. The proposal is an open air health campus combining educational and play spaces with breathing programs specifically targeting asthma, each which engage air through specific relationships with the human body, materiality, and movement.

Pneuma: Infrastructure for Air Accountability

The project brings public visibility to issues of air pollution affecting marginalized communi...

Who Owns the Air

This project challenges monetized corporate ownerships of air and their architecture, often im...

Smokes of Makoko

This project addresses poor air quality due to smoke and soot produced from a local sawmill an...

Flexible oases transform zones of historical disinvestment, resulting in racialized climates of deadly heat islands. They anchor into Baltimore’s vacant rowhouses and back alleys, recaptured as ecological, active, and infrastructural opportunities. Residents’ needs per block alter designs and programs, while shared materiality prioritizes air, light, circulation, and market appreciation.

Amazon Air® is a future Amazon facility that conflates different airs of the corporation - from truck pollution to warehouse dust, to the data center heat and artificially purified air of Amazon Spheres - into a single space. Challenging Amazon’s publicized “green” image, the project produces new atmospheric and programmatic conditions for production as well as resistance and allows life’s natural flow to hack it.

7

The Cosmosque

This studio The Cosmosque: Global Architecture of Benevolence investigates the reconceptualization of religious architecture, namely the mosque, as a means through which to engage social welfare programs—a critical undertaking at a time when, under the weight of the pandemic and other economic and environmental challenges, societies across the world are experiencing unprecedented levels of the lack of access to public services. Cosmosque proposes to shift away from the limited understanding of the architecture of the mosque that focuses on the construction of timeless monumental masterpieces and the celebration of a fictive ‘unity’ of Islamic architecture across time and geography. Instead, it aims to construct an alternate dynamic narrative of development, one that looks at the mosque as a hybrid and evolving building type, characterized by a rich historical tradition of constant negotiation, transformation, and alteration. Students map the physical evolution of each building and look at their contemporary conditions—studying them not as isolated objects, but as part of larger public, sacred territories that have been subjected to constant erosion. Operating at multiple scales on both sites concurrently and comparatively, the studio will aim to recast the typology of the mosque and its territory, as a complex with the capacity to engage the urgent social, economic, health and environmental challenges of its environs.

Students: Abdelrahman Albakri, Faisal Alohali, Chao Chang, Marie Christine Dimitri, Miranda Herpfer, Jasmine Jalinous, Xianghui Kong, Wanqi Sun

8

The Anti-Clearance Studio

The studio looks at processes of eviction, displacement, destruction, and social and ecological disarticulation as crucial phases in which architecture operates as a force for segregation, inequality, and uneven exposure to environmental vulnerability. Studio participants work with experts of different fields and communities affected by slum clearance and relocation to define architectural lines of action intended to undo, compensate, provide reparation, and exceed the structural and the particular damages site-making produced in particular locations in New York and around the world.

Students: Farah Alkhoury, Pabla Amigo, Ineajomaira Cuevas-Gonzalez, Man Hu, Kassandra Lee, Guoyu Liu, Mario Montesinos Marco, David Musa, Pietro Rosano, Magdalena Valdevenito, Ian Wach, Jerry Zhao

Project by Farah Alkhoury, Pabla Amigo, & Magdalena Valdevenito

Life Support Ecosystem is an Architecture and urban movement tested in the Lower East Side of Manhattan, in Cooper Square. Initially, the transition to collective ownership through a Land Trust System in Cooper Square took place in the 1990’s, following a series of events that threatened its inhabitants with slum clearance and displacement. The movement is driven by the idea that a society that functions under the basis of collective ownership requires its own spatial, material, and relational arrangements. Reflecting on the work of feminist writer Silvia Federici, the idea of “The Commons” has been adopted within the Life Support Ecosystem on the basis of cooperation and sharing among humans and non-humans. The model caters to those who have been excluded from real estate hegemony in Manhattan or unwilling to participate in it. Five main spatial transformations has been tested in Cooper Square to nurture the soil, grow food, collect and treat the water, compost and establish various degrees of sharing. (1) Food: The street, facade and roof are transformed into urban gardens, where 30% of the food used for neighbourhood consumption is harvested. The gardens are not just a source of food security but are also centers of social activity, knowledge production, cultural and intergenerational exchange. (2) Water : Rainwater is collected over the roof in tanks, and used for irrigating the roof garden and herbs. In addition, water used in showers and kitchens are treated to provide 60% of the water needed in the rest of the urban farm. The water is treated through a living ecosystem containing microscopic algae, fungi, bacteria and snails, fishes, shrubs, and trees that clean the water. (3). Compost : An ecosystem of compost modules span over the facade, where worms feed on leftover food, to provide minerals and nutrients for the soil and help plants grow. (4). Gradients of Sharing: The tenement housing typology is transformed to allow for walls to be folded, dismantled, moved and repurposed, to create a space that is flexible and fluid, catering for various household sizes. The system attempts to multiply the scales of familiarity and kinship through its spatial and material arrangements. The shops on the ground floor have also been transformed into a “neighbourhood closet” where personal belongings are shared and exchanged. (5). Culture: A society based on collective ownership requires its own form of culture and entertainment. A culture that challenges and confronts capitalism and consumption.

