About the Authors

QSAPP (Queer Students of Architecture, Planning, and Preservation) is a student organization at Columbia University’s Graduate School of Architecture, Planning, and Preservation (GSAPP) in New York City. We seek to foster both conversation and community among LGBTQ students, their allies, faculty, and alumni of GSAPP. We actively explore contemporary queer topics and their relationships to the built environment through an engagement with theory and practice. Founded in 2014, QSAPP has participated in and presented numerous events and projects, including Coded Plumbing, a project about gendered restroom design, a lecture by Joel Sanders, author of Stud: Architectures of Masculinity, and a symposium in honor of the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall Riots, Stonewall 50: Defining LGBTQ Site Preservation. This is QSAPP’s first publication.

QSAPP Team:

Dalton Baker (Chair), Tim Daniel Battelino, Daniel Mauricio Bernal, David Sheng Bi, Faraz Butte, Don Chen, Axelle Dechelette, Clifford DeKraker, Christine Giorgio, Andrew David

Grant, Matt Graves, Ruben Gutierrez (Chair), Kevin Hai, Jarrett Ley, Jared Payne, Gwendolyn Stegall (Chair), Alek Tomich, Brian Turner, Nelson De Jesus Ubri, Ian Wach, John Elihu Wofford

V, Francis Yu

For more information about QSAPP contact: qsapp.gsapp@gmail.com

Acknowledgements

Many people were instrumental to our research and bringing this publication to fruition. Thank you to Christine Hunter, AIA, LEED AP BD+C; Julie Chou, AIA of Magnusson Architecture and Planning PC; Carl Siciliano, executive director of the Ali Forney Center; and Steve Herrick, executive director of the Cooper Square Committee for their essential information and participation on our panel about the Bea Arthur Residence in March 2018. Thank you to Richard Froehlich, chief operating officer, executive vice president, and general counsel of the New York City Housing Development Corporation, and professor at GSAPP in the real estate program; and Theresa Cassano, director of the Supportive Housing Loan Program, NYC Department of Housing Preservation and Development for their information on affordable housing finance. Thanks to Emily Lehman, assistant commissioner of the Division of Special Needs Housing at HPD. Thank you to Jody Rudin, chief operating officer at Project Renewal, and to Geoffrey Proulx, chair of the board at Project Renewal and managing director at Morgan Stanley’s Municipal Housing Finance Group. Thank you to Lillian Rivera, Alayne Rosales, and Colton Fontenot of Hetrick-Martin Institute: New Jersey for information on HMI, including a valuable site visit. Thank you to Kahlib Barton, Michelle Blassou, Twiggy Pucci Garçon, and Christa Price of True Colors United for their nationwide perspective on the LGBTQ youth homelessness crisis.

Thank you also to the GSAPP administration for supporting this project, both financially and organizationally. Thanks to Lyla Catellier, director of events and public programs at GSAPP, who facilitated our panel on the Bea Arthur Residence last year and our publication release event. Thank you especially to James Graham, director of publications at GSAPP, for making possible the publishing and printing of this document. Thank you to Marie-Louise Stegall and Walter Ancarrow for proofreading the text, and thank you to Yoonjai Choi for her graphic design consultation.

Preface

This document presents QSAPP’s research into housing for LGBTQ youth experiencing homelessness in New York City. It is an interdisciplinary project looking at this issue from the perspectives of the various fields represented at GSAPP—architecture, real estate, planning, and preservation. We draw from a range of sources, including data from government and social service organizations, operating models of existing organizations in New York, and interviews with service providers and experts in the field. Almost all of the information we found on this topic was from the perspectives of sociology, public health, or advocacy. Funding is often cited as one of the biggest barriers to solving this housing crisis, but an analysis of funding models and strategies does not currently exist. In addition, housing is a design problem but there are no published reports that analyze LGBTQ youth housing from a spatial perspective. QSAPP hopes that by visualizing this issue and highlighting ways in which these shelters fit into specific planning and real estate systems in the city, we can further shed light on the specific needs of LGBTQ youth and help advise on ways forward with these concerns in mind.

