Dedication

Many people were instrumental in our research and in bringing this publication to fruition. Thank you to the LGBT Historic Sites Project, especially Andrew Dolkart, for providing information essential to this project and for the enthusiastic participation throughout. Thank you to the diligent QSAPP alumni brainstormers and researchers who supported and enabled our work on this project. Through their original Disappearing Queer Space proposal, and the group’s 2020 manifesto In Solidarity, With Gratitude, they advocated greater diversity within Columbia University GSAPP. This includes Alek Tomich, Nelson De Jesus Ubri, Sebastian Andersson, Jared Payne, Emily Kahn, and alumni advisor Gwendolyn Stegall.

Thank you also to the GSAPP administration for supporting this project, both financially and organizationally. Thank you to Michelle Zakson and Helene Zazulak Fransz for proofreading the text, and thank you to Mario Gooden, Andrés Jaque, and Justin Garrett Moore for their design and theory consultations.

About

Queer Students of Architecture, Planning, and Preservation (QSAPP) is a student organization at Columbia University with members who are in the Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation (GSAPP) in New York City. We seek to foster both conversation and community among LGBTQ+ students, their allies, faculty, and alumni of GSAPP. We actively explore contemporary queer topics and their relationship to the built environment through an engagement with theory and practice. Founded in 2014, QSAPP has participated in and presented numerous events and projects, including Coded Plumbing, a project about gendered restroom design; a lecture by Joel Sanders, author of Stud: Architectures of Masculinity; and, a symposium in honor of the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall Riots, Stonewall 50: Defining LGBTQ Site Preservation. We also published another book titled Safe Space: Housing LGBTQ Youth Experiencing Homelessness in 2019. This is QSAPP’s second publication.

Queer Students of Architecture, Planning, & Preservation

qsapp.gsapp@gmail.com

http://www.qsapp.org/

Authors

Abriannah Aiken - co-leading chair

Rourke Brakeville

Leon Duval

Adrianna Fransz - social media+graphic design chair

Ruben Gomez

Kelvin Lee

Jerry Schmit

Brian Turner - co-leading chair

Josh Westerman

Daniel Wexler

Preface

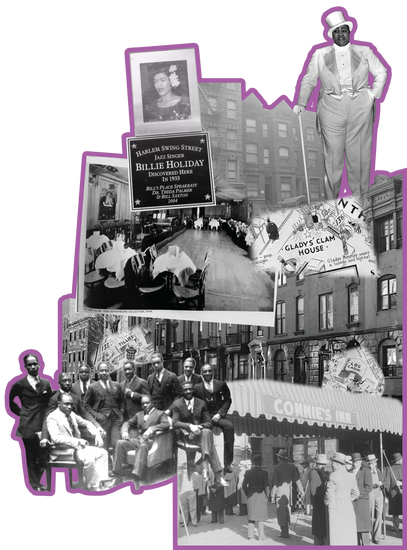

Historically, queer identity has been one of discrimination and limitation throughout history; yet, certain spaces throughout time allowed for self-expression. The Harlem Renaissance was one such place; it was “surely as gay as it was Black,” notes prominent historian Henry Louis Gates.1 Widely acknowledged for liberating opportunities to express identity in the Black community, the Harlem Renaissance was unequivocally important for the queer community, as well. The movement included racial acceptance but also extended further to encapsulate a welcoming exploration of gender and sexuality.

Within the Harlem Renaissance, theatres, hotels, lodgings, and bars comprised the physical context: places where individuals could “be free, not merely to express anything they feel, but to feel the pulsations and rhythms of their own life.”2 These buildings gave space to the queer community and welcomed populations that found solace amongst individuals of shared marginalized identities. Despite their importance throughout history, however, these spaces are invisibilized and have since been forgotten, destroyed, and disappeared. The loss of these places is not just a spatial transformation of the predominantly marginalized African American community, but a disappearance of historic safe spaces and queer memory within Harlem and the rest of New York City as a whole.

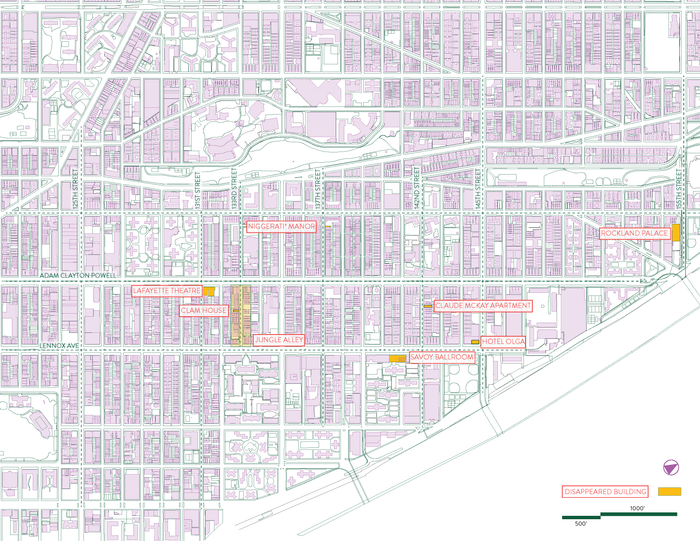

We, the authors, have chosen the disappearing queer spaces within Harlem as our topic of discussion. Places that identify an entangled history of queer people of color; a group that has been marginalized throughout time, and deserves to have their stories told and spaces memorialized. Acknowledging this reality, our research documents seven key queer spaces from the peak of the Harlem Renaissance in New York City. Spaces that disappeared over time due to processes of urban renewal, ownership changes, and gentrification. The seven sites will serve as case studies for our analysis. Each place will be cataloged individually in order to recreate a panorama of demolished and dilapidated buildings, which once activated and housed queer life in Harlem. The analytical focus will be on (1) the contextual situation of the place, (2) each space’s significant characteristics and function during the era, and (3) their discontinuation and decay. At the very core of this study, we hope to identify the reasons behind the demolition of these queer spaces and understand how queer erasure, gentrification, and marginalization played a role in the transformation of these sites.

Our analysis and findings will hopefully help prevent the future destruction of historic queer and cultural sites. Through this particular effort, we aim to begin a conversation about queer spaces that have disappeared and invoke an urgency to take action, think, remember, memorialize, and preserve future queer spaces at risk of similar fates.

Sincerely,

QSAPP

Vogel, Scene of Harlem Cabaret.

Wilson, Bulldaggers, Pansies, and Chocolate Babies.