Manhattanville: Rebalancing Power to Create a Shared Neighborhood

In keeping with the studio’s focus on slum clearance, this project questions the narrative of ...

Property Wars

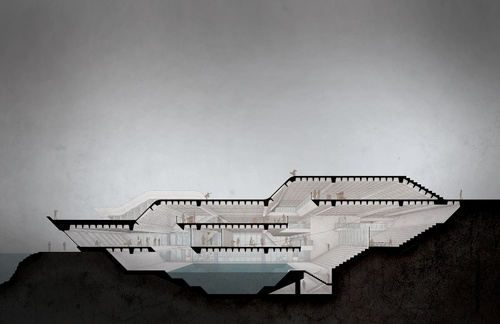

Property Wars is an afrofuturist narrative based on magical realism. It tells the story of Har...

The project is a visual tale telling a story of how three places in Rockaway Queens looks in a hundred years in a both utopian and dystopian way to bring up the question: How social, political and environmental impacts will affect the appearances of architecture and human.

Based on the history of Slum Clearance, sea level rise and the fact that the world is running out of sand, the story starts from a presumptive political decision: One day the government gives up the costly sand replenishment of Rockaway Beach and is convinced that the construction of seawall on dunes as infeasible. Instead, they allow the water to submerge the peninsula. However, rather than abandon the existed buildings and relocate, the local residents decide to stay and be adaptive to the new environment by leveraging man’s free will to reshape the social structure and biological culture of the site.

The goal of the adaptation is not to let the “architects”, a symbol of expertise, offer an “impeccable” solution to a specific client but to accumulate multidisciplinary knowledge to design imperfections and self-awakening to embrace the harsh nature and innate humanity. Only by establishing a symbiotic relationship between architecture, human and nature can we find a path toward truly resiliency and sustainability.

9

The Architecture of Activism

The performance of architecture is the crafting of space with intentionality. Architecture produces constructed objects and spaces which choreograph our interactions with our environments and one another. Architecture can play an activist role in combating social, economic, political and environmental disorders but it has been mostly spared from the conversation and action. The Architecture Of Activism studio aims to address this absence with the design and construction of architectural interventions to effectively mediate the interaction between an activism movement and the territory within which it operates.

Students: Nora Fadil, Jonathan Foy, Seonggeun Hur, Sungmin Kim, Emily Ruopp, Duo Zhang, Shuang Bi

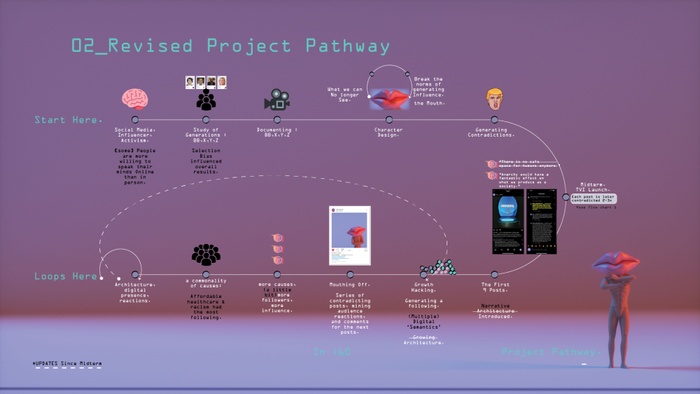

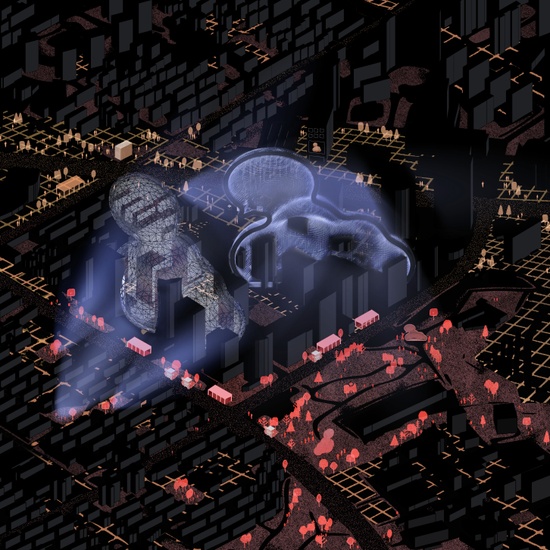

It begins with a radical social science experiment, recognizing social media’s power and how deeply intertwined it is with activism. By creating a Transgenerational Virtual Influencer, a series of contradictions are generated in hopes of finding a commonality of cause. By using the ‘wall’ as both a digital and architectural element, a series of narrative-driven walls stand as formal translations of cultural and political climates. Deeming social media the perfect propaganda machine, questioning whether architecture has more of a place within social media and activism.

Energy Tower in the Park creates an Architectural Activism that mitigates income inequality, climate vulnerability, and social vulnerability. Through building alterations and additions, it makes existing public housing become net-positive while also mobilizing a community to participate in the emerging sustainable economy but focusing on the most vulnerable populations first.

The number of investigative journalists in China becomes fewer and fewer. Clouduck, with its iconic shape, aims to help journalists spread their words freely and encourage the Chinese people to identify true and false information. The AR Clouduck also asks the question: “Does architecture need to be visible?”