Our intention in presenting this publication is also to make the design and development fields more aware of this urgent issue and highlight solutions that can be implemented to better serve the LGBTQ youth population. Topics that we discuss in our disciplines, such as housing typologies, real estate and funding models, zoning techniques and neighborhood involvement, as well as adaptive reuse strategies are all put through the lens of LGBTQ youth housing in this document. We examine the specific housing needs of LGBTQ youth, how the existing LGBTQ specific shelter spaces are configured and used, how they are funded, and how they connect to broader systems of the city. Through these questions, we highlight ways in which the architecture and design communities can engage with these issues. Our research is largely centered on the New York metropolitan area. The problem is particularly acute here since it is a large urban center to which many LGBTQ youth gravitate, but where the cost of living is prohibitively high. New York is exceptional; however, in the number of organizations focused on finding a solution to this problem, which enabled us to draw on existing models. Hopefully the lessons learned from New York City can be helpful to any community faced with this issue.

Introduction

There are many ways that youth come into homelessness and an equally large number of ways that homelessness manifests. The stories and experiences of each individual are unique and vary according to each person’s background and situation. LGBTQ youth are often the target of societal and familial stigmas surrounding their “non-normative” identity. These difficulties often push youth towards housing instability which often compounds existing insecurities and mental health issues. While sleeping on a subway train or on the street is the most common perception of homelessness, LGBTQ youth cope with this situation in many ways. Often, the first step in escaping an abusive or misapprehending home life is by living with friends and relatives. They are often an additional household member within an already tight living situation. These young people often couch surf between different homes, not having one stable place to stay long term. Some LGBTQ young people end up in the shelter system, though many prefer to stay on the street because of the poor conditions and homophobic or transphobic atmosphere at many of the available spaces. Not all LGBTQ young people end up homeless as a result of running away from home. Sometimes youth lack a support system entirely and become homeless after they age out of the foster care system or their families are unable to support them. These definitions are not mutually exclusive and youth often cycle from one situation to another.

The National Alliance to End Homelessness defines homeless youth as unaccompanied people between the ages of twelve and twenty-four with no familial support or permanent residency.1 The specific age bracket defined as “homeless youth” changes across the nation depending on local laws, and local organizations adjust their services and age cut-offs accordingly. New York City passed a bill in 2018 that allows people up to twenty-four years of age to remain in youth shelters (previously the cut-off was twenty-one), an important step in avoiding the especially problematic adult shelter system.2 While less than 10% of the United States youth population identifies as LGBTQ, this percentage more than doubles in the nationwide youth population currently experiencing homelessness.3 Although there is not an accurate nationwide count of homeless youth, it is estimated that between 1.3 and 1.7 million young people experience one night of homelessness a year and 550,000 young people are homeless for a week or longer.4 This means that, even by conservative estimates, there are at least 260,000 LGBTQ youth who will experience a night of homelessness this year, 110,000 of whom will experience longer-term homelessness. The percentage of youth who identify as LGBTQ as opposed to heterosexual doubles again for New York City — 40% of homeless youth in NYC are LGBTQ.5 An estimated 1,600 young people who identify as LGBTQ are currently experiencing homelessness in New York City, yet only 143 emergency shelter beds are dedicated to this population.6 There are an additional 142 beds of transitional and permanent supportive housing that LGBTQ youth can apply for, but this still comes nowhere near to serving the entire affected population.