1

Hotel Olga

Hotel Olga 1925

Apartments 1980

Unoccupied 2019

Empty Lot 2022

PLACES AND NEIGHBORHOOD CONTEXT

The Hotel Olga on Lenox Avenue and 145th Street was first built and used as the North End Hotel from 1898 to 1912; it then changed owners and names to the Dolphin Hotel in 1919.1 In 1920, when around 500,000 African Americans lived in Harlem, businessman Ed H. Wilson opened a small hotel expressly for Harlem’s African-American clientele.2 The renamed Hotel Olga’s activities were published periodically in papers across the country, attracting a variety of guests and incentivizing Black tourism in Harlem. In an era when Harlem’s infamous Hotel Theresa loomed as a citadel of racial exclusion, Hotel Olga served a critical use: a safe destination for Black individuals. Its feature in Victor Hugo Green’s Negro Motorist Green Book bolstered its status as a noteworthy destination and furthered the hotel’s reputation.3 For a quarter-century, spanning the storied Harlem Renaissance, the Great Depression, and World War II, Wilson’s venture offered Black travelers a key waypoint in America’s most renowned Black community.

SPACES

Designed by architecture firm Neville & Bagge, the hotel was a 3-story building with 40 rooms, lounge space, a library, and reading rooms. Signage played a large role in the building’s identity. A large extended banner announced the entrance to the hotel lobby and displayed the hotel’s name. Throughout all the name changes, the signage was updated. Yet, when the space no longer served as a hotel, the banner was removed.

ACTIVITIES

The Hotel Olga owner, Ed H. Wilson, was the brother-in-law to heiress A’Lelia Walker, prominent queer ally and daughter of Madam C.J. Walker. Walker would host a plethora of parties at her home and famous salon located in Harlem. Coined “The Dark Tower,”4 it was welcoming to many queer writers, musicians, and artists at the time.5 Between Wilson and Walker led many queer artists of the Harlem Renaissance to utilize Hotel Olga as a safe haven and respite. The individual rooms were places of artistic ideation and creation, while the lounges, library, and reading rooms would host conversations amongst queer guests.

PEOPLE

Many people of the artistic and bohemian world of the queer Harlem Renaissance periodically visited and stayed for entire seasons at the Hotel Olga. Among them, the iconic bisexual “Empress of Blues,” Bessie Smith, was a frequent guest of the hotel. Bessie Smith’s musical impact unequivocally inspired a generation of blues and jazz musicians that succeeded her.6 Alaine Locke, known as “the dean of the Harlem Renaissance” and the first Black American to be awarded the Rhodes scholarship, notably stayed at the Hotel Olga in May 1924. Locke, whose sexuality was no secret among his contemporaries, greatly influenced his peers with his contributions to Black art, culture, and society.7

DECAY AND DEMOLITION

Hotel Olga was not immune to the financial and social hardships that plagued New York in the 1960s and the state of the hotel –briefly apartments and retail– continued to decay until its eventual demolition in 2019. Design and development firm RPG introduced plans for a two-tower, mixed-use development called “One45” on the former site, which is set to include office, retail, residential, community space, and an area for the Museum of Civil Rights. However, in February 2022, the Manhattan borough president Mark Levine issued a recommendation to the city that the development be rejected, pending changes to improve the affordability of the project.8 As of now, the future of the site remains uncertain.

NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project, “Hotel Olga.”

O’Brien et al., “The Hotel Olga.”

O’Brien et al., “The Hotel Olga.”

Walser, “A’lelia Walker and the Dark Tower.”

Ryan, “Remembering A’Lelia Walker.”

Thompkins, “Forebears.”

Ryan, “Remembering A’Lelia Walker.”

Garber, “Harlem’s one45 Project.”

2

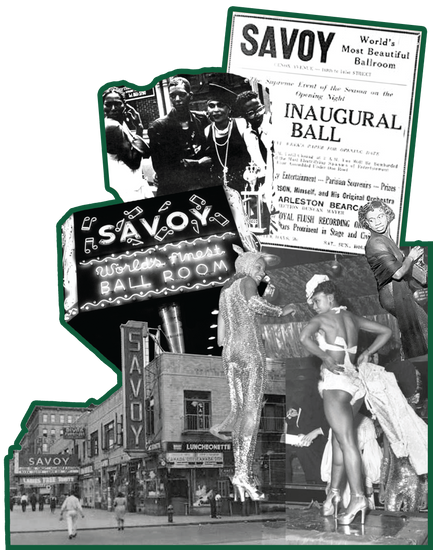

Savoy Ballroom

Savoy Ballroom 1926

NYCHA Apartments 1959

PLACES AND NEIGHBORHOOD CONTEXT

The Savoy Ballroom was a legendary dance hall on Lenox Avenue between 140th and 141st Streets in Harlem, New York. It was known as “The World’s Finest Ballroom” and “Home of Happy Feet.” From 1926 to 1958, its twin bandstands showcased the world’s finest jazz musicians.1

Opened in 1926, owner Moe Padden was accepting and welcoming to the queer subculture. The ballroom was located near Jungle Alley, a cluster of clubs in Harlem. Other clubs included Connie’s Inn, Barron’s, Lenox, and Lafayette Theatre, among others. In between the alley, the Savoy Ballroom was characteristic for welcoming Black and interracial audiences. According to Norma Miller, it was the first place in the world that Blacks and Whites walked through the door together.2

SPACES

The Savoy was a two-story ballroom, with the entry leading downstairs to the main floor. It had two bandstands, colored spotlights, and a rectangular dance floor (coined “the track”) that was over 10,000 square feet of spring-loaded wood. It had a capacity for 4,000 to 5,000 people, typically 85% Black and the other 15% White. In the 1930s the cover charge was between $0.30 to $0.85.3

ACTIVITIES

The Savoy Ballroom used to be a venue for Jazz and Swing music, typically drawing an interracial audience. The space was also home to some of the most prominent drag balls in New York City, a crucial event for the building of queer culture and identity within the community. Notably, the ballroom allowed guests to stay as late as 5 a.m. to protect their patrons from racist or homophobic attacks during the night.

The theatrics of the drag balls enhanced the solidarity of the queer world and symbolized the continuing centrality of gender inversion to queer culture.4 The balls literally put the queens in the spotlight. At one of these performances, Carl Van Vechten joined writer Muriel Draper and painter Bob Chanler in awarding first prize to a young man described as “stark naked, save for a decorative cache-sec and silver sadals, and …painted a kind of apple green.”5

PEOPLE

As mentioned, Carl Van Vechten, Muriel Draper, and Bob Chanler used to frequent the Savoy Ballroom, where they served as debutantes for different acts during the shows.6 The term debutante came from France when ballrooms were organized for aristocratic daughters to enter into society. Later, the term was used to refer to the concept of coming out.7 The queer community was actively involved in the Savoy Ballroom, both performers and spectators. In terms of queer patrons, it is documented that prominent artists such as Countee Cullen and Richard Bruce Nugent also frequented the space.

DECAY AND DEMOLITION

The Savoy Ballroom operated from 1926 until 1958. By the 1950s, the Harlem Renaissance, and interest in the drag balls, waned and the ballroom itself saw a downturn in patronage. The owner sold the property and the building was demolished to make way for the Savoy Apartments, which were eventually acquired by NYCHA. A plaque can be seen at the site today, but it makes no mention of the queer legacy or cultural role the Savoy Ballroom played during the Harlem Renaissance.