10

Networks of Care: Design in Action

This studio joined forces with a multi-disciplinary group of designers, activists and scholars to ask about what a new politics of care might look like, how it might be realized, and what it can do when deployed as a toolkit for architecture and a mode of design. It provided students with spatial data and range of research and design methods to: diagnose and select sites which display underlying vulnerabilities, use their diagnoses to create a speculative toolkit for a care network, and then as proposal to put their design to work (into action). Students had access to a resource created by the Center for Spatial Research (CSR), in collaboration the Yale School of Public Health: Mapping a New Politics of Care.

Students: Shuang Bi, Ying Cheng, Nelson De Jesus Ubri, Lin Hou, Yuan Li, Digby Li, Jenifer Tello Sierra, Jiayue Xu, Sarah Zamler

The story starts in amazon warehouses during covid. Regardless of the surging death toll in the U.S, Amazon refused to shut down its facilities or acknowledge the full impact of COVID-19 on its workers; instead, it speeded up its operation, taking advantage of the economic desperation caused by COVID-19 to increase its market power and dominance. Based on Amazon’s exploitative business model, our project is a manual that guides its warehouse workers to take apart their job site and to rebuild their community with warehouse components. The manual consists of four chapters. The first chapter explains why the workers should say no to Amazon. We use GIS tools to explain Amazon’s warehouse site selection strategy. By overlapping the warehouse locations with the Social Vulnerability Index, we select three types of counties and examine Amazon’s impact on them. The second chapter describes the components of a warehouse, and the third chapter provides disassembly instructions. Lastly, we used the story of three counties to show how workers have rebuilt their communities after deconstructing their warehouses.

Staying Power is a toolkit of research and strategies aimed at fostering a network of care in response to evictions. The project analyzes systems of eviction both before and during the COVID-19 pandemic to understand how to empower tenants. A set of four interconnected proposals addresses each point of intervention.

11

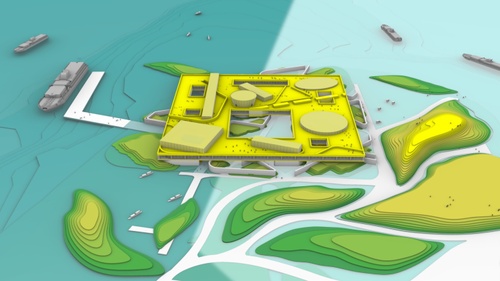

Waikīkī 2121

The studio Waikīkī 2121: An Academy for a Hawai‘i Future is part of a two year project in collaboration with Pacific Islander American architect, artist, and urban ecologist Sean Connelly, to radically re-imagine the urbanism of Honolulu, Hawai‘i, the most remote island in the world on the frontier of the COVID and climate crisis. The studio explores a trans-scalar and intersectional approach to interrupt existing US urbanism through a network of pedagogical sites (hālau) for indigenous knowledge (‘ike) at an architectural scale. The Academy for a Hawai‘i Future aims to empower indigenous Hawaiian knowledge, and the local ecologies of guardianship in a way that Mary Pukui described as “utilizing the resources of sustenance to a maximum.”

Students: Matthew Brubaker, Hao Chang, Greta Crispen, Charlotte Sie W Ho, Yao Hu, Timlok Li, Jiazhen Lin, Lu Liu, Adela Locsin, Jihae Park, Veeris Vanichtantikul, Florencia Yalale

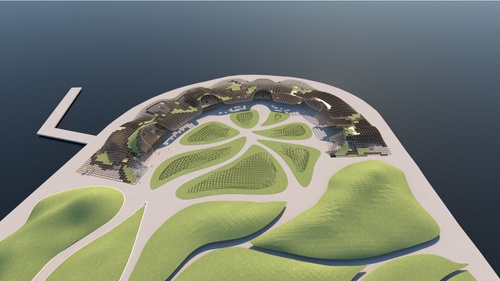

The Academy of Aquatic Regeneration positions non-human ecological actors, humans, and the built environment in a mutualism of ahu pua’a guardianship. This process includes reterritorializing the Ala Wai Small Boat Harbor as a marine estuary and coral reef over a 100 year period. This site will educate residents and visitors of Waikiki in processes of marine stewardship through a gradient of didactic spaces. By consequence of this reterritorization, the constructed ecology and coral network become key community actors as coastal protection against storm surge and a host of essential marine biodiversity. Coral reefs are the base of the watershed in an ahupua’a network, serving as a trustworthy indicator of upper, mid, and lower watershed health. Culturally, this ecological oasis is positioned as the genesis of Hawaiian culture, being referenced in the first 15 lines of the sacred 2,015 line creation chant, The Kumulipo. It is the site of transition from dry to wet and the birthplace of aquatic life and activity. As of 2020, the coral reef surrounding Waikiki has been deconstructed for imported leisure activities, the shoreline has been fragmented by private ownership, thereby worsening the already off-balance watershed health. This Academy creates new partnerships between existing actors at the site, following in the footsteps of a strong history of civic and environmental activism within the ahupua’a.