Sleeping in public spaces

Doubling-up

General population shelters

Metropolitan areas like New York City attract LGBTQ youth because of their liberal politics and strong presence of LGBTQ communities and networks. On arrival, however, many find that rent is prohibitively high and the process of finding subsidized housing is long and complicated. This problem combined with an inaccessible and often biased job market, lower education rates for this population, and increased physical and mental health needs all contribute to the high rate of LGBTQ youth on the street. While these cities offer youth a sense of acceptance and anonymity, they lack the infrastructural resources to support this population. Many LGBTQ youth experiencing homelessness resort to drug use and sex work to cope with their situation. Transgender homeless youth are especially at risk; they are about three times more likely to engage in survival sex than cisgender homeless youth.7 The HIV rate for trans youth who had experienced homelessness was 7.12%, compared to a rate of 1.97% in trans youth with stable housing.8 Sexual violence is also a particular concern for LGBTQ homeless youth. 58.7% of LGBTQ homeless youth have been sexually victimized; LGBTQ youth are roughly 7.4 times more likely to experience acts of sexual violence than heterosexual homeless youth.9 Homelessness also exacerbates mental health issues that LGBTQ youth often already face; LGBTQ homeless youth commit suicide at an alarmingly high rate — 62%.10 It is notable but not surprising that this issue intersects with other systemic problems in the United States. For example, the vast majority of homeless LGBTQ youth come from low income families and around 90% of the occupants of LGBTQ specific youth shelters in NYC are people of color.11

Drop-in center

Van outreach

Counseling

ENTRY POINT INTO SAFER SPACE

LGBTQ youth often go through a number of different housing situations before arriving at one of the LGBTQ specific shelters that are discussed in this document. There are various ways they find out about these safer and more inclusive shelter spaces. Sometimes they hear about these shelters through word-of-mouth, the internet, or the shelters’ van outreach on the streets; other times they are referred through institutionalized resources such as social workers, the criminal justice system, or healthcare providers. Even after staying in LGBTQ shelters and transitioning into more stable housing arrangements, youth sometimes find themselves back in unstable situations due to some of the underlying problems discussed earlier including mental and physical health issues. Many of the organizations described in this document attempt to address those problems as well in order to have a deeper and longer-lasting impact.

GENERAL POPULATION SHELTERS

Shelters dedicated specifically to LGBTQ youth are extremely important given the needs and vulnerabilities of this particular population. The general population shelter system can often aggravate existing mental health conditions in youth and reinforce feelings of isolation. LGBTQ youth experience high rates of violence, sexual assault, and robbery within these shelters. Homeless trans youth are at an especially high risk of violence, sexual assault, and poor mental and physical health within those spaces. These situations are exacerbated by the gender segregation and warehouse-style layouts of general population shelters. As youth, they have specific needs as well. Legally in the United States, unaccompanied homeless youth are entitled to a “homelike” environment according to the Runaway Homeless Youth Act of 1974. There are federal guidelines in place regulating the number of young people allowed to stay in one room, as well as the conditions of the space, but these guidelines are not always followed.12 This publication examines the existing shelter types and resources that currently serve LGBTQ youth experiencing homelessness in New York City. By examining best practices and potential opportuni- ties, we intend to make suggestions for the future of solving this crisis.

Explainer: Questions and Answers on Homelessness Policy and Research: A National Approach to Meeting the Needs of LGBTQ Homeless Youth, National Alliance to End Homelessness, April 2009.

Emily Nonko, “‘Raise the Age’ Vote Raises Hopes of Homeless Youth,” The Village Voice, March 7, 2018, https://www.villagevoice.com/2018/03/07/raise-the-age-vote-raises-hopes-of-homeless-youth/?fbclid=IwAR33cAGZ Rv5-nRJgkCOAEwFB8HKlVDcFQ1cI0DRR2D7wFVOKSEbl9aZFM.

Mary Cunningham, Michael Pergamit, Nan Astone, Jessica Luna, “Homeless LGBTQ Youth,” Urban Institute, August 2014.

“How Many Homeless Youth Are In America?,” National Network for Youth, accessed April 14, 2019, https://www.nn4youth.org/learn/how-many-homeless/.

“LGBTQ Youth Crisis,” Ali Forney Center, accessed April 14, 2019, https://www.aliforneycenter.org/about-us/lgbtq-youth-crisis/.