Marceau et al, “About the Savoy Ballroom.”

Marceau et al, “About the Savoy Ballroom.”

Marceau et al.

Chauncey, Gay New York, 297.

Chauncey, Gay New York, 298.

Chauncey, 7-8.

Chauncey, 7-8.

3

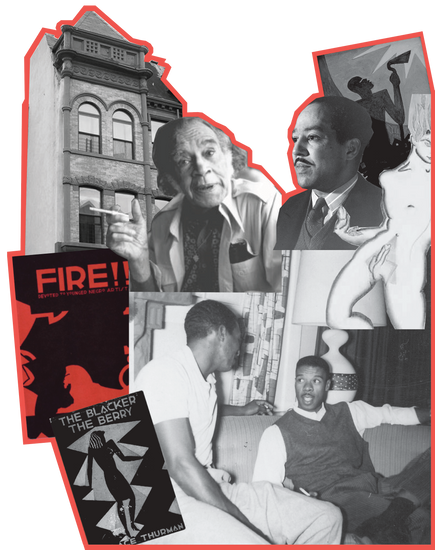

Niggeratti* Manor

*In scholarly texts, the Manor has been referenced with the spelling as “Niggerati” and “Niggeratti.” To simplify, we will use “Niggerati” throughout the text.

Niggerati Manor 1926

New Housing 2000

PLACES AND NEIGHBORHOOD CONTEXT

On 267 West 136th Street, near St. Nicholas Park, lies the lost brownstone for the literati. The manor’s title arose as “‘Niggerati’—a combination of the terms ‘literati’ and the derogatory ‘nigger’” which was purposely created for both a shocking and humorous effect by the group.1 As an enlightened cooperative enclave, the residents of the manor bestowed this title on themselves, supposedly created by Zora Neale Hurston, who affectionately “proclaimed herself ‘Queen of Niggerati.’”2 The townhome’s Black female owner, Iolanthe Sydney transformed the space when she allowed a group of literary and visual artists to live in her building for free, or at a drastically reduced price. Sydney wanted the artists to fully devote themselves to their work, without the burden of worrying about rent or income to hinder their endeavors.3

SPACES

Forensic architecture and historical photographs suggest Niggerati Manor was similar to the taller brownstones of Harlem, with unique fenestration, a front porch, and an elevated first level with a total of five floors. The interior of the brownstone is assumed to be of a similar layout to many current Harlem townhouses on the market today. Individual units in the townhome were leased out as SROs (Single Room Occupancy) for various residents, and interior spaces were used as dual living and working quarters.4 Furthermore, spaces of the manor were used for small parties, literature discussions, or as salons.5

ACTIVITES

The manor was an eccentric artist’s studio. Richard Bruce Nugent used interior walls as canvases, painting large erotic murals and multiple, bright phalluses, all presumably lost since the demolition.[6] It is also known that some interior walls were painted the same Black and brazen red color scheme as Langston Hughes’s FIRE!!, which was created at the townhouse; it was a nonconformist publication for young Black artists, issued only once, and meant to shock “respectable Black folk concerned with image.”6 Others wrote various novels from their experiences living there. It is said the setting in the novel Infants of the Spring by Wallace Thurman was based on the brownstone.7

PEOPLE

Langston Hughes, whose sexuality has been extensively discussed posthumously, was a pivotal figure of the Harlem Renaissance, whose contributions cannot be overstated. His body of work and legacy inspired swaths of Black writers in the 1950s and beyond.8 Richard Bruce Nugent, while not the most well-known figure of the Harlem Renaissance, notably addressed his queer identity in his writing and operated within Hughes’s circle of contemporaries.9 Wallace Thurman, a roommate of Nugent, founded, managed, and edited several Black magazines during the 1920s and often critiqued the work of other Renaissance scholars. Thurman’s sexuality undoubtedly manifested throughout his work as a writer, scholar, critic, and artist.10 Other well-known figures were said to have stayed at “Niggerati Manor,” including straight allies like Zora Neale Hurston and Aaron Douglas.11

DECAY AND DEMOLITION

The end of the enclave’s residency is alluded to in Thurman’s novel Infants of the Spring, where scholars discuss how the characters’ home is eventually shut down when the “landlady” (a possible stand-in for Sydney) “no longer believes in the financial security of art,” and thus changes the townhome into a “tenement for young women.”12 The building was demolished in the 90s, “the city was forced to tear down the storied dwelling after a contractor accidentally damaged it during a nearby demolition.”13 By 2000, retired police officer Angelo Ruotolo bought the auctioned lot.14 Today a smaller, unadorned red brick rowhouse stands in the former manor’s place.

Taborn, “The New Negro Movement.”

Pierpont, “Zora Neale Hurston, American Contrarian.”

Popik, “The Big Apple.”

Terrell Scott Herring, “The Negro Artist and the Racial Manor.”

Perrée, “Portrait of a Friendship 4: Wallace Thurman and the Niggerati.”

Perrée.

Perrée.

Vogel, “Closing Time.”

Samuels, “Richard Bruce Nugent (1906-1987).”

Ganter, “Decadence, Sexuality, and the Bohemian Vision.”

Heller and Ballance, Graphic Design History.

Hoffman, “Artist and the Folk.”

Tobias Salinger, “Langston Hughes Sites Don’t Display Legend’s Harlem Legacy.”

Salinger, “Langston Hughes Sites.”

4

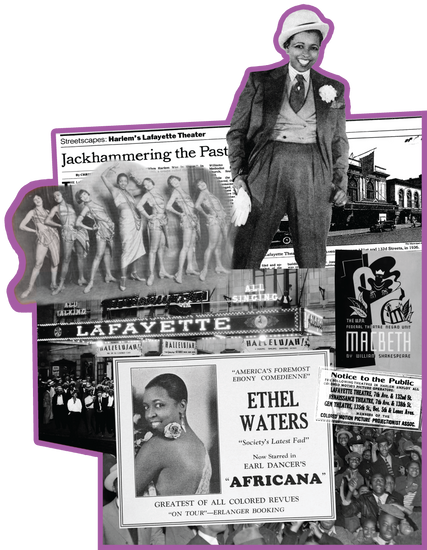

Lafayette Theatre

Lafayette Theater 1912

Church 2013

PLACES AND NEIGHBORHOOD CONTEXT

The Lafayette Theatre was located at 132nd Street and 7th Avenue (now Adam Clayton Powell Jr. Boulevard) in Harlem.1 Outside the building, and close to Connie’s Inn, was the Tree of Hope: an Elm tree that was supposed to give luck to the performers who touched it before going on stage. Eventually, the tree was cut into pieces and sent to different theatres. One piece famously resides in the Apollo Theatre today.2

SPACES

Lafayette Theatre was a two-story building, with three-story buildings flanking it between 131st Street and 132nd Street. Victor Hugo was the architect in charge of the theatre’s construction, which was designed in a Renaissance style. It opened in November 1912 as a theatre, cinema, and space for vaudeville performances, with a capacity of 1,500 guests.3

ACTIVITIES

In 1913, Lafayette became the first major theatre to desegregate. From 1916 to 1919, when it was managed by Quality Amusement, owner Robert Levy was successful at attracting large mixed audiences and hosted productions performed by Black actors, which was revolutionary at that time.4 Likewise, this theatre was famous for specifically accommodating the local Black community in times when segregation in Manhattan theatres (like those on Broadway) was common. One of the landmark performances was Anita Bush’s “The Lafayette Players” which ran from 1915 until 1932.