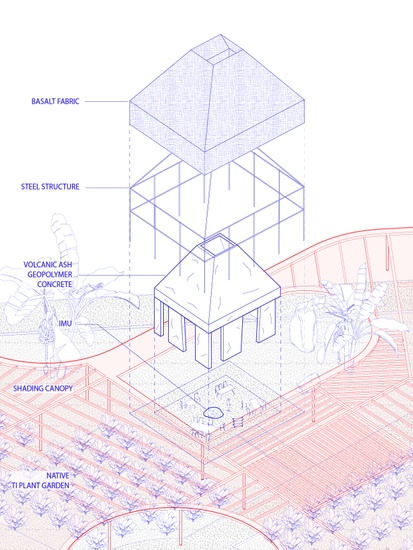

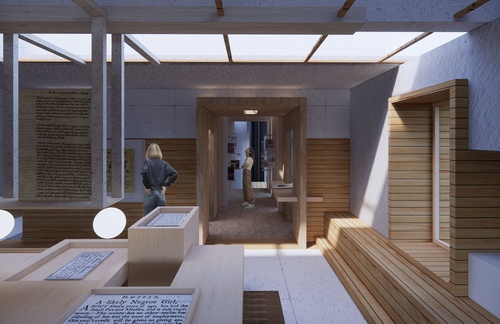

Through the study of Hawaii’s current and pre-colonial food systems, Academy of Hot Rocks examines the decentralized food network as a means to champion community through food education. The project focuses on the Imu, an underground earth oven native to Hawaii with its own expansive network of food, spirituality, and collective labor. This earth oven centered around slow cooking with hot basalt rocks, informs the basis of the material and tectonic language for the architecture. The Imu, much like the Ahupua’a system, relies on a network of exchanges, and the project proposes to expand this network at the urban scale. Food is a storytelling device to create agency, to connect us with people or distance ourselves from them. Food is pedagogical because of its embedded knowledge. The celebration of the Hawaiin Imu as a network of storytelling and exchange hopes to serve as one component in the restorative network laid out across other sites in this studio.

Academy of Land

The Academy of Land seeks a new form of academy adapted to hybrid postcolonial futures where n...

Academy of Canoe / Koa

Canoe is an indigenous culture in Hawaii which reflects Hawaiian spirit on how to look at the ...

Over Kalia Loko I'a - the largest aquaculture system of the fishpond in Waikiki, the reclamation of Waikiki began here when the U.S. Army Corps started draining this land to build Fort DeRussy in 1909. It became a symbol of colonization and militarization, leaving native Hawaiian with the scars of environmental alterations, historical trauma, and cultural wounding. Accordingly, ‘The Academy of Healing and Resolution’ is established as the sanctuary to recover the native land and people from all those traumas. In parallel, it will become a pedagogical site where visitors can learn the indigenous practices of healing. With the highest intention to reestablish social justice for the native Hawaiian, the academy is designed as a space for collective gathering and social interaction. It will be a gateway to link people from the upland(Makau) and the plain(Kula) to the sea(Makai), and a bridge to connect people from Waikiki city to the fishponds. This project will be a place where the community can keep a memory of the past embracing their culture and history, exist in the present situating themselves as a part of modern society, while being free to live with health, determination, and resolution into the future.

12

Radical

Re-construction

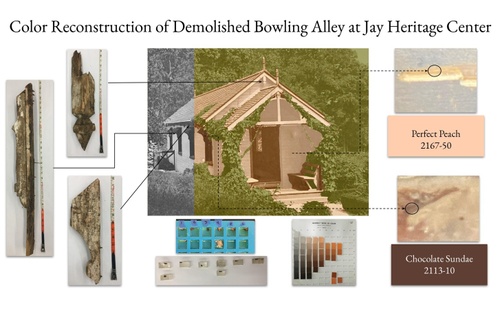

This joint architecture and historic preservation studio Radical Re-construction: Materializing Social Justice at the Estate of John Jay, a Founder of American Democracy proposes the design of a new interpretative education center, and a series of reconstructions of missing buildings associated with under-represented narratives at the John Jay Heritage site, engaging the crucial need today to expose and materialize the space of political, psychological, and social exclusions and inclusions at the root of the foundations of American democracy. The architectural and preservation question of the studio is how to materialize the matter of these entangled lives in their complex historical and current interrelations — how to reconstruct what is hidden or under-represented. Reconstruction has been traditionally understood as rebuilding a building “as it was, where it was.” What this studio proposes is that all construction is a form of re-construction, a reworking of pre-existing forms of social and political constructs. Today so many of those political pre-existing constructs need re-construction, as much now as during the period of American history right after the Civil War that was called the Reconstruction Era, the failures of which to redress racial inequalities then we are still living with today.

Students: Zachary Bundy, Hong Yu Thomas Chiu, Chiun Heng Chou, Tianyuan Deng, Abhinav Gupta, Marisa Kefalidis, Yuedong Lin, Yanan Zhou

apparatus of projection

The Apparatus of Projection - A Reconstruction of John Jay and New York Manumission Society’s ...

Outside-In

As the visitor center of John Jay Heritage Center and another entrance of John Jay estate, the...

Walking Inside The Wall: Illuminating the Hidden History of Slaves

This project proposes the design of a new interpretative education center at the John Jay Heri...

