Why Publish? Reframing the Stakes of Student Publications

Event Description

Introduction

Office of Publications Presentation On

Guest Presentation On

Office of Publications Presentation On

Guest Presentation On

Office of Publications Presentation On

Guest Presentation On

Office of Publications Presentation On

Guest Presentation On

Resources From

1

2

3

4

5

6

Logistical Information On

00

Event Description

Introductions by the Office of Publications:

Isabelle Kirkham-Lewitt, Director

Joanna Joseph, Assistant Director

Meriam Soltan, Assistant Editor

Isabelle A. Tan, Assistant Editor

Presentations by:

Laura Coombs, Graphic designer

Nicholas Korody, Writer, editor, designer

Jacob R. Moore, Curator, critic, editor

Grace Sparapani, Writer, editor

This event was presented in a hybrid in-person and virtual format. The workshop consists of two sessions, one in summer and one in fall:

Summer, Session 1—Building an Editorial Practice

Tuesday, July 26, 2022

5:30pm-7:30pm

Ware Lounge, Avery Hall

Session 1 introduced students to a diverse range of possible positions, projects, and methodologies for realizing a publication from start to finish with the aim of collectively building and sharing resources.

Fall, Session 2—Sharing Proposals

Friday, October 14, 2022

12pm-2pm

Room 209, Fayerweather Hall

Session 2 will invite students to present and receive feedback on their publication proposals and to engage others in the structure and ambitions of their publications.

Introduction

Why Publish?

IKL - Isabelle Kirkham-Lewitt

JJ - Joanna Joseph

IKL: Hi everyone, thanks so much for joining us. My name is Isabelle Kirkham-Lewitt, I’m the director of the Office of Publications: ¼ of the office, alongside my colleagues Joanna Joseph, Meriam Soltan, and Isabelle Tan. This is the first time our office is speaking directly to many of you about student publications and we’re thrilled to be able to share the work we do in this context and to be in conversation with you and your ideas down the line. We also have some wonderful people here tonight––some longtime and new collaborators—so a big thank you to Nick, Laura, Grace, and Jacob for taking the time and space to think with us. In fact, more than collaborators, they are our teachers. And I’m so super excited to learn and hear from people we work with everyday in this different capacity. But before jumping in, we want to briefly introduce what it is we’re doing here:

By being here tonight, we think it is safe to assume that everyone is, at least in part, invested in the work of publishing—and if not invested, then in some way aware of the kind of power and possibilities opened up by printed work. And it is because of this common ground, this investment and dedication, that we want to start from a place of ambivalence, to interrogate why it is that one should even publish in the first place, especially in the context of a school of design. To ask “Why Publish?” is not necessarily to deter you—or us for that matter—from pursuing publication projects, rather it is to insist that uncertainty is a productive space to sit in and with at every point in the process. We’re going to be asking ourselves this question over and over again tonight. Why? The hope being not to answer it but to remain endlessly curious about the work we do and have done.

JJ: Thanks for kicking things off Isabelle! My name is Joanna Joseph and I’m the Assistant Director of the Office of Publications. As we’ve stated, this workshop is rooted in the belief that why and how we publish is just as important as what we publish, and we hope with this workshop to provide you with a set of tools and resources to guide thoughtful, intentional editorial practice. Much like publishing, to design is to communicate, to find and make community. Publishing evolves design practice, and practice provokes further thought, further questions. If the university is the place where how we design can be questioned, expanded, refined, experimented with, writing and publishing can be powerful tools in this action.

Rather than formal introductions to our office––Isabelle and I, alongside Meriam and Isabelle Tan, are going to take you through a few of our publishing projects as a way of modeling the questions and considerations that have both generated and have been generated by our work. The aim is not to demonstrate that these methods are by any means the “right” or only way of producing a publication—they are certainly not! But by revisiting each project, we hope to re-meet and reframe the “why’s” and the “how’s” of the work for ourselves too.

IKL: We also want to insist that, by being here, we all start to consider ourselves as editors. Whether that’s helping structure ideas, designing them across the page, reconfiguring them textually, or in the margins, the work of editing always requires us to think both within and beyond whatever it is we’re working on. Writing, research, and publications are products of design themselves, and in turn are capable of designing environments, attitudes, conditions. As with the fabric of the built environment, publications cannot be separated from the conditions that produce them, their contributors, contents, materials, modes of circulation carry particular motivations and biases. But in becoming editors, we also want to reformulate what this position means, to decenter notions of hierarchy or expertise that are often assumed with editorial work (and coincidentally or not, often with architectural work…). So, again, our wonderful collaborators here tonight are testament to the truly collective nature of publishing, and, I think, each in their own way, show us how we can continue to frame editorial practice as an architectural practice and vice versa. (I actually think most if not all are either graduates of GSAPP, or adjacent to the school and to architecture.).

JJ: Today’s session is part one of a two-part workshop. Today we will be modeling guidelines and gathering resources for building an editorial practice. We will explore some of our office’s projects in depth, and we’ve asked the participants to explore a particular methodology through both their own work, and through the work of others.

In October, students will be invited back to workshop their own publication ideas and proposals with us in a more informal, yet hands-on session.

We know that a lot of you are also seeking more logistical information on the actual nuts and bolts of organizing a publication while you are a student at GSAPP. We want to say up front that the Office of Publications does not actually facilitate students’ printed work, rather these initiatives are supported by the Student Council. That being said, we will be providing you, both later today and on the GSAPP website, with a consolidated guide on how to organize a student publication, and what production resources are available to you. We will also hopefully have some time for some student questions after the presentations, so please hang on to your questions as they arise, or feel free to write them in the zoom chat.

So without further ado, I’m going to hand the mic off to Isabelle!

Office of Publications Presentation On

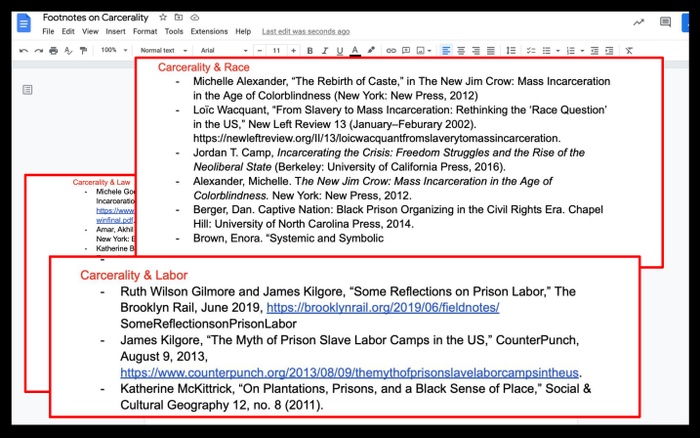

Paths to Prison: On the Architectures of Carcerality

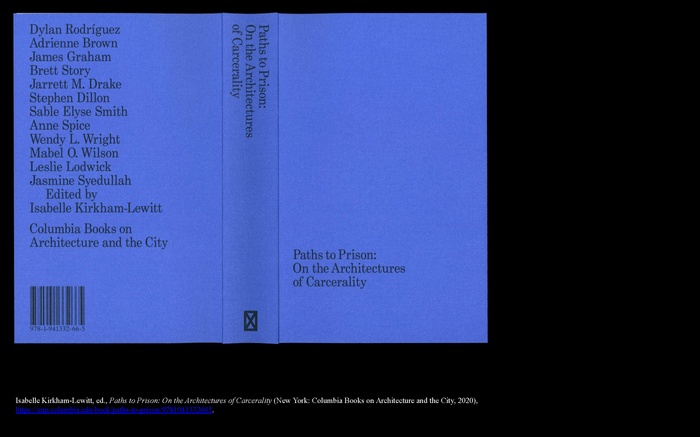

Isabelle Kirkham-Lewitt, ed., Paths to Prison: On the Architectures of Carcerality (New York: Columbia Books on Architecture and the City, 2020), link.

I’m going to kick off today with some thoughts on one of our more recent books: Paths to Prison: On the Architectures of Carcerality. I’m going to move between speaking as myself and as the office since this project is both personal and, crucially, a model of what we collectively aspire to do at our imprint Columbia Books on Architecture and the City.

How you come to know this book today will be different from how you come to know it as a reader. And I think that is the point, in many ways, of this workshop. Asking and attempting to answer “why publish?” lets us consider not just the initial ambitions and motivations of each project but to speculate on how they might evolve to meet the present, as our books take on lives of their own after we’re apparently done.

I’d like to begin where the project began as a way to point where it might continue to go.

AIA, “AIA Board of Directors Commits to Advancing Justice through Design,” press release, December 11, 2020, link.

This book emerged out of frustration. Frustration can be an incredibly productive and generative space, especially when it is shared by others. My own, personal, frustration started in grad school (here at Columbia GSAPP in the Masters of Architecture program), with the very limited ways I was being trained to think about the prison system (i.e. Bentham and the panopticon); how I was being taught to understand architecture’s role, participation, complicity in the carceral state (i.e. through typology, limited to the actual spaces that make up the criminal justice system); how the field I was planning to enter did not seem to share, at least the curriculum did not seem to reflect, a politics of abolition (i.e. instead let’s build “better” more humane spaces of confinement and reform, reform, reform this so-called “broken system”).

This education is and is not (obviously) specific to GSAPP: There is this pretty enduring idea—in and beyond architecture—that the prison is something that is separate from the world; that it is only a building that one is put into and let out of.

And this kind of thinking has led to very narrow and limited political positions—particularly from architects—which are only concerned with “fixing” the system, like committing to not build solitary cells.

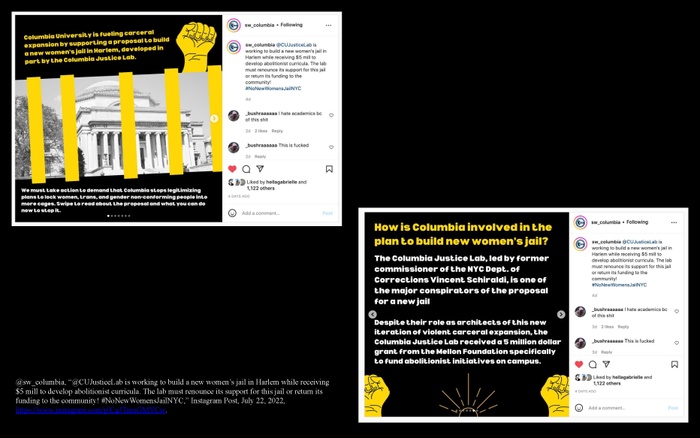

@sw_columbia, “@CUJusticeLab is working to build a new women’s jail in Harlem while receiving $5 mill to develop abolitionist curricula. The lab must renounce its support for this jail or return its funding to the community! #NoNewWomensJailNYC,” Instagram Post, July 22, 2022, link.

There is no better representation of how the carceral state actually expands by exploiting rhetorics of reform and justice than this. There is no such thing as a “feminist” jail, or a gentler or kinder regime of punishment. The conversation always stops short of abolition—stops short of proposing a world without such carceral state violence. Why is that?

adrienne maree brown, “We are in a time of new suns,” interview by Krista Tippett, On Being, June 23, 2020, link.

Towards the end of this conversation, brown asks “how do you personally begin to practice whatever’s in alignment with your largest vision?” What could this mean in the context of editing?

Thinking through what the carceral state is might help us think through what abolition demands of us all. There are many definitions of the carceral state—but at least in this book, it is used to describe the interconnected systems and institutions of white supremacy that impoverish, criminalize, police, punish people, according to race and class, so disproportionately poor people and people of color. And also very crucially, it includes systems and institutions that may not appear to be involved at all… This, to me, is suggestive of why and how conversations come to avoid abolition—because it points to how we might all, in our work, lives, relationships sustain the carceral state.

At least in my own experience, most people (and actually many architects!) still tend to think of buildings when they think of architecture. This book is working against that thinking. It’s trying to account for the logics and the beliefs that structure our world. We, as human beings, live in a society whose consciousness reproduces a systemic and personal politics of domination—and the same could be said about architectural consciousness.

Tamara Zeina Jamil, “Closing Act: Unbuilding Carceral Magic,” Avery Review no. 52 (April 2021), link; Gabrielle Printz, “Good Prison, a World Premiere,” Avery Review no. 37 (February 2019), link.