PEOPLE

The theatre attracted figures like the aforementioned Anita Bush (a pioneer in African American theatre), who defied notions of the time period that confined Black people to roles as singers, dancers, or slapstick comedians.5 Other notable queer performers included Bessie Smith and Ethel Waters.6 Bessie Smith, the “Empress of the Blues,” was known to sing without a microphone and speak truths of real-world struggles that shook audiences.7 It is noted that Ethel Waters performed in 1919’s “Hello, Alexander,” at the Lafayette Theatre and influenced audiences on the stage, and throughout Harlem, during her illustrious career.8 She was also well known in the lesbian community, although closeted to protect her Broadway and blues singing career. Moreover, it was noted by her friends that she lived with her girlfriend, dancer Ethel Williams and folks referred to them as the “two Ethels.”9 Queer artists, especially these controversial stars, played a large role in attracting audiences to the Harlem Renaissance and perpetuating the culture of the period.

DECAY AND DEMOLITION

The building operated as a theatre from 1912 to 1953. After the Harlem Renaissance ended in the 1930s, the Theatre was briefly closed, until eventually re-opening under the supervision of John Houseman of the Negro Theatre Group. Under his leadership, the theatre thrived and produced successful content until 1939.10 In 1951, the Williams Institutional Christian Methodist Episcopal Church acquired the building (Williams CME), and in 1990 the facade was replaced, angering the Lafayette Theatre community. In 2013, the structure was demolished. Today, construction for an 8-story apartment complex is currently underway.11

Gray, “Streetscapes: Harlem’s Lafayette Theater.”

Cass, “The Lafayette Theater.”

Apruzzese, “Lafayette Theatre.”

Kissinger, “The Lafayette Players (1915-1932).”

Cass, “The Lafayette Theater.”

Andrews, “The Lafayette Theater in Harlem.”

Thompkins, “Forebears.”

“Ethel Waters,” John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts.

Bourne, Ethel Waters: Stormy Weather.

Gray, “Streetscapes: Harlem’s Lafayette Theater.”

Andrews, “The Lafayette Theater in Harlem.”

5

Rockland Palace

Rockland Palace 1920

Skating Rink 1970

Parking Lot 2000

PLACES AND NEIGHBORHOOD CONTEXT

At the corner of 155th Street and Frederick Douglass Avenue, there was a sought-after venue that offered a haven for queer spectators and performers from all corners of New York City. The history of this building runs parallel to the history of the Harlem Renaissance, prohibition, the Great Depression, and more. In its lifespan, the space was inhabited by a wide array of figures, from celibate Christians to drag queens, showcasing its extraordinary place in Harlem history.

SPACES

The Rockland Palace was a Romanesque-style theatre building that housed a grand event space for political rallies, sermons, banquets, sporting events, roller rinks, concerts, and extravagant drag balls. The space itself consisted of a large auditorium with a stage and an overlooking balcony. Depending on the function, its configuration could accommodate rows of chairs, dining tables, or anything in between.

ACTIVITIES

Before it was renamed the Rockland Palace in 1928, the space was called the Manhattan Casino and served as an important location for sports culture.1 Additionally, the Hamilton Lodge, a chapter of the Grand United Order of Odd Fellows, hosted drag formals and balls at the Rockland Palace during the 1920s and 1930s.2 The extravagant events were a haven for the area’s LGBTQ community, drawing in people from Harlem and the U.S. at large. The dance was known simply as the “Faggots’ Ball,” and attracted up to 8,000 dancers and spectators at the height of its popularity. The Committee of Fourteen, a moral reform and religious organization, investigated the drag balls and subsequently released a 130-page book detailing the ‘scandalous behavior’ they witnessed, yet did little to prevent the annual event.3 If one missed the ball, they could find detailed accounts given through the Black press and Broadway gossip channels. The publications were early accounts of queer life, documenting well before the Stonewall riots and showcasing how integral the events were for queer social life in New York City.

PEOPLE

Leading figures of the Black community were often spectators at Rockland Palace, while the queer community both participated and observed. Langston Hughes described events at the Palace, recalling that “during the height of the New Negro era and the tourist invasion of Harlem, it was fashionable for the intelligentsia and the social leaders of both Harlem and the downtown area to occupy boxes at this ball and look down from above at the queerly assorted throng on the dancing floor.”4 Key queer and allied spectators included writers Wallace Thurman, Bruce Nugent, and the heiress socialite A’Lelia Walker. Additionally, revered gay celebrities including Tallulah Bankhead, Beatrice Lillie, and Clifton Webb, all made their way from downtown Manhattan to Harlem for the balls.

DECAY AND DEMOLITION

At the close of the Harlem Renaissance, the Rockland Palace continued to host a variety of other political, spiritual, and musical events. By the 1970s, concert halls were all but extinct as newer forms of music production and distribution were formalized. The Rockland Palace was then converted into Rooftop Roller Skating and Disco. The conversion was simple, considering the large, spacious ground floor and the building itself continued to serve as a cultural hub for the local community.5 In the 1980s, with an increase in crime throughout the city and especially within Harlem, the roller rink fell victim to various murders that led to the site’s eventual closure.6 During the 1990s, with a lack of function and perpetual neglect, the building was demolished to make way for a parking lot.

Harlem World Magazine, “The Rockland Palace Dance Hall.”

Barga, “Grand United Order.”

Harlem World Magazine, “The Rockland Palace Dance Hall.”

Harlem World Magazine, “The Rockland Palace Dance Hall.”

Brewington, “Rooftop Roller Skating Rink.”

“2 Men Killed and Girl Is Wounded Near Rink,” New York Times.