By reconfiguring one of the most identifiable elements, roof, of the houses on the site, and turning it into a series of spaces that holds both the exhibitions of different themes as well as various programs, the project tells a story associated with the Jay Heritage Center of the slave history in New York and the individuals who had once lived on the property and made an effort to push for the accomplishment of the Manumission.

13

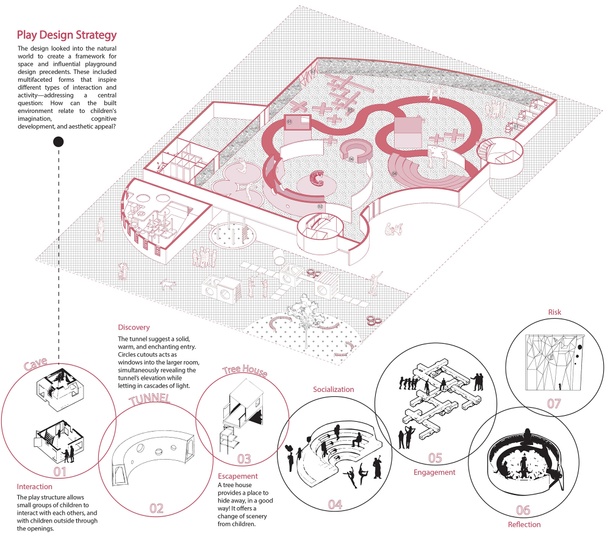

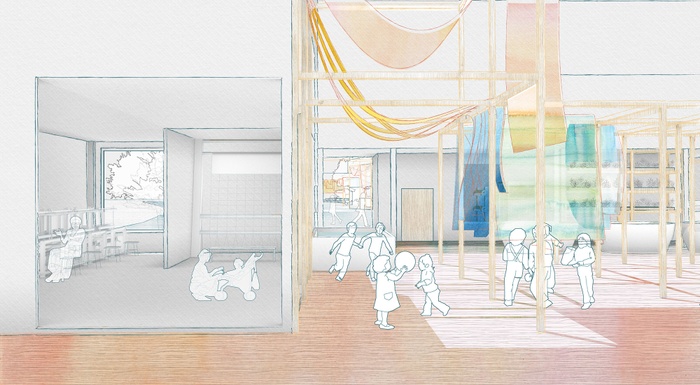

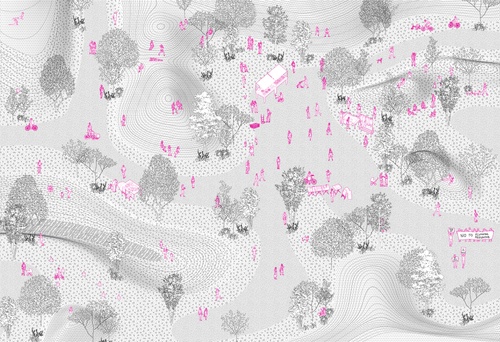

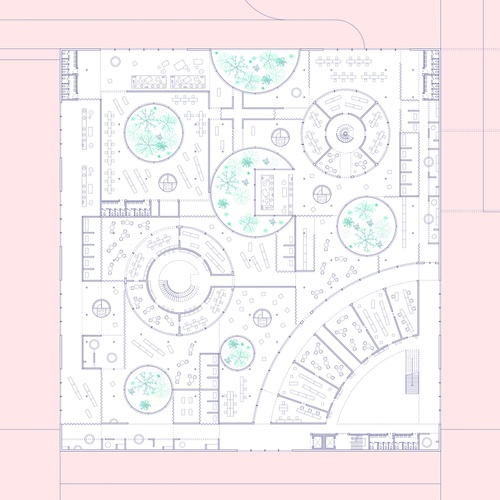

A City for Child Care

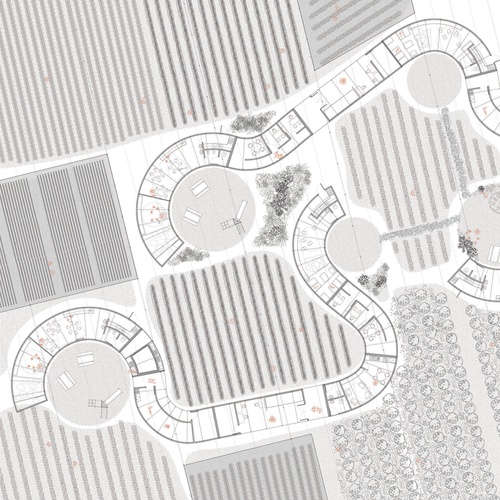

The studio examines how child care is entangled with the politics of gender, race, and labor. Addressing child care as both an architectural and social issue, the studio addresses a space of care holistically, imagining how a new child care center could support three intertwined populations: children, parental figures, and care workers. Working at the scales of both architecture and urban design, students explore the design of child care from the material realization of an individual building to the larger scale of its surrounding urban context. Students imagine a child care center at the heart of a Community Land Trust - a form of land stewardship that supports long-term affordability and counters gentrification - along the Flushing Creek in Queens. The studio involves a close collaboration with the members of the Fed Up Coalition.