Some essays that put pressure and condemn various institutions of architecture––like Van Alan’s Justice in Design report, Frank Gehry’s studio at YSOA, and the AIA’s Code of Ethics (next slide)––for promoting the idea that we can even design our way out of the problems of mass incarceration through “good,” “better,” “reformed” prisons.

Malcolm Rio and Aaron Tobey, “Designing ‘Justice’: Prison, Courthouse, and Disciplinary Enclosure,” Avery Review 51 (February 2021), link.

Footnote 15: Treating mass incarceration as a design problem rather than as a broader social problem consequently forecloses both many means for addressing the architectures of mass incarceration in a systematic way and also reinforces a false sense that design is autonomous from the problems of politics and society; Malcolm Rio and Aaron Tobey, “That Is Not Architecture, This Is Not Urban Planning: Designing Disciplinary Obsolescence,” Frank News, May 31, 2018. Link

But back to frustration. How does frustration relate to publishing? Well, first, an imprint of a school of architecture, of a particular institution, should not just reflect that institution’s ideas and its discourses, but should act as an instrument to challenge and put pressure on it. The goal of this office is to identify the conversations/narratives/sites/ideas/places in our school/curriculum/field that need to be reoriented, redirected, and reframed. And it’s important that we decide this reorientation and redirection with others.

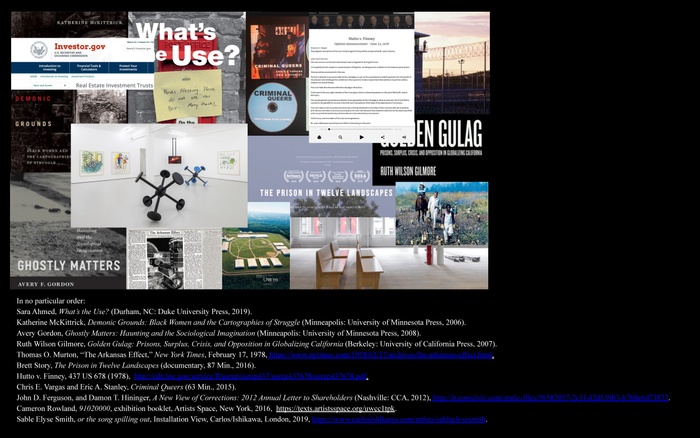

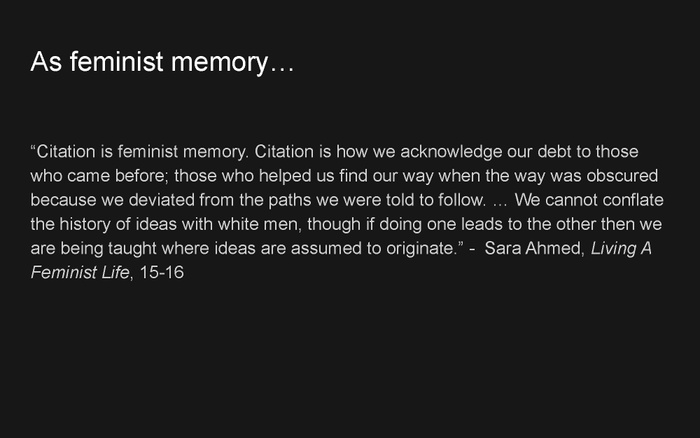

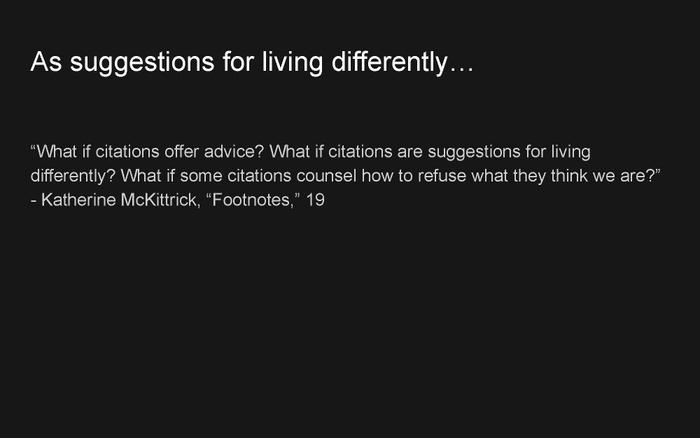

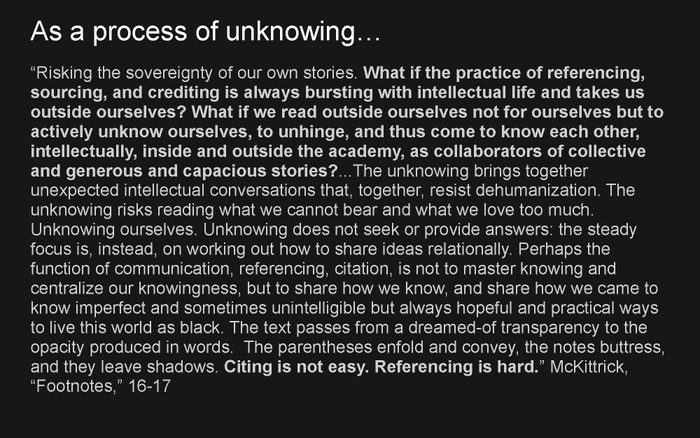

Where frustration led me, in no particular order: Sara Ahmed, What’s the Use? (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2019); Katherine McKittrick, Demonic Grounds: Black Women and the Cartographies of Struggle (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2006); Avery Gordon, Ghostly Matters: Haunting and the Sociological Imagination (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2008); Ruth Wilson Gilmore, Golden Gulag: Prisons, Surplus, Crisis, and Opposition in Globalizing California (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007); Thomas O. Murton, “The Arkansas Effect,” New York Times, February 17, 1978, link; Brett Story, The Prison in Twelve Landscapes (documentary, 87 Min., 2016); Hutto v. Finney, 437 US 678 (1978), link; Chris E. Vargas and Eric A. Stanley, Criminal Queers (63 Min., 2015); John D. Ferguson and Damon T. Hininger, A New View of Corrections: 2012 Annual Letter to Shareholders (Nashville: CCA, 2012), link; Cameron Rowland, 91020000, exhibition booklet, Artists Space, New York, 2016, link; Sable Elyse Smith, or the song spilling out, Installation View, Carlos/Ishikawa, London, 2019, link.

Where does frustration lead you?

Second, this frustration can lead you places: through books, to other disciplines, to archives. In the case of Paths to Prison, it led me across sites of oppression and resistance; through Black geographies; to abolition feminism. It grew with my own research tracing the architectural origins of the private prison corporation CoreCivic, which introduced me to a motel, a prison farm, a plantation, a supreme court case, a tax exemption, a landlord, and a developer… So even though CoreCivic is in the business of incarceration, its history, more than anything, confirmed that in order to understand and reject the “prison” we have to also look elsewhere.

What does it mean to author your own particular approach and role as editor?

Opening pages, i.e. alternate table of contents, i.e. various paths into Kirkham-Lewitt, Paths to Prison, link.

What is an editorial contribution?

Table of contents in Kirkham-Lewitt, Paths to Prison, link.

Third, this frustration can take different forms. My own intervention sits somewhere between introduction and contribution—between a specific historical thread that I’ve personally been following for years and the larger questions it poses to the discipline of architecture. I occupy a funny space between editor and contributor—two roles that have become quite inseparable for me over the course of this project and two positions that continue to direct approaches in the office.

And I guess I say this to invite you all to work from both positions; and to insist that to be an editor (of a book in this case) is to also model and author the terms of engagement.

What does an editorial conversation look like and where does it occur? Could it be an invitation? Questions that remind me of another question that adrienne maree brown asks in the aforementioned interview on On Being: “Is there a courageous conversation that needs to be had?” link.

A perfect response to a letter inviting someone to contribute to Paths to Prison. Email reads: “Sadly, I’m not able to take on any new writing projects until my stubborn book is done. I would be open to, perhaps, engaging in some other way (because it is such an important topic and architects are, for the most part, really the builders of death, from luxury condos to prisons to walls in the west bank).”

Perhaps more than anything I see this book as a set of invitations and starting points for architecture to think differently and more expansively. There are actually very few contributors in the book who would claim to know anything about architecture! It’s folks from American studies, gender studies, anthropology, English, Black studies. And this is a reflection of our work in the office more broadly; which is to challenge what texts, thinkers, disciplines, stories we consider relevant and irrelevant to us in this field… and to offer a guide for more research, more work, more action, and more resistance within and beyond the discipline…

So I’d like to end where the book “apparently” ends. The final pages of Paths to Prison are dedicated to a bibliography, which we like to think will push people out of this project and into the pages of others.

The bibliography is, in and of itself, an acknowledgment of how indebted this particular project is to other people’s work—which shows up in the volume in actual essays, excerpts, footnotes, citations, and attitudes. Writing carries all the ways one is formed in the world and rather than say anything new about this, I’ll wrap up by reading a line or two from the acknowledgments, which (for me) crucially precede the bibliography:

“No one writes alone. I never write alone. As an editor, I mean this quite literally. Most writing I do every day happens in the margins of someone else’s text. It is never done in isolation. It is always in dialogue. It is intimate, inconclusive, and reciprocal…”

And, so in the spirit of being in conversation with others, I’m super happy to be introducing Laura Coombs, who brilliantly designed this book. Laura is a graphic designer and creative director in New York, and a Lecturer at Princeton.

Guest Presentation On

Graphic Design

So in this presentation I’m going to talk about my practice, which is very physical. I think of this image here is a bit of a self-portrait.

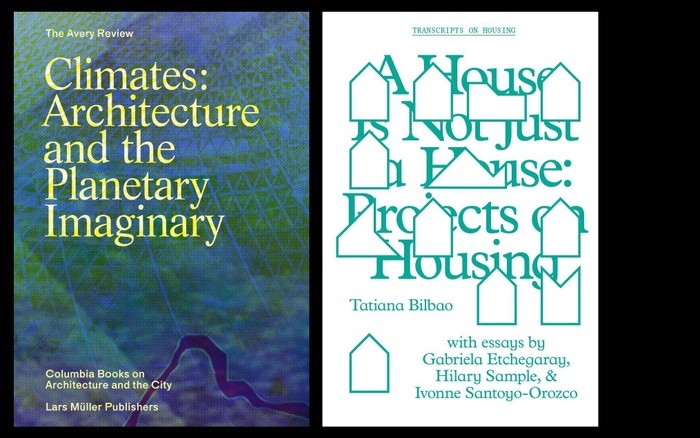

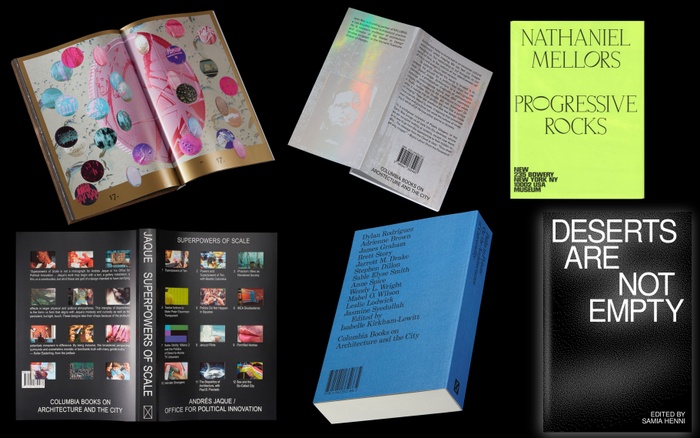

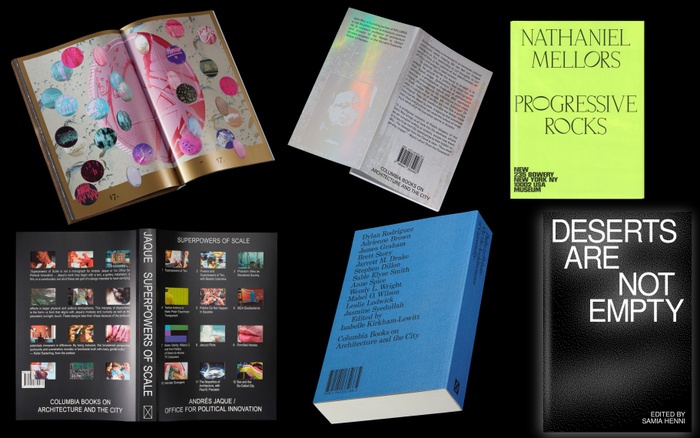

These are a few books that I have designed and that have been mass produced or are being mass produced within the past five years, and four of them are with Columbia Books on Architecture and the City. The blue one is Paths to Prison, as you can see there. In this presentation I’m including references that I’ve drawn on often over the years—not all the time, but they ebb and flow in my mind. It’s not that they’re necessarily so important, but as a resource for you all, I’m peppering them throughout my presentation, so you can look them up or think about them later if you want to.