6

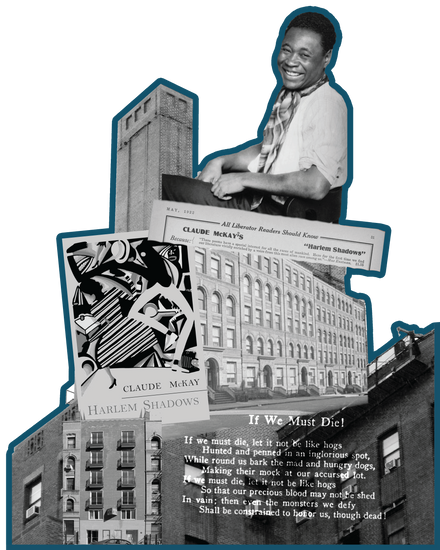

McKay Apartment

Claude McKay Apartment 1920

Apartments 2005

PLACES AND NEIGHBORHOOD CONTEXT

The apartment of Claude McKay was located at 147 West 142nd Street, adjacent to 7th Avenue. It was a crucial space for both the development of the queer scene in Harlem and the identity of the Black middle class of Harlem and abroad. The space was denoted as a “Cabaret School” where Claude McKay performed as a host and instructor.1 McKay was a person who, with the interventions housed in his apartment, challenged, “the calcification of racial and sexual identities and the use of those identities in strategies of social order and control by dominant White society as well as by the ideologies of normative life.”2

SPACES

The segment of 142nd Street where the building is located reflects a classic New York City apartment block, with one-way streets lined with brownstones and row houses. Amendments to the tenement law in 1919 enabled the division of single-family row houses into multi-unit housing, which altered how these structures housed individuals. For artists and bohemians in Harlem during the 1920s, rent parties were a norm and an instrumental element of the arts, culture, and queer scenes of Harlem at that time.3 Claude McKay frequented others’ rent parties as well as having his own.4 They raised money to cover rent costs by charging admission to social, musical, and artistic events hosted within the apartment.

ACTIVITIES

In his apartment, McKay rethought theories surrounding gender, sexuality, and race often with his peers. He was particularly interested in challenging stereotypes and the ongoing perception of racial and sexual identity. All of these ideas directly influenced his art practice and published work, productions that took place directly in his apartment. Claude McKay’s liberal and avant-garde ideas ended up influencing spatial conditions and performances, as he created “enactments of emergent alternative sociality.”5 McKay would utilize the space to host guests, in order to keep conversations going.

PEOPLE

The central force of this space was the poet and performer Claude McKay. His 1928 fiction, “Home to Harlem,” is notable as it depicts the histories and landscapes of the Harlem Renaissance, including an openly gay character. He is applauded by many for his depictions of Harlem as “an elaboration of shared affect that is organized by the architecture and sociality of a performance space.”6 To the queer community, McKay was also free with his sexuality throughout all spaces in the Harlem Renaissance. His 1922 poetry book “Harlem Shadows” even includes queer subtext, which led the FBI to title it a “collection of radical poems” written by “a notorious negro revolutionary.”7

DECAY AND DEMOLITION

Little is documented as to when McKay moved out of this particular space, but the harassment he faced at the hands of the FBI played a role in him leaving America. The apartment building existed until 2004 when it was demolished and replaced with new housing, whose average rent has increased by 32% in the past 10 years.8

Vogel, The Scene of Harlem Cabaret, 19-20.

Vogel, The Scene of Harlem Cabaret, 19-20.

Byrd, “Harlem Rent Parties”.

Griffin, Fragmented Vision of Claude McKay.

Vogel, The Scene of Harlem Cabaret, 160.

Vogel, The Scene of Harlem Cabaret, 156.

Alison, “FBI monitored and critiqued African American writers.”

“147 West 142nd St. in Central Harlem,” StreetEasy.

7

Clam House

Clam House 1928

Apartments 1990

PLACES AND NEIGHBORHOOD CONTEXT

Jungle Alley, 133rd Street in Harlem, was a cluster of clubs, ballrooms, venues, speakeasies, and spaces dedicated to nightlife, music, dance, culture, and entertainment. Beginning in the 1920s with the Harlem Renaissance, this locally activated area also became a tourist destination for both the White and Black community throughout the nation, having been described as the “epicenter of [the Renaissance’s] thriving nightlife.”1

SPACES

As part of the network composing the Jungle, important cultural spaces included Barron’s Exclusive Club, Connor’s, Bill’s Place, Cotton Club (formerly The DeLuxe), and Connie’s Inn. One of the most renowned spaces was Edith’s Clam House (also known as Harry Hansberry’s Clam House or Gladys’ Clam House). Having opened in 1928 at 146 West 133rd Street, it was considered one of the most important speakeasies on the block due to Gladys Bentley, who could be found “performing in a signature white top hat, tuxedo and tails, [singing] raunchy songs laced with double-entendres that thrilled and scandalized her audiences.”2 Similar to the other speakeasies on 133rd Street, the upper floors of the brownstones were residential, while the ground floors or basements were used for retail and bars. Signage played a significant role in identifying the commercial nature of these lower floors and announcing to the public that these spaces existed, as exemplified by the Clam House overhang.

ACTIVITIES

This alley was primarily a nightlife district with a variety of different places, such as speakeasies, clubs, and bars. This district was a place where queer individuals, Black individuals, and those of other intersectional identities could experience authentic culture inside one of the most iconic and transcendent places in Harlem. Gladys Bentley was the star of the Clam House, performing throughout the 1920s. Her productions featured blues singing and playing piano, in addition to cross-dressing and drag queen backup dancers; these performances garnered the Clam House the title of the “most swinging gay uptown establishment.”3 The activities and spatial configurations of Clam House can be seen replicated across Jungle Alley, which also welcomed and celebrated a thriving queer community.

PEOPLE

Gladys Bentley–with a signature top hat and tailcoat suit–is best remembered for pushing the limits of race, sexuality, and class through her raunchy blues performances within New York City nightclubs.4 The singer and pianist’s preference for women is well-documented, as her performances incorporated sexual elements uncharacteristic of the time. She performed at clubs and venues throughout Harlem and Jungle Alley, especially the Clam House which many believed she owned for some time.5

DECAY AND DEMOLITION

Over time, many of the places in the Alley started to disappear. Many spaces got demolished and replaced by new developments, houses, or offices.6 Similarly, prohibition caused several clubs to relocate or close altogether, creating a decaying strip of clubs and nightlife. Other buildings in Jungle Alley, like the Cotton Club, are still in operation but do not resemble what they looked like during the Harlem Renaissance. The Clam House, later renamed Covan’s under new ownership, was demolished in the 1960s.7 The building was replaced with a new apartment building in 1990, during the surge of rapid gentrification of the city.

Wilson, Bulldaggers, Pansies, and Chocolate Babies, 44.

Shah, “Great Blues Singer Gladys Bentley.”

Gill, “Meet Gladys Bentley.”

Anders, “Gladys Bentley (1907-1960).”

Shah, “Great Blues Singer Gladys Bentley.”

Kiernan, “Jungle Alley.”

Liu and Lechtzin, “80s.NYC - Street View of 1980s New York;” Kiernan, “Jungle Alley.”

8

Analysis

OVERVIEW

The Harlem Renaissance cultivated a safe space for queer people of color and helped develop a rich culture of influence. Spatial configurations of the neighborhood fostered a thriving community for a population of people that were historically outcasted. The case studies ranged in their size and stature, but freedom of expression was integral to each. Despite their importance, all of the places have been lost to physical demolition and are disappearing from social memory.