Students: Refan Abed, Camille Brustlein, Mark-Henry Decrausaz, Sumi Li, Tung Nguyen, Xinyi Qu, Lauren Scott, Ruijing Sun, Liza Tedeschi, Yueyang Wang, Eunjin Yoo

The project attempts to create an architecture that provides residence care, embraces their abilities, acknowledges their differences, and this is by providing job opportunities, affordable housing options, and childcare facilities. It addresses central questions that resonate in fundamental ways with life in the city today: “How can architecture offer access for a healthful and equal lifestyle considering children, working parents, and care workers?” And “How can architecture organize different scales of community engagement over different demographics?” Besides, nature is by far the best learning ground for children; It was essential to consciously bring in some of its intriguing aspects into the childcare facility’s design thinking; to encourage children to move in countless ways. That may be one of the most fundamental methods in fully exploring their physical and cognitive abilities.

A design leverages fabric production as a mechanism for fostering a community in the realm of cultural identity, economic benefit, and environmental sustainability with various programs including a childcare center, a community center, factories, farms, and so on. It is mainly tailored for Chinese and overall Asian residents and their children as the future of the land but welcomes all races.

Landscape of Care

This project aims to provide a network of support to the existing informal systems of care in ...

Public Luxury

Public luxury ties together formats of public wellness using water as a medium for care to ser...

The Urban Arcade

The design is aiming to extend the community while providing an organizational arcade structur...

Playscape

The project lends itself to the idea of ‘Playscape’, where nature intertwines with the artific...

Productivity at Play

This proposal embeds, overlaps, and intertwines productive agricultural and reproductive child...

Architecturalized Landscape

This architecturalized landscape provides safe and dynamic spaces to support the health and we...

Urban Playscape

My design proposal is to design an urban playscape that has buildings as objects within it. At...

14

Streets of Pandemonium

For this studio, student groups investigate four topics: the Avenue of Climate Change; the Street of the Pandemic; the Avenue of Mobility; and the Street of Justice. The studio is interested in reversing expectations, in exploring what no one considers the proper approach. It likes questioning the dictionary of received ideas and playing devil’s advocate. It likes addressing problems upside-down and the wrong way around. It believes creativity often begins with the unacceptable. The strategies are to propose an unusual hypothesis, whether social, programmatic or technological, and see if it can lead to an unexpected architecture or urbanism, in order to demonstrate the validity of the original hypothesis. Or alternatively, to define an unusual architectural or urban hypothesis, and then investigate whether it could help resolve a social, programmatic or technological issue.

Students: Sarah Abouelkhair, Jun Ito, Shan Li, Yi Liu, Hemila Rastegar-Aria, Ziyi Wang, Chia Jung Wen, Ye Xu, Yuexi Xu, Tianyu Yang, Zoe Zhai, Kiwi Zhu

This project confronts mobility and stillness within a street experience, implementing foreseeable technologies and different types of human-nature interaction, while exploring new possibilities of social occasion and activities. It suggests a paradox in which the mobility of efficiency and the stillness of serenity coexist within the street experience.

The Pandemic Street: Pandemic Home

This project addresses two scenarios: present- and post-pandemic. Humanity and socializing are...

The Street of Justice: Coup d'Social

We designed an intervention that worked in reverse to provide equity, a space for women, the n...

15

Productive Uncertainty

This studio Productive Uncertainty: Indeterminacy, Impermanence and the Architectural Imagination asks how the material conditions of architecture might engage the increasing volatility that characterizes our collective relationship to emergent environmental, climatological, biological, political, and social conditions. Extending beyond the immediate crises, it seeks to interrogate architecture’s intersection with notions of adaptability, transience, and transformation. It asks: How do we navigate the impossibility of future-proofing on the one hand and the inevitability of obsolescence on the other? How do we avoid the trap of designing for the last crisis while allowing for the emergence of the unforeseeable? What would it mean to understand impermanence and instability as a site in which fundamental conditions of architecture, notions of structure, inhabitation, program, and environmental control could be challenged, reconfigured and rethought in new and productive ways? What if architecture’s inherent slowness could be the very countermeasure required in a world that has always been essentially unstable and precarious?

Students: Rasam Aminzadeh, Yuan Chen, Kshama Daftary, Chenxi Dong, Jishan Duan, Yi Jiang, Camille Lanier, Xinran Shen, Yilun Sun, Tianheng Xu, Chen Yang, Tian Yao

This project proposes a replicable system of architecture that attempts to explore the relationship between architecture and recycled materials, especially construction and demolition materials, in response to the overall theme of productive uncertainty. This project is used as a test site to be implemented elsewhere and as an opportunity to create a recycling complex for communities.

Remedy Labs

Remedy Labs is an infrastructure that withstands toxic controversies in Newton Creek and attra...

Migrate the City

This project proposes adding a valve on the threshold of the city to reduce the uncertainty of...

Membrane Sucker

What is a quarantine of nature and society? Building envelopes act as a method and media to s...

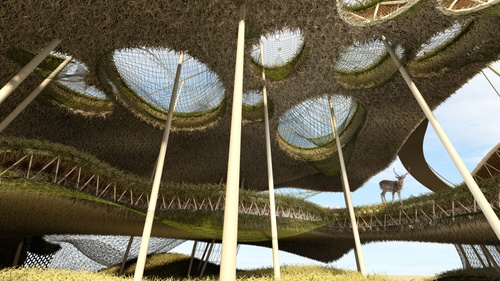

Terrapolis

The project answered the brief of uncertainty by creating a habitat where all species (human, ...