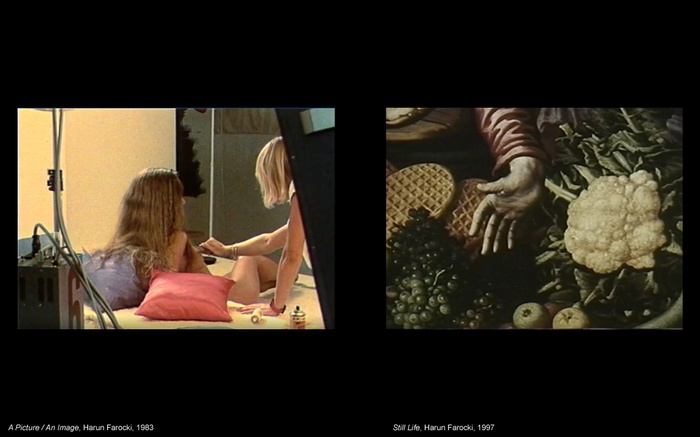

Left: A Picture / An Image, Harun Farocki, 1983

Right: Still Life, Harun Farocki, 1997

These are stills from two films by Harun Farocki. A Picture/An Image and A Still Life are a duration of films about making a playboy centerfold which actually takes quite a long amount of time. It can take an entire day to make one image and it’s quite a task that takes a lot of patience and care. I think this is a little bit like book design because there are so many variables—from the type to the image, from the materiality of the paper, to the way that it feels in your hand. How much you can read in one glance to how much you can read on one page—there are so many details that flow in and out of the process that make me think of image making as being truly adjacent to my line of design.

There are many increasingly divergent parallel universes, and I think about books a lot like this—that a book is usually a container for something that already exists or is existing or being edited all the time. In that sense, the book is of the same world but, but also exists a bit differently—divergently. And so there’s always this really interesting relationship between book and original content.

Having said that, the first way in which I’m going to talk about how I design books is through ink. I’m actually going to go back to grad school for the first project I’m showing you.

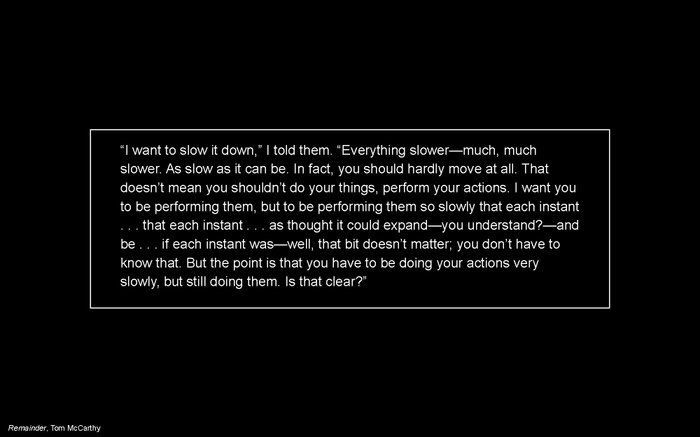

Tom McCarthy, Remainder, (New York: Vintage, 2007).

This is a quote from the book Remainder, which is kind of amazing because it has all of these sequences about slow motion and how the protagonist is asking everyone to slow down and reenact things. And I think the process of making a thesis book and probably the process everyone is going to go through to make a thesis book involves exactly that—a sort of slowing down. A reenactment or rethinking, a replaying over of something that you’ve already done and are then figuring out what to do with.

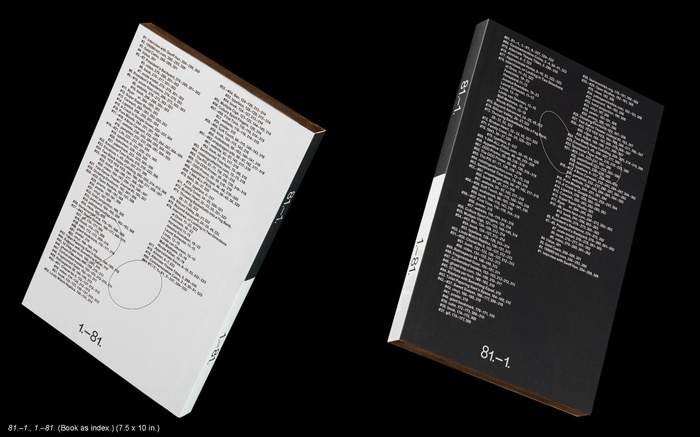

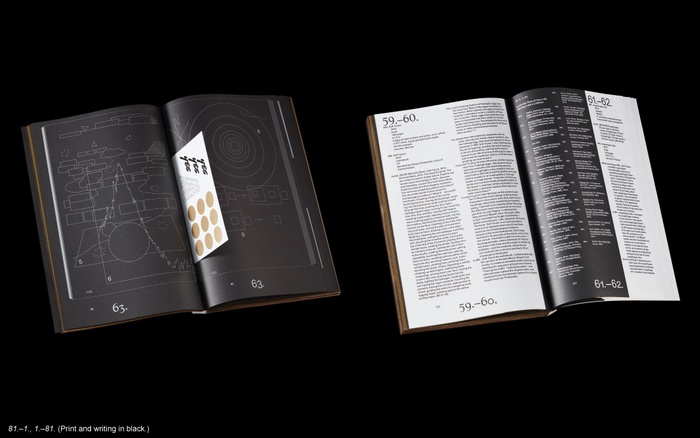

81.–1., 1.–81. (Collection of print and digital thesis work, 2015–2017.)

So what was interesting about my work in school is that it involved a lot of digital things. It was a lot of website design, a lot of motion, a lot of objects. There were print things too, but predominantly in school I was working in digital media. So, when it came to making a book of my work, these were the types of contents I had to wrangle together.

This here, for example, was a flower that existed online that reacted to speech commands. Through it, I had this virtual world that I was creating and living in. In that sense, it was not just a question of how to make a book for my own work, but then, how to make a book for a body of work.

81.–1., 1.–81. (Book as index.) (7.5 x 10 in.)

The way I decided to grapple with this was to create an index, which is very personal to how I think about things—in sequence. And so everything became numbered. Everything had an order. Everything I did started to be categorized. When the idea of an index emerged, the challenge for me was to figure out what that meant materially, as a student who had to produce it myself. I started thinking about materials and how materials could be indexical, like the book itself. So most of the work is in black and white, especially the writing and a lot of the print work.

81.–1., 1.–81. (Print and writing in black.)

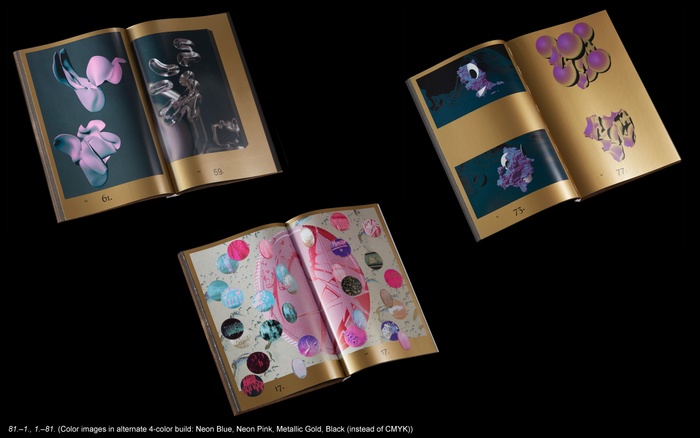

And then there’s other work that’s digital and in color. There were also other color spaces and materials. Essentially, what I decided to do was to make a color profile for the book that was specific to my work—one that could index the colors that I used most frequently.

81.–1., 1.–81. (Color images in alternate 4-color build: Neon Blue, Neon Pink, Metallic Gold, Black (instead of CMYK))

That meant that the black and white would remain the same, but that instead of CMYK, those four channels were replaced with neon blue, neon pink, metallic gold, and black because those were the colors that I was using the most. Treating the ink like this helped me think about it not just as something standard coming out of a printer, but as a channel of materials that could be purposefully deployed as I liked.

81.–1., 1.–81. (Gilding on paperback)

This is the outside of the book. It was gilded with gold, which speaks to another thing I’m really interested in, which is using historical aspects of graphic design in ways that feel a bit more contemporary. Originally, gilding was not just beautiful, but also functional. It helped to protect a book from bugs, mold, and moisture, which extended the longevity of the object. So this was all a little nod to that as well.

This ink-work appears in many of my other works, like Paths to Prison, where the blue color of the cover—which symbolizes an expanse, or the ocean, or something that connects us all—is actually in every image featured in the book as well. Every color image in the book has a little bit of that blue channel in it.

And so when it comes to image, books allow us to see things in different ways to experience them in our own time.

Books allow us to see ideas—through materials, construction, and physical properties, books embody ideas in their sequences, structure, and materiality. Each a unique new world of its own. Each book is a citation, an object that by its very existence, sources the ideas and situations of its author and its author’s ideas.

A book is a window into a world. A book about a cathedral can allow you to see the cathedral.

Speaking about architecture specifically, books are a natural extension of architecture, as architecture is deeply invested in written discourse, speculative projects, and representation of speculative futures and fictions.

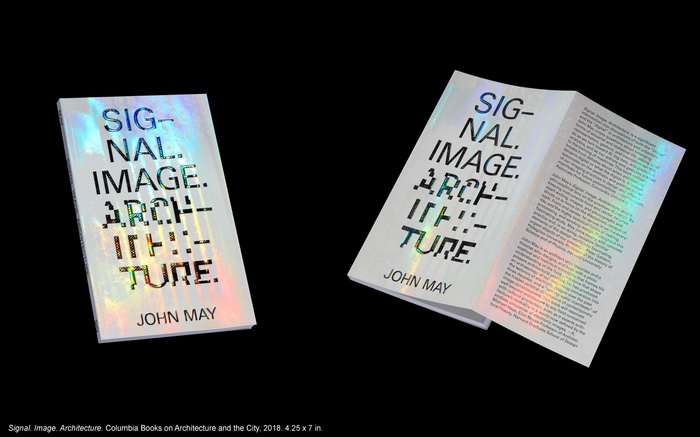

John May, Signal. Image. Architecture (New York: Columbia Books on Architecture and the City, 2018). 4.25 x 7 in.

This next book, Signal. Image. Architecture., is kind of meta in the sense that it’s all about image and how architecture exists as image before it exists as anything else. Because one of the things that I’m especially interested in overall is the construction of a given book, I questioned how I could possibly imagine this book itself as an image.

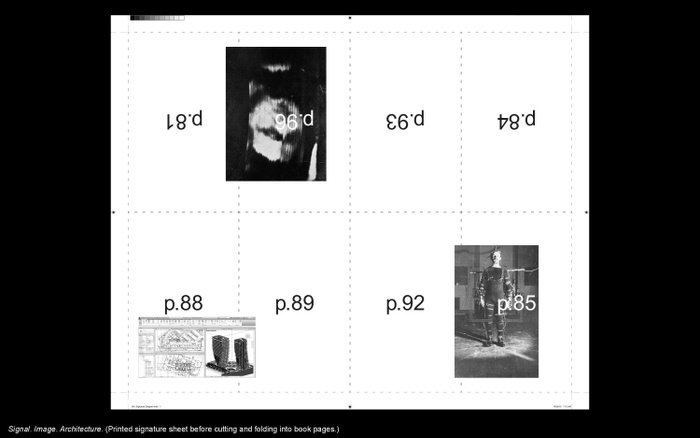

Signal. Image. Architecture. (Printed signature sheet before cutting and folding into book pages.)