This chapter will highlight the precedents and socio-political factors that affected their change. (1) We begin with identifying limitations that the queer community and their related spaces face, which ranged from legal, to physical, to experiential discrimination; and (2) through our analysis, we will discuss causes that have led to the disappearance of the spaces, and posit overall cultural and spatial shifts that impacted queer Harlem.

QUEER SPATIAL LIMITATIONS

People within the queer community faced continuous limitations, and their subsequent spatial surroundings were not immune. The individuals themselves often faced legal and physical restrictions on who they could marry, how they could behave, and how they could interact with one another. Experientially, they also faced harassment and surveillance, should their queer identities be revealed whether through their art or actions.1

Spaces, in which the community occupied, including those in this book, faced similar limitations both legally, physically, and experientially. Clubs and bars that were caught with homosexual couples dancing saw their liquor licenses revoked. Police raids and padlocked entries were alternative physical barriers imposed, because of gay venues that would play ‘dirty songs’ which had homoerotic subtexts.2 Other places were demolished due to ever-increasing urban renewal and gentrification efforts.3 Ultimately, a combination of limitations, both on bodies and spaces, restricted the queer culture and community of the time, which affected its dissolution in Harlem after the Renaissance was over.

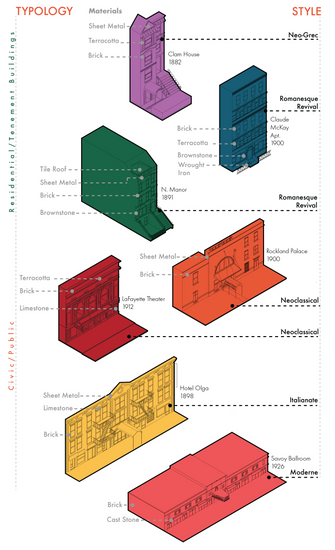

STYLES AND TYPOLOGIES

While the buildings acquiesced to their surrounding styles and contexts, the interiors were activated by the queer community, defining queer culture. The building’s styles were common and typical for the Harlem area. Some were residential or hospitality, others occupied individual floors or were freestanding. In instances of the Clam House, Claude McKay’s Apartment, and the Niggerati Manor, the buildings were exact replicas of those around them. From Neoclassical to Italianate, to Romanesque Revival, the building styles blended into the area, yet masqueraded their queer insides. Late into the night, houses, ballrooms, and theatres hosted the community, where individuals gained visibility and transformed the venues into elegant events. Even though they were not intentionally constructed as queer spaces, all of the buildings were a part of the culture. The spatiality of the buildings and the bodies that interacted and activated them are entangled with the queer identity.

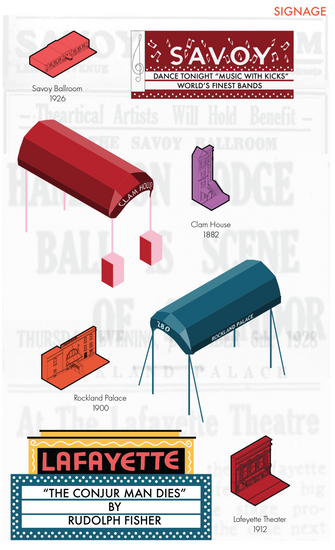

SIGNAGE AND VISIBILITY

Another important factor shared by these queer spaces is their inherent visibility to the Harlem community. Among the buildings, signage played a critical role in demanding visibility and branding identity. The Clam House was within a sea of brownstones and its signage announced to visitors of Jungle Alley that the space existed. The facades, specifically the device of the signage, functioned as a medium for managing visibility and decoding the neighborhood for users.

For other spaces, their connection to queer people was through newspaper articles and flyers for upcoming events, such as drag balls and performances by queer artists. Often after events occurred, documentation of their existence in mainstream media was noted. A New York Age article from 1930 reads, “Hamilton Lodge Ball is Scene of Splendor; Rockland Palace is Rendezvous for the Frail and Freakish Gang.”4 That expressionistic visibility could not as easily be afforded to the individual: some queer artists were closeted and others were out. Instances where people, like Claude McKay, faced the possibility of harassment and surveillance. The curation of queer visibility through signage, media, and other technologies functioned as risk-averse modes of communication that connected the community to the spatial conditions we highlighted through the case studies. These technologies worked together to escape the control of limitations by governments, and law enforcements through subversive tactics that queer the architecture itself. Thus, the signage and visibility of the buildings, and their media coverage, were critical to their function and identity.

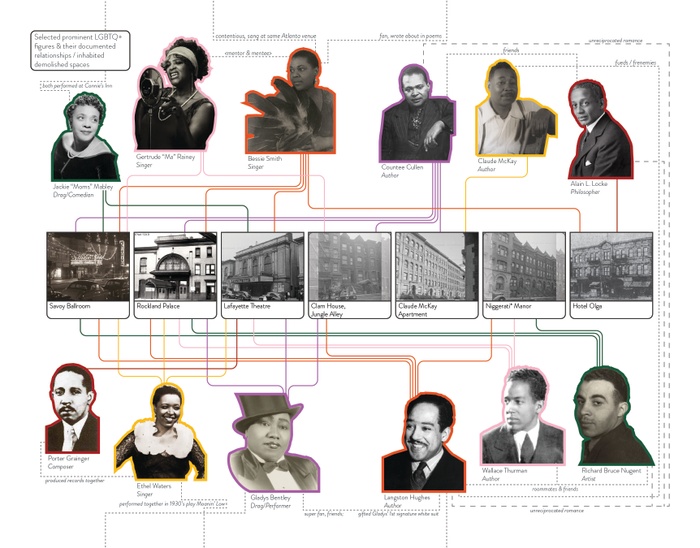

Queer Harlem Community

The queerness of the Harlem Renaissance relied as much on the people that occupied the places as they did on the activities inside. Identifying key queer individuals who participated in the Harlem Renaissance, and their spaces of occupation, illustrated that there was a thriving queer community that utilized the case studies and other buildings throughout Harlem.

Even when faced with limitations such as cabaret laws, revoked liquor licenses, surveillance, police raids, and padlocks, the queer community managed to persevere and activate Harlem in a unique way. Diversified typologies from nightclubs, to rent parties, to cafe conversations, to drag balls allowed the community to prosper within the Harlem Renaissance, generating a new subculture.