Aquatic 2100

In the 2100s, Alphabet City‘s street level will be submerged in water. Residents in this area ...

This project focuses on the uncertainties of Broadway and the theatre industry, particularly in regards to social precarity. The two sites include Times Square and the Lincoln Center.

16

Open Work

This studio collectively addresses two buildings in South America that intersected the debate on open-endedness, namely: the MASP (1957-1968) in São Paulo by Lina Bo Bardi, and the UNCTAD III (1971-1972) in Santiago by José Covacevic, Juan Echeñique, Hugo Gaggero, Sergio González, and José Medina. The studio brief is to join a team, and either double the surface, or halve the program of the buildings. The studio question is to design in conversation with, and take position on, a building and the arguments it advanced, and to tackle a longstanding question within the field, again, half a century later.

Students: Tamim Aljefri, Oliver Bradley, Alice Fang, Begum Karaoglu, Chengliang Li, Patrick Lin, Jinxia Lou, Joel McCullough, Zhijian Sun, Kai Wang

Our project extends beyond the site and reuses what is left to create a new cultural institution in conversation with UNCTAD’s history.

“Today we turn our eyes to Lina Bo Bardi, a most underrated architect in South America and the pioneer of Brazilian modern architecture who advocated open-ended works.”

17

Protocols of Care: Bodies of Assembly

This studio examines radical care practices in art and performance to imagine new protocols for an architecture of care. The studio evolves through two research projects and a design project sited in Lower Manhattan. To begin the studio, Mobile Assemblies maps and animates the time/space of recent BLM protests that erupted across NYC to better understand the dynamic urban/architectural choreography collective assembly. Through notating kinaesthetic and urban movement, the studio also explores the cadences of an individual body as it walks through a city by recording via video how the pandemic has reconfigured everyday interactions. These explorations and documentations of collective assembly and the body will contribute to the design of “protocols of care.” These new architectural/urban choreographies are used to design spaces of assembly and care for the Danspace Project. This experimental dance initiative is based at St. Mark’s-in-the-Bowery Church in the East Village of New York City, which, with its surrounding grounds, serves as the project’s site. Working relationally between body, city, planet, the project for Bodies of Assembly will be to create spaces for the caretaking of humans, non-human species and things, and for public assembly on the site of St. Mark’s-in-the-Bowery.

Students: Ashley Esparza, Melita Kantai, Mariami Maghlakelidze, Camila Nuñez, Urechi Oguguo, Luis Pizano, Skylar Royal, Taylor Urbshott, Reem Yassin

A historical walk and performance from Wall Street to St. Marks Church in the Bowery inspired by historically significant locations, the history of slavery in the Lower East Side, and modern protesting methods. The walk tells the stories and history through permanent markers and incorporate three additional sites along the route that highlight and deploy different aspects of this history through listening, sharing knowledge, rest, and amplification.

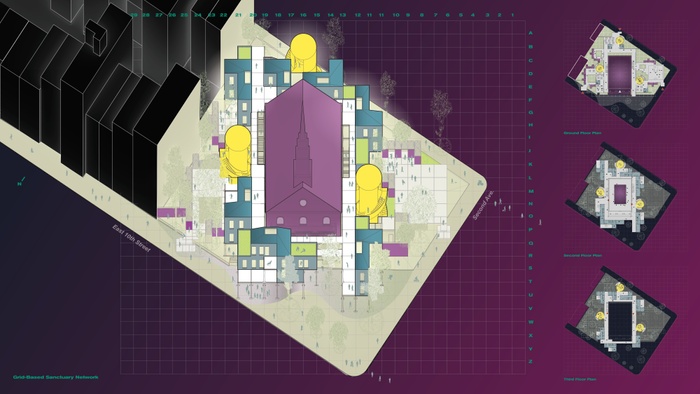

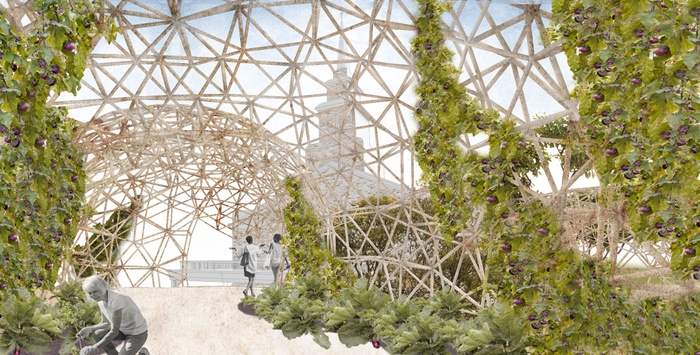

Increasing disinvestment in the public sector threatens the welfare of vulnerable communities. In particular, climate refugees and asylum seekers are left to experience immeasurable risk, for their livelihood is compromised by the loss of housing services and legal assistance. In the East Village, St. Mark’s Church functions as a unique community space, having served as a primary anchor for the artistic, political and revolutionary movements of the neighborhood in the 20th Century. The proposal for a Sanctuary Network at St. Mark’s generates a community-minded platform for recent migrants, which extends the protective infrastructure of church, site, and community through a series of user-oriented program tiers. Each tier is coordinated around a set of primary services, including temporary housing, collective kitchens for resident and community use, and service “"pods”“ that house legal counsel, advocacy, and small-scale market spaces. Integral to this system is a circuit of insulated pipes that connect to on-site plumbing and heating, allowing St. Mark’s to feed the program tiers. Project materials emphasize minimal carbon footprint, including Compressed-Laminated-Timber construction and off-the-shelf steel scaffolding. When unoccupied by the sanctuary users, the stackable, vertically-connected housing units can be shared by artists from Danspace, the site’s primary host institution.