When a book goes to press, the pages are printed on larger sheets and then they’re cut and folded down into a book. For this book, we imagined the broader sheets of the book as one image. We distributed and laid out the figures of the book on larger press sheets to think about them collectively as one larger image.

Signal. Image. Architecture. (Figures surface on / through multiple pages.)

What that did once everything was cut and folded down was create a situation where the images were flowing in and out of multiple different pages throughout the book. That means that you’re never really seeing the entirety of an image at once.

Signal. Image. Architecture. (Iridescent (not here nor there) ghost image; low resolution with hyper-sharp halftoning.)

The other thing we did was use this iridescent material on the cover. It’s neither here nor there. We then took a portrait of John Loggie Baird—the first image of television—and placed it on the back flap of the book underneath the author’s bio. It was meant as a small humorous gesture in which the author became his own work or something like that.

This other image here is the first TV image so it’s horribly low-res for today’s digital space standards. It became hyper halftoned when we made it in this material. In the end, the images do appear whole in the book, but only as notes.

Signal. Image. Architecture. (“Whole” images are endnotes.)

Next, I want to share a reference that I think is cool in an architecture context.

Octavia Butler in conversation with Samuel Delaney at MIT, 1996. (also referenced by Kameelah Janan Rasheed in the Creative Independent; also referenced by CSS in “Multidimensional Citation.”)

Fabric cover with metallic silver and black printing

Scheltens & Abbenes: Unfolded, Museum Jan Cunen, Oss, The Netherlands, 2012. 9 x 12 in. (Designed by Julia Born and Laurenz Brunner)

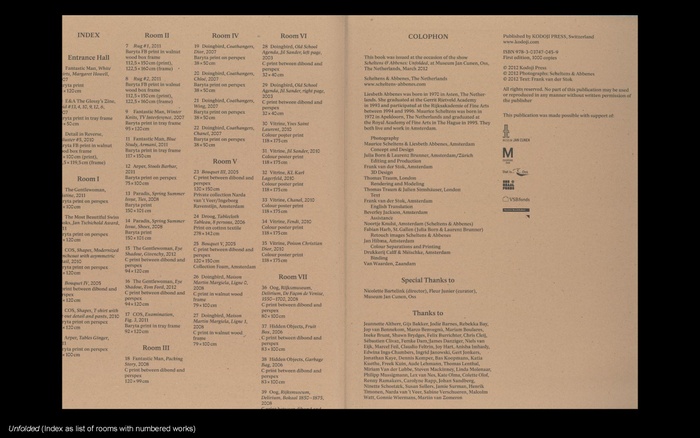

Unfolded (3D model, raster image rendering of exhibition wall title)

It’s a book, an exhibition catalog called Unfolded from 2012. It embodies a process that I’ve always personally identified with. The thing about exhibition catalogs is that museums often want to produce them before the show is up, which presents a problem because the art isn’t up before the show is up. So how do you make a book of an art exhibition before it’s actually put together? Usually the way people solve that is they feature images of artworks not in the show. Kind of a letdown, right? This book is really interesting because they had that same problem, but while planning for the show, they chose to make a 3D model of the actual exhibition and artworks. This book exists as an image of that 3D.

Unfolded (3D model, raster image rendering of exhibition wall text) (“An exhibition that can function as a book and a book that can function as an exhibition.”)

It, for example, opens with the title of the show and the wall text, which are both actually in a 3D model. That means what we are looking at is a rendering.

Unfolded (3D model of exhibition with typographic markers for Room #s and Work #s)

Likewise here, it opens with a rendering of the space that is not yet, but will soon be, the exhibition.

Unfolded (3D model of exhibition with typographic markers for Room #s and Work #s)

At the bottom of the pages, you see what look like room numbers but they’re actually artwork numbers and if you zoom in to some of the art, you can see other interesting details.

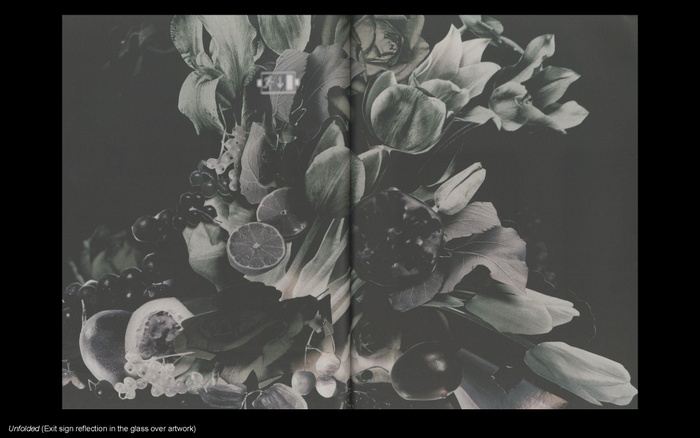

Unfolded (Exit sign reflection in the glass over artwork)

In the upper left of this one you can see the reflection of the exit sign in the work, so you still know that you’re in this rendering which is really nice, I think. And then at the back you get this index that lists which works are in which room.

Unfolded (Index as list of rooms with numbered works)

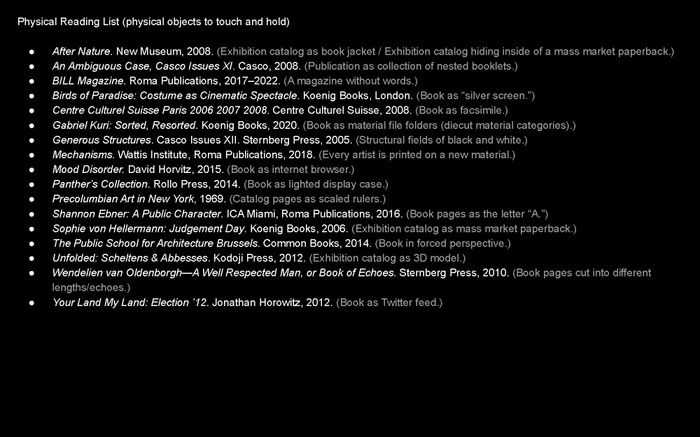

Princeton graphic design thesis crits, David Reinfurt, 2021.

I’ve included a physical reference list here. A good question to ask yourself when looking at any book that’s been intentionally designed is, “Why does this look the way it looks?” I love this question, and a colleague of mine at Princeton is always asking it at crits. It’s a great question, I think.

Some of these books on the list are criticism, some of them are catalogs, and some of them are other things, but they all have a physical idea about them and a reason for appearing and feeling like they do.

“The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction,” Ursula K. Le Guin. (with added words by Ignota Books, and also referenced in Multidimensional Citation by CSS published in The Serving Library, 2022.)

And then, this is just a shout-out to the book as a container that’s maybe more the star of the show than we then we give it credit for.

Here we are again, with some books that I made—a lot with you! Thanks!

Office of Publications Presentation On

Deserts are Not Empty

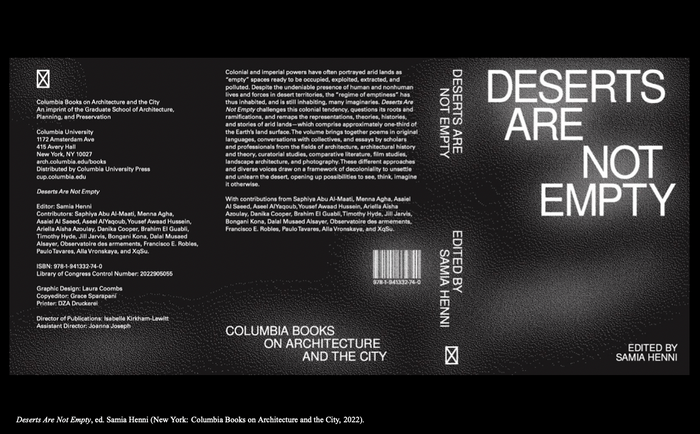

Deserts Are Not Empty, ed. Samia Henni (New York: Columbia Books on Architecture and the City, 2022), link.

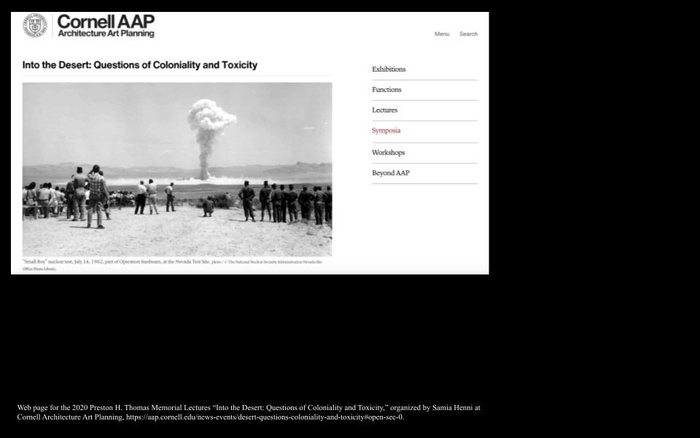

I’m going to introduce our newest book, which is currently being printed, Deserts Are Not Empty, edited by Samia Henni. Deserts Are Not Empty, like Paths to Prison, is a collected volume, and models a particular kind of book project we often do as an academic press—it is a book that was developed out of a conference (in this case, held at Cornell University in 2020) also organized by Samia Henni.

Web page for the 2020 Preston H. Thomas Memorial Lectures “Into the Desert: Questions of Coloniality and Toxicity,” organized by Samia Henni at Cornell Architecture Art Planning, link.

This kind of project exemplifies a particular mode of translation and iteration common to architecture and other academic and creatively affiliated fields. Publications are often born out of previous research, from other ways of developing and presenting ideas, both individually and collectively—whether that be through conferences, exhibitions, essays, lectures, etc. This process may be familiar to many of you working in student groups across different modes of research. And it is this kind of familiarity that we’d like to interrogate: why produce a companion publication? What is the function of an exhibition catalog, for example? What do they offer? Why is it that this genre is accepted as a given?

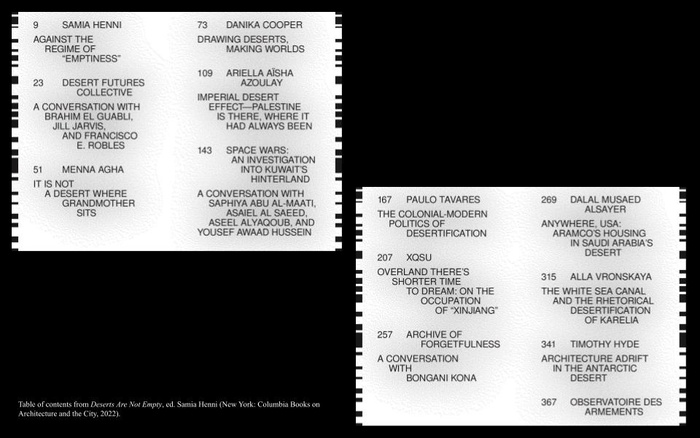

Table of contents from Henni, Deserts Are Not Empty.

Rather than seeing a publication functioning as merely a record of a previous event, we like to consider how a book—and both the possibilities and limitations inherent to its format—can be an opportunity to expand the work, or to reflect on what it means to revisit a project in a particular moment. Maybe it invites other ways of thinking from previous contributors, or new voices that might reread, not only the work, but the implications and impact of the event/topic/argument as a whole. In our case, coming in as editors to an already existing project and already existing editorial practice with Henni was extremely generative. It allowed for a way of working that was open, collective, against a kind of preciousness. It allowed for new ideas to be teased out, tested, and further transformed in exciting and sometimes unpredictable ways.

Deserts Are Not Empty scrutinizes dominant narratives, rhetorics, and ways of illustrating desert territories, to show how they have served to justify material, colonial, and extractivist transformations of the land.