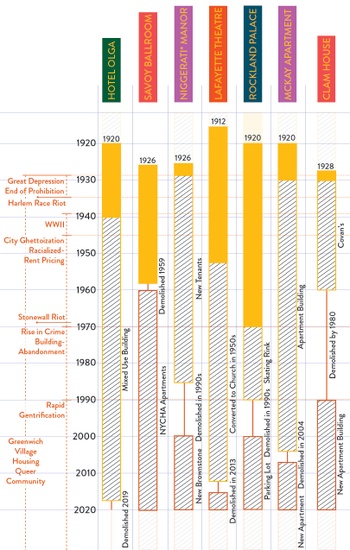

TIMELINE

However, just as the Harlem Renaissance came to an end during the 1930s, so did the habitation of the queer spaces. Factors of racialized rent pricing, property abandonment, and the general economic posture of the past century all contributed to the disappearing buildings. By the 1930s, the Great Depression and the end of prohibition were bringing the Harlem Renaissance to an end.5 Additionally, with the Harlem Race Riot of 1935, there were decreasing numbers of White people in Harlem and an increase in racialized stereotypes about the neighborhood.

Between the 1930s and 1950s, with decreasing demand for large venues to host balls and parties, queer spaces were either converted into new uses or torn down altogether. At the same time, Greenwich Village (a neighborhood in southwest Manhattan) was becoming the new hub for the queer community, with a plethora of queer-friendly nightclubs and bars, and artists residing there. By the 1990s, Harlem began facing rapid gentrification by new developers. Queer spaces were not resistant to such reconstructions.6 As noted in the timeline, there is a wide variation between re-occupancies and demolition of the studies, but there is a common thread of disappearance both physically and mentally.

CONCLUSION

Architecture is entangled in devices and technologies: from bodies to signs, to fashion, to music, to newspapers, to paintings. These devices all work together to construct a broader definition of architecture as an ability to become activated and nurture culture and community. The queerness of the Harlem Renaissance was not shackled to architectures or institutions but instead subverted power dynamics through all of these devices working together. The result curated a visible culture and created safe atmospheres for those with marginalized identities to prosper.

The queer community has faced limitations, harassment, and obstacles for the vast majority of human history. The disappearance of these queer spaces and stories from the Harlem Renaissance is no different. Not only have the physical conditions been destroyed, but the histories and memories of these spaces are few and far between. The purpose of this book is to amplify queer histories and spaces to render them visible, despite their erasure.

The queer community played a substantial role in the Harlem Renaissance having its own thriving subculture. Despite this, the documentation and preservation of these stories and spaces are much less than their heteronormative counterparts. The individuals that contributed most to art in the Harlem Renaissance were queer people of color. It is imperative that their historical erasure halt here. Although the seven case studies are gone, they are only the tip of the iceberg. It leaves one to ponder the stories not documented or remembered at all; stories that are just as worthy of memorialization. Similarly, the spaces that are left are still threatened by the ever-present societal apathy and looming rapid gentrification of the cityscape.

Today, we acknowledge and memorialize the Harlem Renaissance, through plaques recalling past buildings or historic preservation. However, the queerness of the Harlem Renaissance and the people and places that make up its history is being erased from common memory. Thus, marking the importance of this book: to embrace and remember queer histories, peoples, and spaces, even if the rest of the world does not.

We, the authors, challenge this generation of queer doers, and allies of all ethnic backgrounds, to foster their own enclaves of remembering, being, contemplating, partying, and creating. Sustain and celebrate your queer presence of today; protect it from becoming the disappearing queer space of tomorrow.

Alison, “FBI monitored and critiqued African American writers.”

Shah, “ Great Blues Singer Gladys Bentley.”

Columbia Libraries, “Stonewall and Beyond.”

Digital Transgender Archive, “Hamilton Lodge Ball.”

Davis et al, Documents of the Harlem Renaissance.

Gørrild et al, “Gentrification and Displacement in Harlem.”

Citations

“146 West 133rd St. in Central Harlem.” StreetEasy. Accessed March 29, 2022. https://streeteasy.com/building/146-west-133-street-new_york.

“147 West 142nd St. in Central Harlem.” StreetEasy, n.d. https://streeteasy.com/building/147-west-142-street-new_york.

“2 Men Killed and Girl Is Wounded Near Rink.” New York Times. February 2, 1989.

Anders, Tisa M. “Gladys Bentley (1907-1960).” Black Past, May 19, 2021. https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/bentley-gladys-1907-1960/.

Andrews, Stefan. “The Lafayette Theater in Harlem Became the First Major Theater Which Did Not Segregate African-American Audiences in New York.” The Vintage News, February 19, 2017. https://www.thevintagenews.com/2017/02/20/the-lafayette-theater-in-harlem-became-the-first-major-theater-which-did-not-segregate-african-american-audiences-in-new-york/?chrome=1&A1c=1.

Apruzzese, Pete. “Lafayette Theatre.” Cinema Treasures. Accessed March 28, 2022. http://cinematreasures.org/theaters/12596. Bayeza, Ifa. “Infants of the Spring: Disrupting the Narrative.” Scholarworks @UMassAmherst, 2018. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/masterstheses2/629.

Bourne, Stephen. Ethel Waters: Stormy Weather. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow P., 2007.

Brewington, Tanya. “Rooftop Roller Skating Rink.” Brewington Cloth. Accessed April 10, 2022. https://brewingtoncloth.com/collections/rooftop-roller-skating-rink-and-disco?msclkid=e7230d81b91b11ec929ab9e5097f4002.

Byrd, Frank. Harlem Rent Parties. New York City, New York, 1939. Manuscript/Mixed Material. https://www.loc.gov/item/wpalh001365/.

Cass. “The Lafayette Theater and Harlem’s Tree of Hope.” Harlem World Magazine, May 30, 2016. https://www.harlemworldmagazine.com/the-lafayette-theater-and-harlems-tree-of-hope/.

Chauncey, George. Gay New York: Gender, Urban Culture, and the Makings of the Gay Male World, 1890-1940. New York: Basic Books, 1994.

Columbia Libraries. 2011. “Stonewall and Beyond: Lesbian and Gay Culture.” Columbia University. http://www.columbia.edu/cu/lweb/eresources/exhibitions/sw25/case1.html.

Davis, Thomas J., and Brenda M. Brock. Documents of the Harlem Renaissance. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, An imprint of ABC-CLIO, LLC, 2021.

Digital Transgender Archive and JD Doyle Archives. 1930. “Hamilton Lodge Ball is Scene of Splendor.” The New York Age, February 22, 1930. https://www.digitaltransgenderarchive.net/files/6t053g18d.

Dion, Nahshon. “The Gay Trailblazer of the Harlem Renaissance: Biographer Jeffrey C. Stewart on Alain Leroy Locke.” Lambda Literary, July 10, 2020. https://lambdaliterary.org/2018/07/alain-leroy/.

“Ethel Waters.” Drop me off in Harlem. John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts. Accessed March 28, 2022. https://artsedge.kennedy-center.org/exploring/harlem/faces/waters_text.html.

Flood, Alison. 2015. “FBI monitored and critiqued African American writers for decades.” The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/books/2015/feb/09/fbi-monitored-african-american-writers-j-edgar-hoover?msclkid=e5ab827cb91511ec821eaa88b1ffef03.