Healing Spaces

The project, titled Healing Spaces, is an investigation on how the practice of care in archite...

Landscape of Grief and Care

Our project looks to the performance of religious, spiritual, and cultural grief rituals as an...

Networked Protest Protection and Spatialized Rehabilitation

With the current paradigm of shared media, the definition of witness has been restructured awa...

Our project breaks down the garden to an understanding of its essence—not as a noun as it is popularly understood, describing a physical place, but as a verb defining exchange of care at all scales. Using St. Mark’s Church-in-the-Bowery as a point of contact, this project focuses on identifying and tending to these areas in the city which have systematically been uncared-for. Considering the history and location of the church grounds, this project proposes a range of garden prototypes for vast networks of care— for the gardener, and the performance of gardening; for rest, rejuvenation, and gathering; for the garden, and the medicinal herbs and vegetables that the space provides with the possibility of growth; for the uncared-for and historically neglected communities in East Village, whose spaces these gardens will be adapted to in order to exchange breath, nutrition, and care. The order of the garden is a reclamation of the urban space. It is a disruption of the formal systems that make up the orders of the city as we know it. It is a network that prioritizes the safety, wellbeing, and growth of all participants— human, non-human, and thing alike.

18

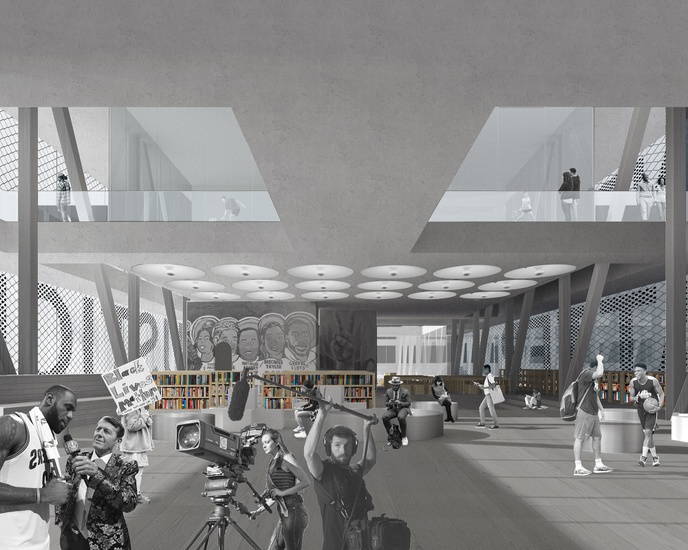

A Center for Sports Diplomacy

As we enter the uncharted future post-climate change, post-COVID, and either post-Trump or post-Democracy, we have the opportunity to define new typologies that can better address the contemporary condition, both in the US and around the world. For this studio, students interrogate, investigate, envision and create a new institutional typology: the Center for Sports Diplomacy, which acknowledges the increasingly important role that sports plays in advocating social and racial justice, reform and the advancement of a progressive view of society, both nationally and internationally. A combination of diplomatic mission, media zone, wellness center, production studio, training facility and community hub, the studio together works to define this new typology and give it resonance.

Students: Alina Abouelenin, Benjamin Akhavan, Erin Biediger, Melissa Chervin, Cong Diao, Jindian Fu, Cameron Fullmer, Jacob Gilbert, Hao-Yeh Lu, Tristan Schendel, Zhongen Xu, Elie Zeinoun

Climate change is starting to impact every aspect of sports. Designing a sports center for climate action in Randall’s Island will raise the community awareness of climate change and find possible solutions through collective action. The building will serve as a gathering, training, and educational space for people with interest in sports.

The Embassy of X explores the intersection between sports, politics and architecture, blurring the boundaries between all of them. It uses the sports field as the extension of the political deliberation room and vice versa, this essential concept allowing for unique outdoor and indoor spatial moments to occur. At its core, the building challenges the question: Where does sports end and politics begin?

Transportation Arena for the Public

The Transportation Arena for the Public is a center for sports diplomacy on Randall’s Island. ...

Integrated Sports and Spectator Center

This project is inspired by a thorough research on the relationship between play and spectator...

Water Fun Palace

The pandemic has changed everything. People are suffering, mental health issues are increasing...

The Center for Women’s Sports and Advocacy

The Center for Women’s Sports and Advocacy is an inclusive facility that aims to promote gende...

Concurrent Center for Democracy

Democracy is a word derived from the term politics but it can also be used in the context of s...

The Center for Sports Diplomacy aims to be both a space for recreation, and a place where sports spectators are forced to interact with and consume information about social and political issues through a promenade experience.