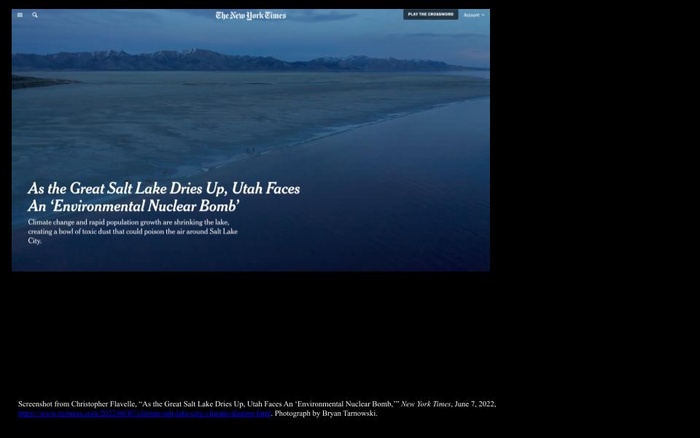

Screenshot from Christopher Flavelle, “As the Great Salt Lake Dries Up, Utah Faces An ‘Environmental Nuclear Bomb,’” New York Times, June 7, 2022, link.

These processes are enduring, responsible for past violences against peoples and environments that continue to impact the present and threaten the future. While it’s not featured in the book, one need look no further than the Great Salt Lake in Utah—which is currently drying up due to water irrigation, mineral extraction, and the broader effects of climate change—to witness how urgently these desert territories require our attention. In response, the publication insists on multiple forms of reading as an act of deconstructing the violence of colonial narratives of the desert and of imagining it differently.

Samia Henni, “Against the Regime of Emptiness,” in Henni, Deserts Are Not Empty, 9.

As described by Henni in the introduction to the volume, “The term ‘desert’ stands in for a complex locus of imageries, imaginaries, climates, landscapes, spaces, and histories,” and so the aim of the publication was to locate and challenge the confluence of material and immaterial forces constructing the so-called empty “desert.” The publication thus became an occasion to bring together, not only multiple voices, but a variety of formats, genres, and forms of visualization to enact—in a similar method to Paths to Prison—a particular mode of reorientation. The title itself, Deserts Are Not Empty, is extremely intentional in how it insists on a position, it immediately announces a project of refusal—to refuse, in Henni’s words, “the regime of emptiness.”

As critical investigations of desert narratives, the book welcomes alternative formats that reflect upon, challenge, and move away from dominant modes of writing and communicating that prescribe particular ways of ordering the world. The essays shift between genres: between academic, personal, visual, and narrative forms of writing.

Ariella Aïsha Azoulay, “Imperial Desert Effect—Palestine Is There, Where It Had Always Been,” in Henni, Deserts Are Not Empty, 109.

Azoulay, “Imperial Desert Effect,” in Henni, Deserts Are Not Empty, 114–115, 116–117.

Azoulay, “Imperial Desert Effect,” in Henni, Deserts Are Not Empty, 124–125.

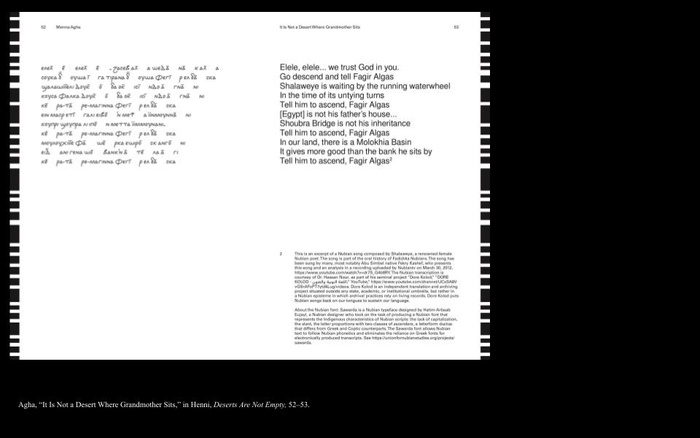

Menna Agha, “It Is Not a Desert Where Grandmother Sits,” in Henni, Deserts Are Not Empty, 51, 57.

Danika Cooper, “Drawing Deserts, Making Worlds,” in Henni, Deserts Are Not Empty, 73.

Cooper, “Drawing Deserts, Making Worlds,” in Henni, Deserts Are Not Empty, 90–91.

Cooper, “Drawing Deserts, Making Worlds,” in Henni, Deserts Are Not Empty, 106–107.

Timothy Hyde, “Architecture Adrift in the Antarctic Desert” in Henni, Deserts Are Not Empty, 341.

Hyde, “Architecture Adrift in the Antarctic Desert,” in Henni, Deserts Are Not Empty, 346–347, 348–349.

Hyde, “Architecture Adrift in the Antarctic Desert,” in Henni, Deserts Are Not Empty, 352–353, 364–365.

Ariella Aïsha Azoulay writes a fable to lay bare both the material effects and ideological tactics of Israel’s desertification of Palestine in the early implementation of the occupation; Menna Agha harnesses the tradition of oral history and storytelling to visualize forms of Nubian resistance and claims of sovereignty; Danika Cooper scrutinizes the violence of maps in directing extractivist logics and worldviews in the American West and proposes a counter-cartographic method of hybrid drawing; Timothy Hyde dissects a series of photographs of building in Antarctica to reveal the colonial, nationalist, and developmental biases that are always already contained in architecture; among many other forms of contribution.

Saphiya Abu Al-Maati, Asaiel Al Saeed, Aseel Alyaqoub and Yousef Awaad Hussein, “Space Wars: An Investigation Into Kuwait’s Hinterland,” interview with Samia Henni, in Henni, Deserts Are Not Empty, 143.

Abu Al-Maati et. al.,“Space Wars,” in Henni, Deserts Are Not Empty, 152–153, 164–165.

Alongside experimenting with modes of writing and imaging the desert, Deserts Are Not Empty also investigates existing models for collectively working on the desert. To engage the contours of this research, the book includes a set of conversations between Henni and three different collectives working across the mediums of print, exhibition, and radio that produce new forms of knowledge production, archiving, and the dissemination of desert histories.

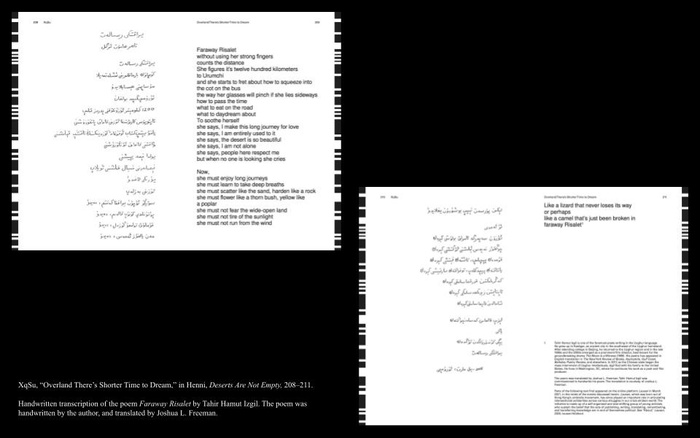

XqSu, “Overland There’s Shorter Time to Dream,” in Henni, Deserts Are Not Empty, 208–211.

Handwritten transcription of the poem Faraway Risalet by Tahir Hamut Izgil. The poem was handwritten by the author, and translated by Joshua L. Freeman.

The book gave authors the opportunity to connect with other traditions for seeing and recording the desert, and to expand the kinds of references typically associated with academic thinking. Prompted by Henni, the contributors were each invited to select a poem that somehow engaged the territory or notion of the “desert” to introduce their individual essays. This brought another kind of editorial engagement into the project, now led by the authors. The poems, which range from English to O’odham, Russian to Karelian, Arabic, Nubian, Uyghar, and so on, reflect alternative spatial accounts and imaginaries of desert territories, exploring the multiple forms of life and sociality that exist there. They also situate the writers, their work and their ideas, geographically, culturally, and personally.

Including and translating the poems into the publication as a matter of design also forced us to reckon with how to retain the aspects of accessibility, familiarity, and regional specificity inherent to these poems. We encountered problems and constraints that further evidenced the histories of colonial violence and erasure surfaced in the main texts, alongside glimpses of creativity and newfound agency formed against these histories.

Dalal Musaed Alsayer, “Anywhere, USA: Aramco’s Housing in Saudi Arabia’s Desert,” in Henni, Deserts Are Not Empty, 270–271.

Handwritten transcription by Dalal Musaed Alsayer of Ibn Rawās, ’Abd Allāh ibn Muhammad, Shā’irāt Min al-Bādiyah (Female Poets from the Desert), eighth edition, vol. I (Sharjah, UAE: al-rawy, 2002), 105–106.

Alla Vronskaya, “The White Sea Canal and the Rhetorical Desertification of Karelia,” in Henni, Deserts Are Not Empty, 316–317.

N.A. Lavonen, A.S. Stepanova, and K. Kh. Rautio, Karel’skie yegi (Petrozavodsk: Karel’skii nauchnyi tsentr RAN, 1993), 156.

Vronskaya, “The White Sea Canal,” in Henni, Deserts Are Not Empty, 318–319.

Handwritten transcription by Alla Vronskaya of a poem by Mikhail Florovsky. From Elena Volkova, “Poetry Lesson: Stone and Cross of the GULAG,” History Lessons, December 19, 2011, https://urokiistorii.ru/article/2746.

We often found that our US-based design program simply could not accommodate the foreign language type, which prompted us to ask the authors to write them out by hand to be scanned and placed in the book. This opened up a new set of concerns: several of the authors’ selected poems were not their native language, prompting us to commission transcriptions of the poems, or to scan them from their found sources. By contrast, due to other forms of colonial dispossession, authors were not able to write in their mother tongue, finding new forms of freedom and expression through the possibilities of digital type.

Agha, “It Is Not a Desert Where Grandmother Sits,” in Henni, Deserts Are Not Empty, 52–53, link.

More information on the Nubian typeface from Agah’s footnote: “About the Nubian font: Sawarda is a Nubian typeface designed by Hatim-Arbaab Eujayl, a Nubian designer who took on the task of producing a Nubian font that represents the Indigenous characteristics of Nubian scripts: the lack of capitalization, the slant, the letter proportions with two classes of ascenders, a letterform ductus that differs from Greek and Coptic counterparts.The Sawarda font allows Nubian text to follow Nubian phonetics and eliminates the reliance on Greek fonts for electronically produced transcripts. See https://unionfornubianstudies.org/projects/sawarda.”

While it may seem like a small set of transformations, the process of bringing these poems into a publication really demonstrates the ways in which, and here I borrow an idea from cultural anthropologist Mahmoud Keshavarz, political processes and positions are designed, and that design, in turn, is also always inherently political. This process, and the book as a whole, also demonstrates that, much like Isabelle has also illustrated, writing and publishing are always done in relation with others—people, ideas, landscapes—even beyond those actively in or contributing to a project. These both require care and attention, but also can provide new openings, new imaginations, or futures through written work. So as designers and those publishing with and on design, we invite you to consider the world of ideas orbiting your own; designing not just your intervention but how you intervene.

Thanks very much! I think this is a perfect place to hand the mic off to our next speaker, Nicholas Korody, who will be zooming out a bit to talk about his experiences with and approaches to working across various publishing formats… Nicholas is a writer, editor, designer, currently based in Milan. His writing has been featured in various publications such as Kaleidoscope, 032c, Pin-Up, Harvard Design Magazine, Metropolis, e-flux Architecture, as well as The Uses of Decorating, a collection of his essays published in Madrid in 2020. His visual work has been exhibited at various international institutions including Swiss Institute and the Triennale di Milano, among others. He and I actually run a research practice together, called Adjustments Agency, and he operates independently as Interiors Agency. Currently Nicholas teaches at the Design Academy Eindhoven and the Academy of Architecture Amsterdam, and serves as the editor of Capsule, a Milan-based design magazine. He is also a GSAPP alum, holding a Masters of Science in Critical, Conceptual, and Curatorial Practices.

Guest Presentation On

Format

Thank you for inviting me, it’s quite nice to think back on my career—or my practice—and that’s a tension that I’d like to speak to today.

As Joanna mentioned, I work in different fields—sometimes as a teacher, sometimes as a writer, often as an editor, and occasionally as a designer. Whether that’s installation, print materials, or digital really depends often on the context or assignment. And then, of course Joanna and I collaborate together, and we also work across media—often writing but also often not writing.