Ganter, Granville. “Decadence, Sexuality, and the Bohemian Vision of Wallace Thurman.” MELUS 28, no. 2 (2003): 83. https://doi.org/10.2307/3595284.

Garber, Nick. “Harlem’s one45 Project Rejected by BP over Affordability Concerns.” Harlem, NY Patch. Patch, February 23, 2022. https://patch.com/new-york/harlem/harlems-one45-project-rejected-bp-over-affordability-concerns.

Gill, Jasica. “Meet Gladys Bentley: The Gender Non-Conforming Queen of the Harlem Renaissance.” WOMEN SOUND OFF, February 27, 2019. https://womensoundoff.com/blog/2019/2/23/gladys-bentley-a-black-non-binary-entertainer-who-dominated-during-the-harlem-renaissance.

Gørrild, Marie, Sharon Obialo, and Nienke Venema. “Gentrification and Displacement in Harlem: How the Harlem Community Lost Its Voice En Route to Progress.” Humanity in Action, n.d. https://www.humanityinaction.org/knowledge_detail/gentrification-and-displacement-in-harlem-how-the-harlem-community-lost-its-voice-en-route-to-progress/?msclkid=9772572ebac011ec90968a0d66ebd697.

Gray, Christopher. “Streetscapes: Harlem’s Lafayette Theater; Jackhammering the Past.” New York Times. November 11, 1990.

Griffin, Barbara Jackson. The Fragmented Vision of Claude McKay: A Study of His Works. Ann Arbor, MI: Univ. Microfilms Internat., 1989.

Harlem World Magazine. “The Rockland Palace Dance Hall, Harlem NY 1920.” Harlem World Magazine, October 27, 2015. https://www.harlemworldmagazine.com/the-rockland-palace-dance-hall-harlem-ny-1920/.

Heller, Steven, and Georgette Ballance. Essay. In Graphic Design History, 269–70. New York, NY: Allworth Press, 2001.

Herring, Terrell Scott. “The Negro Artist and the Racial Manor: Infants of the Spring and the Conundrum of Publicity.” African American Review 35, no. 4 (2001): 581. https://doi.org/10.2307/2903283.

Hoffman, Alexandra. “The Artist and the Folk: Politics, Identity and Humor in the Work of Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston, Sholem Aleichem and Mordkhe Spector,” 2012.

Kiernan, Matthew X. “‘Jungle Alley’, 133rd St., Harlem.” Flickr. Yahoo!, January 29, 2009. https://www.flickr.com/photos/mateox/3236833146/.

Kissinger, Michael. “The Lafayette Players (1915-1932),” December 23, 2020. https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/lafayette-players-1915-1932/.

Liu, Brandon, and Jeremy Lechtzin. “80s.NYC - Street View of 1980s New York.” Edited by NYC Department of Record. 80s.NYC - Street View of 1980s New York. Accessed March 29, 2022. http://80s.nyc/.

Marceau, Yvonne, and Jun Maruta. “About the Savoy Ballroom.” Mark the Savoy, n.d. http://www.savoyplaque.org/about_savoy.htm. NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project, “Hotel Olga, 8, 2022, https://www.nyclgbtsites.org/site/hotel-olga/.

O’Brien, Garrett, Post Editors, Jeff Nilsson, and Ben Railton. “The Hotel Olga: The Forgotten Home of the Harlem Renaissance.” The Saturday Evening Post, February 10, 2021. https://www.saturdayeveningpost.com/2021/02/the-hotel-olga-the-forgotten-home-of-the-harlem-renaissance/.

Perrée, Rob. “Portrait of a Friendship 4: Wallace Thurman and the Niggerati.” AFRICANAH.ORG, July 4, 2020. https://africanah.org/portrait-of-a-friendship-4-wallace-thurman-and-the-niggerati/?msclkid=2e39b9b8b91b11ec9494631eb3ebc1d2.

Pierpont, Claudia Roth, John C. Mosher, and Janet Flanner. “Zora Neale Hurston, American Contrarian.” The New Yorker, February 10, 1997. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/1997/02/17/a-society-of-one.

Popik, Barry. “Niggeratti Manor (267 West 136th Street).” The Big Apple. Accessed March 29, 2022. https://www.barrypopik.com/index.php/newyorkcity/entry/niggerattimanor267west136th_street.

Ryan, Hugh. “Remembering A’Lelia Walker, Who Made a Ritzy Space for Harlem’s Queer Black Artists.” NPR. NPR, September 22, 2015. https://www.npr.org/sections/codeswitch/2015/09/22/436344078/remembering-alelia-walker-who-made-a-ritzy-space-for-harlems-queer-black-artists.

Salinger, Tobias. “Langston Hughes Sites Don’t Display Legend’s Harlem Legacy.” nydailynews.com. New York Daily News, April 11, 2018. https://www.nydailynews.com/new-york/manhattan/langston-hughes-sites-don-display-legend-harlem-legacy-article-1.2106291.

Samuels, Wilfred D. “Richard Bruce Nugent (1906-1987) .” Black Past, September 4, 2019. https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/nugent-richard-bruce-1906-1987/.

Shah, Haleema. “The Great Blues Singer Gladys Bentley Broke All the Rules.” Smithsonian. Smithsonian Institution, March 14, 2019. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smithsonian-institution/great-blues-singer-gladys-bentley-broke-rules-180971708/.

Barga, Michael. “Grand United Order of Odd Fellows in America.” Social Welfare History Project, June 22, 2020. https://socialwelfare.library.vcu.edu/eras/grand-united-order-of-odd-fellows-in-america/.

Taborn, Karen Faye. “The New Negro Movement and ‘Niggerati Manor.’” Essay. In Walking Harlem: The Ultimate Guide to the Cultural Capital of Black America. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2018.

Thompkins, Gwen. “Forebears: Bessie Smith, the Empress of the Blues.” NPR. NPR, January 5, 2018. https://www.npr.org/2018/01/05/575422226/forebears-bessie-smith-the-empress-of-the-blues.

Vogel, Shane. “Closing Time: Langston Hughes and the Poetics of Harlem Nightlife.” Criticism 48, no. 3 (2008): 397–425. https://doi.org/10.1353/crt.2008.0004. Vogel, Shane. The Scene of Harlem Cabaret: Race, Sexuality, Performance. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, n.d.

Walser, Lauren. 2017. “How A’Lelia Walker And The Dark Tower Shaped The Harlem Renaissance.” National Trust for Historic Preservation, March 29, 2017. https://savingplaces.org/stories/how-alelia-walker-and-the-dark-tower-shaped-the-harlem-renaissance#.YlF2tMjMIuV.

Wilson, James F. Bulldaggers, Pansies, and Chocolate Babies: Performance, Race and Sexuality in the Harlem Renaissance. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2011.

Zane, Zachary. “Black and Queer in the Harlem Renaissance.” Queer Majority. Queer Majority, February 28, 2022. https://www.queermajority.com/essays-all/black-and-queer-in-the-harlem-renaissance.