For a while, I kind of struggled with how to make sense of what I do because sometimes I feel like I have pretty little agency over it. It’s often just a brief of some sort that I then wonder how to mesh with the essays I publish or the other things I do. Recently I’ve been trying to understand what I do as a kind of expanded editorial practice across different media.

And so I’m going to try and talk through that today. I don’t want to talk about my own book or one of the things that Joanna and I might have done because there is often a lot of autonomy there in terms of format, but usually not a lot of compensation. And so I can’t only take those jobs; I have to also take other jobs which I do enjoy and so I don’t want to just disregard them here.

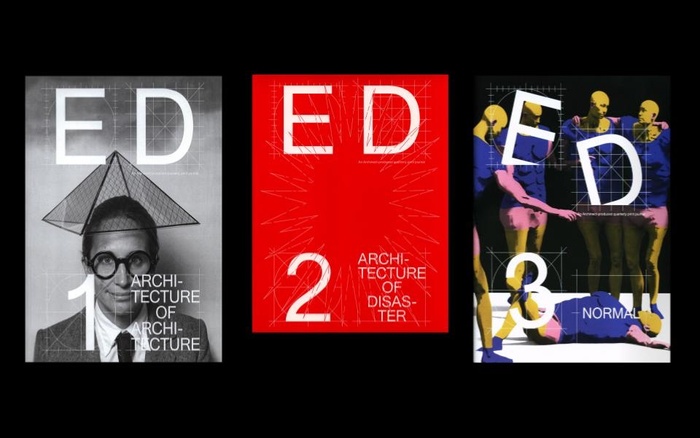

Covers of the first three issues of ED

I was quite lucky in fact that the first professional print project I had was ED. I’d worked for about five years as the managing editor of Archinect which maybe some of you guys know about? It’s a very old school architecture blog mostly used for job postings. It was one of my first jobs and was honestly great! It was a very supportive and cultivating environment and by about the third or fourth year I’d become the managing editor. It was then that the publisher invited me to launch a print publication.

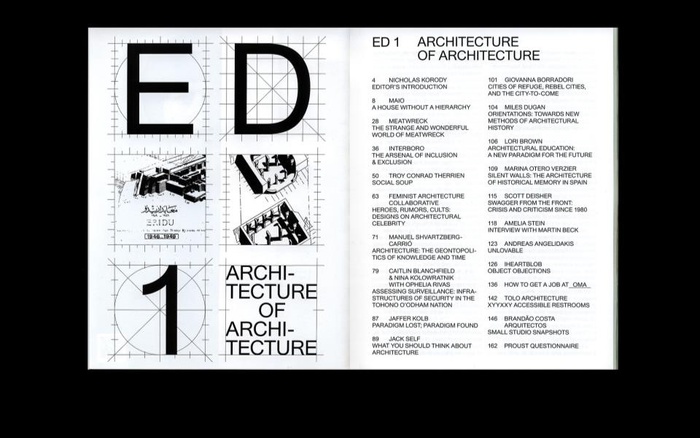

Table of contents of ED Issue 1: Architecture of Architecture

Joanna was my deputy editor—we’ve worked together in a lot of ways. In some ways, I think that the idea of starting off as the editor-in-chief of your own print publication is kind of maybe a dream situation for people who imagine wanting to launch an architectural publication. And it certainly was but in terms of format it was not really particularly radical. I think the design, which was done by Folder Studio in Los Angeles, is quite compelling and good, and the content was experimented with over the course of different issues.

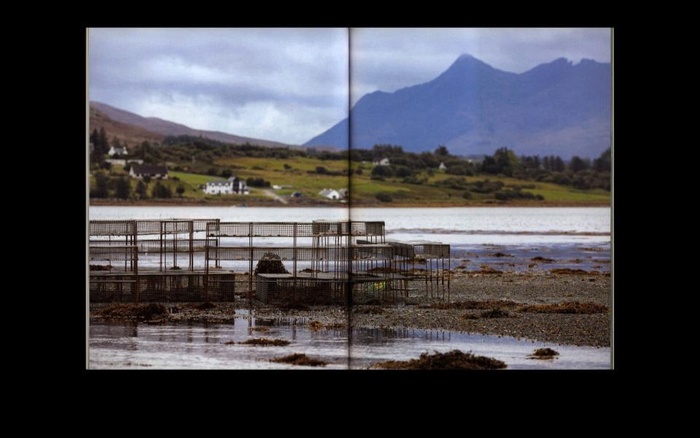

Spread featured in ED Issue 1: Architecture of Architecture

Spread featured in ED Issue 1: Architecture of Architecture

Table of Contents of ED Issue 2: Architecture of Disaster

On the one hand—and part of this, I guess, is that we were constrained by a certain brief—we had pretty much free rein, but on the other, the publisher wanted us to include built architectural projects from the website. And then the other kind of ambition of having a print publication is that we could invite writers or interview subjects who otherwise might not be that interested in being hosted on what was essentially an architecture blog. So the constraints, while kind of small, did determine the format. We’ve hosted philosophers who we thought were compelling at the time like Timothy Morton, or Cooking Sections, or Forensic Architecture.

Spread featured in ED Issue 2: Architecture of Disaster

By having a print publication, it became a kind of means of legitimizing Archinect, and we leveraged that legitimacy to get names and start conversations with people who might not otherwise have been interested. The flip side of it was that it was funded, so we didn’t have to worry about advertising, which was amazing. We weren’t dealing with really difficult deadlines, but it was completely unsustainable. Even with it just being a side project of an otherwise successful startup style business, it was really impossible for it to last.

Table of Contents of ED Issue 3: Normal

Spread featured in ED Issue 3: Normal

We ended up doing the third issue where we switched from offprint to digital press printing, which is—if you’re a book nerd—kind of a substantial depreciation in quality. It allows you to print cheaper, but even then, it still wasn’t really sustainable.

The other thing I want to quickly say about the format of this before moving on was that it was perhaps one of the reasons why we did involve again the kind of interviews, essays, and eventually short stories alongside more glossy photos and stories of people whose practices we liked.

But again, it was still kind of fairly typical and part of what determined that was the kind of goal, the ambition of its function, which was to legitimize an online platform. So in a way it was kind of a reverse of other narratives you hear, where you have print publications going digital. We were a digital native publication going print and the reason I’m saying all of this is that print signifies something else, compared to an online platform now. And it also comes with a lot of other costs.

Issues of Capsule Magazine

Spreads featured in Capsule

The most recent publication, I worked on was launched a month and a half ago and is called Capsule. And for this I have a copy on hand because it’s better to see it to scale.

The format is massive and is quite luxurious. There are several different paper stocks, there’s a comic book, a manga, and various fold outs. Look through it. It’s more of a beautiful object than it is a magazine, I would say. It’s an annual—it’s supposed to be printed once a year.

The downside of having so many different paper stocks and exciting different ways of presenting material is that the thing costs about $55. And so that produces a kind of threshold in regards to who can access it.

Spread featured in Capsule Magazine

Spread featured in Capsule Magazine

Spread featured in Capsule Magazine

I think, to work in print nowadays it’s hard to not be digitally aware. I don’t really know if the distinction matters as much. Although it’s a format you choose based on what you want the product to be, they can never exist completely outside of each other. For example, we have these short essays. This one is actually by Grace Sparapani who will be speaking in a moment. Each of the essays have the constraint of being able to fit on to an Instagram post, whereas all other aspects of the magazine have different forms of content.

I came into the project when it already had a team of designers—a defined aesthetic and approach. I think the format’s quite compelling, but it has, let’s say, a few downsides. It kind of prescribes what it does, how it operates in the world, where it will circuit, and among whom. Which isn’t to say that’s bad, but it fits in a certain place.

As I was mentioning, I’ve done all kinds of other projects, from working for luxury fashion brands to working on my own book of essays about political economics. And so it’s always been about trying to understand where the through line is in all of these works.

Title page to Le Da Costa encyclopédique

So I wanted to reference a precedent here to a project of mine that I am realizing has haunted it. It’s a publication that came out in the 1930s called Le Da Costa Encyclopédique. It’s a project that I’ve been obsessed with since I was like 18 and actually informed the first publishing project I ever started, which was a series of hand-bound artists books that my friends and I did when we had an artist collective. And it was very much just ripping this off. To give you a little bit of information about it, one of the main figures behind it was the philosopher George Bataille.

Identity Card of Georges Bataillie

Documents Outtake

He was a quite radical French philosopher, but people weren’t aware that he was involved in the project, including Bataille scholars until the 1990s, because nowhere in the pages will you find his name. Nor will you find the name of Marcel Duchamp, who was its graphic designer.

Before he worked on the encyclopedia, George Bataille, had done several other publishing projects, including Documents, which included a section that he called a critical dictionary. I’ll get to that in a second. There was Documents and there was also Acéphale, which were both magazines, but Acéphale was also a collective—a group or movement perhaps best described as a secret society.

A depiction of the acéphale

It was symbolized by this emblem. Acéphale comes from a Latin term meaning headless or without a head, and this became a symbol for their approach to knowledge and their politics which was deeply reflective on and in reaction to the rise of fascism across France at the time. Their critique of fascism extended into an understanding of the power of merit of fascism as a narrative, as a dominant and dominating narrative.

And one of their ambitions was to produce mythologies that could counteract those of fascism. This entailed a kind of self-mythologization. They started rumors that they were meeting in forests and going to sacrifice one of their participants. This story goes that they were all willing to be the sacrificial victim, but not a sacrificer.

I guess what I’m getting to is branding, because for a logo it’s pretty effective as well. It’s all so charged with symbolism: the intestines are exposed; the skull is placed where the genitalia may otherwise be.

In Documents, though, which was published around the same time as Acéphale, Bataille created this critical dictionary. It’s something he picks up in the encyclopedia where he takes images and he juxtaposes them with his own definitions. I think the one of architecture is quite interesting. He talks about architecture in two ways, one of which is to describe it through the use of the butcher house—the slaughterhouse. The second one is through the collapse of factories and prisons—which is perhaps an interesting link to what we were talking about earlier in Paths to Prison.

The gist of these anti-definitions, if you will, are to show how our very systems of knowledge—how we ordered them and how we present them—are reflections of a kind of broader ruling order and relations of power.

And the ambition was to use language, magazines, and publishing as a way to subvert that. But that didn’t just happen in terms of content. That happened on the page in terms of texts but also in terms of the broader object. And so, to pull out a few quick elements on this, the encyclopedia was designed and sold to appear very much like an encyclopedia.

And the kind of game they were playing was also invested in opposing the French tradition of encyclopedias that aimed to be a total structure of knowledge and a way of organizing that knowledge.

On the front page, for example, in place of where you’d normally have an author’s name, you had this—an image game.

It’s a donkey on a masthead or an ane au nid-mat—a homonym of anonymous.

When it was published and put in bookstores, it was labeled as Fascicule VII Volume II. The idea was that when a buyer would go into a bookstore they’d ask for the first part, which would turn out to be impossible. That, along with the anonymity of the author through the visual game, took the place of the publisher itself. With all of the texts written by different contributors, it resulted in a kind of headless publishing project.

And then on the inside, the first edition was entirely E’s—definitions starting with the letter E. They did actually have their signatures in the form of their fingerprints. But here they’re represented almost like the bark of a tree.

After putting these in bookstores as incomplete editions they also published announcements and advertisements like, for example, this one in the London Gallery News. It says “Da Costa Publishes his Encyclopedia in Paris,” therefore gesturing towards an author that isn’t even there. I find this all very fascinating to think about; how to inhabit the tropes rather than to simply, say, do away with it all. In this example, they chose to instead take on its form and undo its logic from within. They identified what in the format of the encyclopedia produces its authoritative role as a ruling logic, which brings me to a project that I’ll talk about briefly next.

Cover of 032c Magazine

I was invited to do this project after I graduated from Columbia. Some of you guys might know 032c Magazine. It’s a Berlin magazine that’s operated since 2002 and is now in it’s 22nd year. At the time it was first released, this was the first edition. It was a newsprint famously designed by Mike Meiré, a big German designer.

This is a pantone chip, and the name of the magazine is, hence, the pantone color 032c.

By the time I started working there, they had already evolved into an apparel brand—first in T-shirts and then later in a ready-to-wear line.

Not here to judge today, but we can just say it had kind of escaped its original role as an underground or rebellious or counterculture magazine and had become, I think, part of the dominant culture it was first designed to resist.

First ever image of a black hole as imaged by the Event Horizon Telescope in 2019

Memes of the first black hole image

I was asked to do a contribution, and we were discussing it over the course of a year and around then, this image came out. I’m sure many of you guys saw it, the first image of a black hole produced using computer processing—it’s not a photograph.

It quickly spiraled across the meme-world on the one hand as a joke about “profile pics vs tagged pics” because of how unimpressive it was as the first image of a black hole. I should mention that this project was done collaboratively with the editor of 032c, Victoria Camblin.

What we thought was interesting while working on this together was how the black hole poses no risk to any of us, but it became almost like a kind of magnet or condensing mechanism for all the kind of anxiety and anger that we live in today, particularly in a moment of ecological collapse. It reminded me a bit of the Whole Earth Catalog which I’m sure anyone who’s passing through GSAPP is probably quite tired of hearing about.

It was a kind of seminal counterculture magazine which featured the first image of the Earth from space. It was also kind of narrativized/historicized as being the progenitor of modern environmentalism on the one hand, but also as a form of knowledge akin to the Internet on the other because it quite literally influenced Silicon Valley overlords.

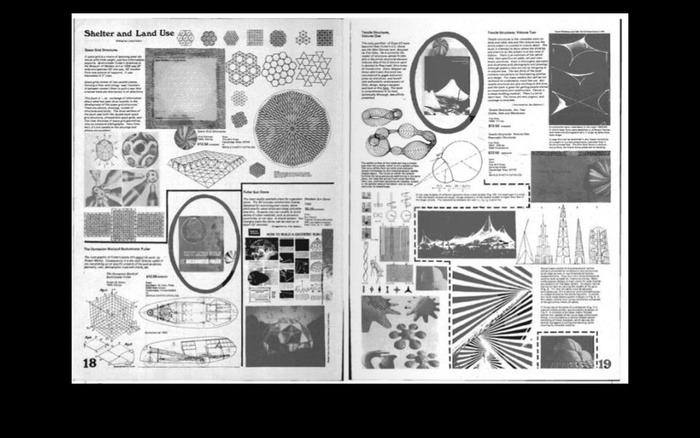

Spread from the Whole Earth Catalog

I guess to bring this back to Bataille and to make this a bit more cohesive, I’ll say here that the idea was to deflate it from that original reading. It was less about it being a kind of precedent, and more about it being something that came after, something that could be better understood, perhaps, along the lines of a Victorian decorating guidebook. It’s essentially a catalog of things to buy and by buying them you produce a way of living in the world. And that living in the world has a certain ecological weight.

I would argue that perspective or that politics is quite inadequate for the ecological crises we live in today and of which they did not know of at the time. It is essentially a tool book or a shopping guide for masculinity. We decided to inverse that and explore the Whole Earth Catalog through extinction and through the same effect of nihilism but also humor.

Part of that was quite literally subverting the famous lines of the Whole Earth Catalog, “Stay hungry? Stay foolish?” We added “In this economy?” as well as some question marks.

But also, we were kind of trying to essentially subvert—both through graphics and text—the sense of Promethean or Herculean masculinity that we read in the Whole Earth Catalog and the environmentalism it began.

We wanted instead to look at environmentalism—or at least at an image of environmentalism—that suggested exertion, a sense of not being able to support this way of life anymore.

Our reading was informed by what was happening at the same time, which was an environmental discourse called the Friday for Futures movement. It was led by a figurehead who kept saying over and over again, “Our house is on fire,” and so we became interested in the metaphor of a house and wondered what it meant if we were no longer at home since everyone’s house was on fire.

Against this kind of off the grid ethos we proposed a new interior.

To draw on the readings of Bataille and the encyclopedia, this was also an exercise in classifying things, in putting things in juxtaposition, while still investing a sense of humor into the work.

This exercise extended to the materiality, where there were different paper stocks used: uncoated pages versus the glossy ones for these.

It therefore presented a certain way of reading the knowledge, where, for example there were links that were in blue versus links that were in purple.

There was then also advice that ranged from building a guillotine to buying a butt plug.

By juxtaposing these without much editorial constraint, we wanted to subvert the idea that A) environmentalism could be easily bought or that it was a cohesive product that could be purchased while B) inhabiting the fact that this was a fashion magazine inside of which we’re selling all kinds of ads.

We produced different ways of getting it out there, including a face filter which, because of 032c’s audience, included a lot of shirtless men.

Ad Campaign for Balenciaga designed by Nicholas

And then later this was a campaign I worked on for Balenciaga where I seeded the same images back into a video game.

The idea was essentially to produce a game that could operate within the different briefs I’m given and address with my different collaborators.

I think I’ll stop here. Thank you, guys!

Office of Publications Presentation On

Avery Shorts

As an assistant editor, the day-to-day work I participate in might be described in practical terms: I support the editorial workflow and production process for the Office (specifically, for the Avery Review). This includes: talking with authors, editors, and copyeditors; laying out and proofreading texts; and the post-production and outreach efforts of the journal. However, I wonder if we might contend with this work and labor a bit differently in the spirit of the workshop, since (as Isabelle and Joanna have emphasized) the question “why publish?” is staked in this everyday work, and the work we do, collectively, as an office.

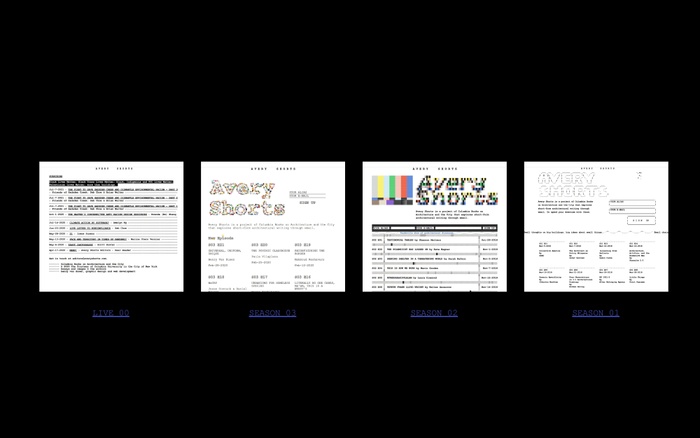

I’ve been thinking about organizing a new “season” of our Office’s email-based journal, Avery Shorts, and I’d like to use it today as a kind of space of analysis to push and interrogate our own belief that “why and how we publish is just as important as what we publish.” So in asking y’all to reflexively think about what is at stake in putting something out into the world (especially but not exclusively at an ivy-institution like Columbia), I am—and we are—continually asking this ourselves.

Avery Shorts explores short-form architectural writing (typically 500 words or less) through email. In other words, we ask readers to opt-in to (to subscribe or sign up to) an email letter chain:

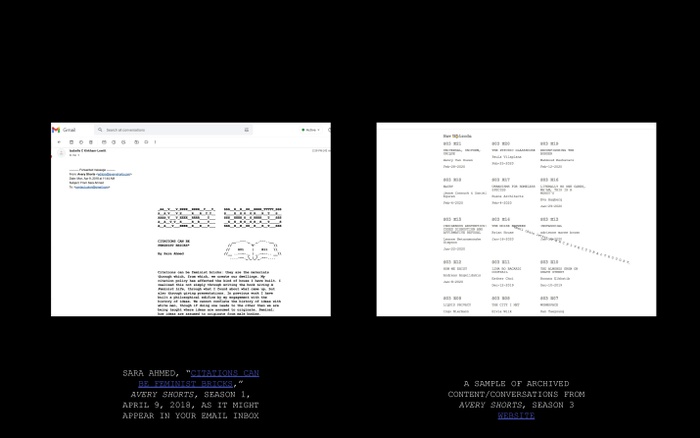

Sara Ahmed, “Citations Can Be Feminist Bricks,” Avey Shorts Season 03 (April 9, 2018), link. Screenshot of how Avery Shorts might appear in your email inbox.

the email inbox (then) is the primary mode of delivery and circulation for Avery Shorts,

while averyshorts.com, the website, archives this form of communication. This mode of exchange biases a different set of possible actions and ways of interacting with content and with others. For instance, unlike the general distribution and circulation of printed matter (constrained by and to certain places and people ), Avery Shorts enables forwarding (with or without commentary) and a kind of sending and receiving that feels more intimate and more informal, which, in turn, shapes how and what we communicate.

This mode of communication (email) and this archive or record of communication (the site) ultimately co-constitute the “what” of Avery Shorts, or…

“[the] space for sharing half-baked ideas, for staring-into-the-void thoughts, for sleepless tangents, excerpts, images, questions, and projects you can’t get out of your head…”

As a project that was born and lives on the web, this content (also knowledge) circulates differently than printed work: this means that it is read differently too. As an exercise in short-form writing, Avery Shorts also enables exercises in short-form reading. This content exists free and online, which is an intentional politics part of a larger conversation about/around public scholarship + open access—

Andrea E. Pia, Simon Batterbury, Agnieszka Joniak-Lüthi, Marcel LaFlamme, Gerda Wielander, Filippo M. Zerilli, Melissa Nolas, Jon Schubert, Nicholas Loubere, Ivan Franceschini, Casey Walsh, Agathe Mora, and Christos Varvantakis, “Labor of Love,” Commonplace, link.

on the unevenness of how we know what we know (in other words, epistemology), on paywalls, intellectual property, and so on. But while being free and online makes Avery Shorts a more-accessible archive and record of published content,

questions of accessibility are not so easily settled and resolved…

The format of Avery Shorts emerges from the everyday interfaces and infrastructures we use to communicate and the various ways in which we consume, and are beholden to, timely content, contact, and connection;

critically inhabits these forms in recognition of that monetized and colonized use, attention, and economy, particularly as they are reflected in architecture:

Can a publication or publishing be sporadic and messy, an improvised and informal record of processes, impressions, and reflections?

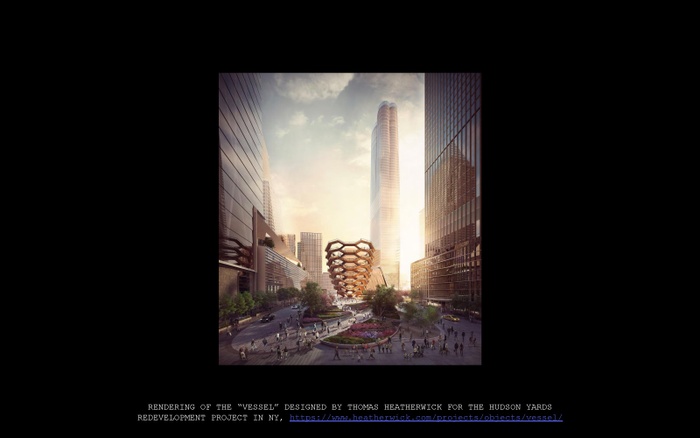

Rendering of The Vessel designed by Thomas Heatherwick for the Hudson Yards Redevelopment Project in New York, link.

Can it be a position (or resistance) against what is deemed a loss of value and productivity in our discipline, field, practice, and a culture wedded to glossy renderings, polished perfection, and solution-driven design…

![IT presentation slide: clip of students working 24/7 [3/3/11 2:04AM TO 3/9/11 5:19PM] from Dan Taeyoung, "GSAPPcam timelapse (incomplete)," Vimeo, March 9, 2011,](https://d37vpt3xizf75m.cloudfront.net/api/file/HJNNrtjMQwueurDp8CpI/convert?fit=max&h=550&w=700&compress=true&fit=max)

Clip of students working 24/7 [3/3/11 2:04AM TO 3/9/11 5:19PM] from Dan Taeyoung, “GSAPPcam timelapse (incomplete),” Vimeo, March 9, 2011, link.

…but where the catch (exhaustive unpaid labor) [often] nullifies the payoff (expertise)?

In April 2020 (during the early months of the pandemic and a month or so before the heightened visibility of uprisings in the US and globally), the office shifted from “seasons” (1, 2, 3) to Avery Shorts Live. This was a way to conceptually lean into the possibility of a publication-as-infrastructure: a fundamental armature that supports and sustains thoughts and ideas as they arise and unfold around us—however their unfinishedness or messiness. Avery Shorts Live was something folks could tap into as needed… that tapping into simultaneously produced a way of sending and receiving ideas, a way to access editors, and a way to record a moment in time.

All of this contradicts what is generally thought to be publishable material, encouraging us to make space for what we consider unpublishable material. (but) This fronts many other questions:

What kinds of privileges (e.g, time, education, resources…) do you need to have in

order to be published or “publishable?” This presses upon language, value, and use:

What is valued and useful (or of use), and what is not? How and why?

What (or whom) slips below the legibility of publication or is perhaps left behind in the usual rhythms of publishing?

Such questions underwrite what it is that we do, or to put it another way: we are delimited by the networks we exist and circulate in. Ultimately, it takes a lot of consideration and care to reconfigure a more-just editorial and intellectual practice and to make all the processes, transactions, and exchanges behind publications permeable and transparent.

Avery Shorts is a product of community; it is what working together on a publication project might look like; it models a collective form of (editorial) exchange (where your work appears through the work of others; where your labor is tied to others; and where your work exists only by engaging persons external to yourself), but as a model, it also bears witness to limitations and those (equally collective) consequences. Nonetheless, that restriction of possibility (though certainly a material one) can be taken up queerly to enable different intentions that are not exhaustive of possibility. I think the project of publishing bears exactly that political responsibility:

to be clear, unafraid, and forceful in your intentions—to wield them as method and technique. Because the ongoing result may offer and lend, in turn, new concepts for unlearning and processing our worlds.

Okay, so I think that’s a good place for me to end (on this screenshot from the Avery Review)…

Our next guest, and also a brilliant colleague, is Jacob R. Moore. You might know of Jacob, or be familiar with his work, through all the urgent organizing he has been doing at the Buell Center as Associate Director there. Jacob is also a critic, curator, and an editor. Prior to joining the Buell Center, Jacob worked as an editor at Princeton Architectural Press. His work has been exhibited internationally, and he has been published in various magazines and journals from Artforum to the Avery Review. As a founding and contributing editor of the Avery Review, Jacob is an integral part of the journal—and crucially, an important part of where it is today. Jacob, we are so happy (and thankful!) that you are able to join us (online) today…

Guest Presentation On

Avery Review

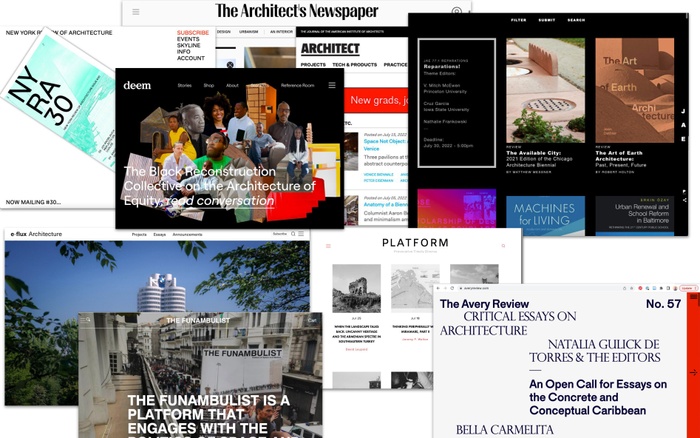

From left to right, top to bottom: Archdaily, July 26, 2022, link; Architizer, July 26, 2022, link; “What Frameworks Should We Use to Read the Spatial History of the Americas?” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 81 (2): 134-153, June 1, 2022, link; Designboom Magazine, July 26, 2022, link

Thank you very much for the invitation and that really nice introduction, and thank you everybody for putting so much on the table to think about and think with. I’m going to try and be relatively quick and pretty informal here since I hope that we can talk about a lot more of this in the Q & A.

As Isabelle (Tan) mentioned, I’m a contributing editor for the Avery Review, and I’ve been part of the journal since its founding in 2014, so I’m just going to really quickly give an overview of what the Avery Review was: how it was a version of our own “why publish?” and how that conversation was for us at the beginning and how it has evolved.

So basically, in 2014—this is a quickly assembled representation of what for us felt like a real dearth of open access online space for medium-form original critical writing on architecture, so this is not meant to be comprehensive and obviously these are from recently—but the point was that there was a lot of PR-type writing, which still very much exists. PR stuff would be put out by people representing their own work, usually; so: not very critical, really image heavy, etc. Alternatively, there were slower burn pieces in academic journals (e.g., Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians) that were behind paywalls, and let’s say the urgency that they carry is a very different kind of urgency that is much slower “cooking.” So as readers, basically a few of us—what became the founding editors of the journal—noticed this, and we noticed this initially as readers: what felt like a kind of missing middle (for lack of a better framing).

We turned that curiosity or desire for a middle ground as readers into something we could work on as editors. I wasn’t really sure how to represent the earliest days of the journal—looking at this, it feels like this Issue 1 of the Avery Review was 17 lifetimes ago, but it still seemed somehow appropriate—so basically we came together and decided to do something to fit in that space that we noticed being open. And what I want to focus on today is the way that we, at the beginning, tried really hard—and have continued to try really hard—to keep our approach really simple: we had a limited set of parameters that we all agreed upon and have stuck with them to the present day. I’ll talk a little bit about what I think that has allowed for, and maybe in the Q & A, we can talk about how that is or isn’t transferable to other kinds of projects.

Building out of the need we had noticed, we wanted to do something that was text forward rather than image forward—something that had a really regular rhythm, so there would be a contemporaneity to it that was going to be about stuff happening “now,” as it were, but that wasn’t going to be knee jerk, press release kind of material. We also really wanted to get authors to step out of their own work—again, working against that sort of PR register that architects often end up writing in, usually about their own work—so we made a rule: the authors always have to engage with the work of somebody else. And so, as in the title, the Avery Review, the review format became the way we have organized that requirement; so there’s always what we call “an object of review” that our authors are required to engage with. And what that object is can be many things, but we are pretty intense about insisting on that. And that’s pretty much it.

We worked really hard to come up with those core tenets and then wanted to leave the rest really open. It’s cliché, but what I want to underline is: that simplicity gave us the ability to be super rigorous, while also having tons of flexibility and freedom to play, and I think authors and other interlocutors have been able to feel the kind of freedom that comes with that. It’s cliché to say that with rules comes some kind of—I’m gonna say freedom again—but some kind of looseness comes with it, once you have just a short list of things you really are going to stick with.

This is Issue 1 and we have 57 issues now, and I could talk through different pieces that really are illustrative of those exact rules, but what I wanted to talk about were the moments that we were sort of able to break out—or not break out of those rules—but do something a little bit unexpected that built upon the sort of structure that we established:

James Graham, Alissa Anderson, Caitlin Blanchfield, Jordan Carver, Jacob Moore, and Isabelle Kirkham-Lewitt, eds. And Now: Architecture Against a Developer Presidency (New York: Columbia Books on Architecture and the City, 2017).

James Graham, Caitlin Blanchfield, Alissa Anderson, Jordan H. Carver, Jacob Moore, eds. Climates: Architecture and the Planetary Imaginary (New York: Columbia Books on Architecture and the City, Lars Müller Publishers, 2016).

James Graham, Caitlin Blanchfield, Jordan H. Carver, Jacob Moore, eds.,

The Avery Review: Chicago (New York: The Avery Review, 2015), link.

“The Avery Review Essay Prize 2020,” Avery Review, link.

“The Avery Review Guest Editor 2021,” Avery Review, link.

By the time some of these projects came about, we had a kind of identity and a set of readers that sort of would go with us because of the consistency we had by then been working with for some years. These are just a few of what we call “special projects.” So, we’re a primarily digital outfit, but in very key moments, we have chosen to go print. We did a broadsheet for the first Chicago architecture biennial. We felt that because, you know, the biennial was an event in space across the city of Chicago, we knew that a broadsheet would circulate—a printed object would circulate differently there—and we felt we had a real opportunity to sort of intervene in that moment. It was a pretty (I think) meaningful moment in architecture culture, at least here in this country, and doing something printed felt like a unique opportunity and even responsibility in that moment.

Similarly, the book And Now: Architecture Against a Developer Presidency on the left was published after the election of Trump. We felt really strongly, as an editorial collective, that something had to get done; we were having a lot of really intense email conversations and came to the idea that this too was an opportunity to condense work that was happening online, but into a printed object. And similarly, for the Climate’s book Climates: Architecture and the Planetary Imaginary: that was something that happened a little bit later and was a longer-term project but it also catalyzed work that exists and was able to exist online but also in print—and then the printed object was the vehicle for various public programs that we did. And as has been discussed here, printed matter circulates a little bit differently than the online essays do—though, they all existed online as well.

The two other special projects that are here, the 2020 Essay Prize and the 2021 Guest Editor—alongside the Avery Review masthead. We have an essay prize that’s a student essay prize that has now been going for (I think) five years. And a guest editor role (that used to be called the editorial fellow) where we bring on a fellow or guest editor for a year, who works on a special project with us.

I could talk about each of these in a little bit more detail, but I wanted to put some of these special projects on the table (and I’d be curious to hear Isabelle [Kirkham-Lewitt] and Joanna talk about this too) that I think were possible precisely because we had set a really solid frame for all of our work with those really simple rules. These special projects follow those rules very directly: every essay in these pieces has an object to review; the authors step outside of their own work and engage with the work of someone else; and they’re usually about between 2000-5000 words.

But they’re really different kinds of projects beyond that: they really speak with and in different tones to different audiences and to different topics.

Office of Publications Presentation On

Footnotes On…

Hi everyone, it’s so nice to be sharing this space with you today! As the assistant editor to our books division, I’ve had the chance to collaborate on the planning and production of a few really exciting projects thus far. They typically take the form of longer edited volumes like the ones Isabelle and Joanna have already spoken to, but also extend to shorter-form editorial experiments like the Footnotes On… series. In the same way that my fellow assistant editor Isabelle Tan has assumed care of (among many other things) the office’s work on Avery Shorts, I’ve begun thinking about how to continue the work of Footnotes On…

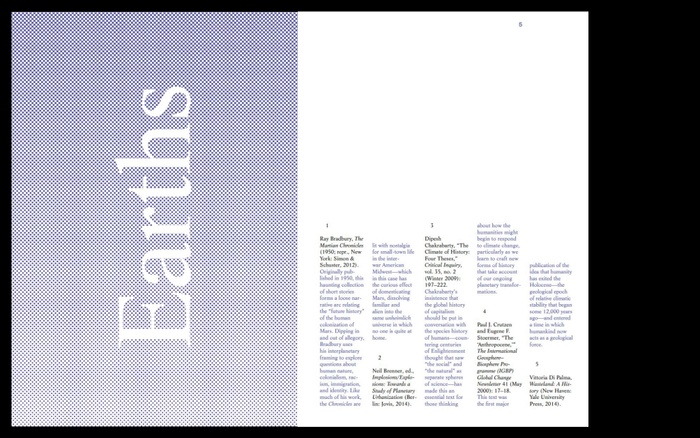

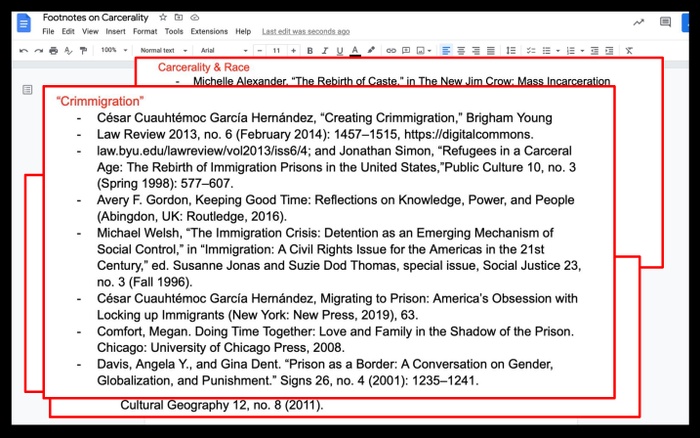

Spread from Footnotes on Housing: A Reading List