“Youth Crisis Stats,” Ali Forney Center, accessed April 14, 2019, https://www.aliforneycenter.org/_aliforney/assets/File/Youth%20Crisis%20Stats.pdf

Nicholas Ray, “An Epidemic of Homelessness: Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Youth,” Washington DC: National Gay and Lesbian Task Force, 2006.

“Gender Minority & Homelessness: Transgender Population,” In Focus, Vol 3, Issue I, 2014: 1-6.

“LGBTQ Homelessness.” Washington DC: National Coalition for the Homeless, 2009.

Ibid.

Carl Siciliano, executive director of the Ali Forney Center, personal interview with Gwendolyn Stegall and Christine Giorgio for this publication, January 25, 2019.

Carl Siciliano; “Runaway and Homeless Youth Act (RHYA) (P.L.110-378): Reauthorization 2013,” The National Network for Youth, accessed April 14, 2019, https://www.nn4youth.org/wp-content/uploads/NN4Y-RHYA-Fact-Sheet-2013.pdf.

1

Existing Safe Space: LGBTQ Shelter Types and Organizations

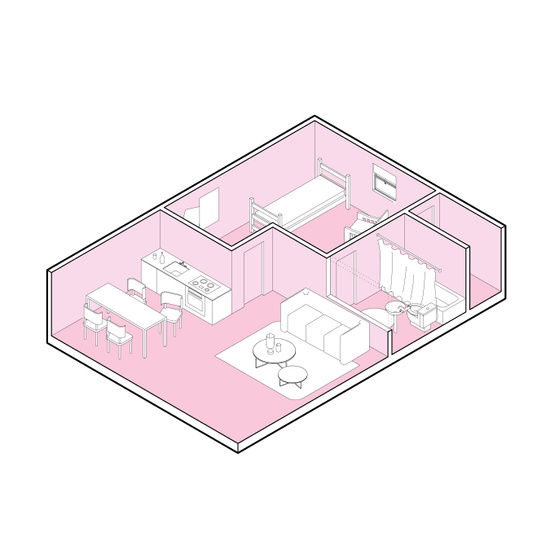

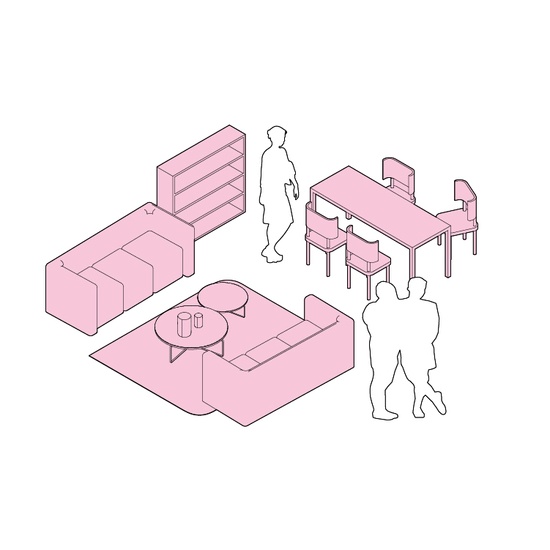

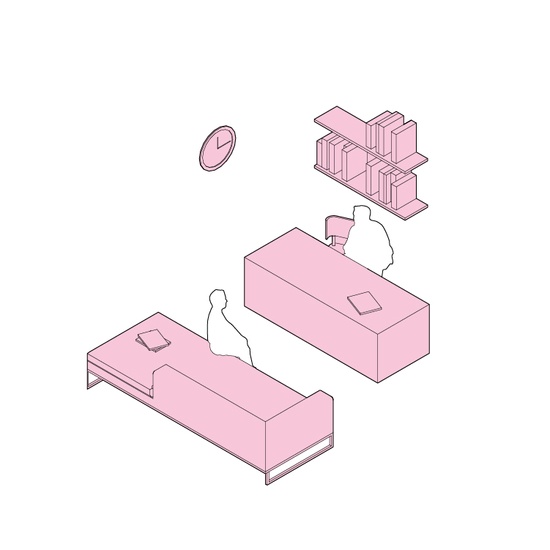

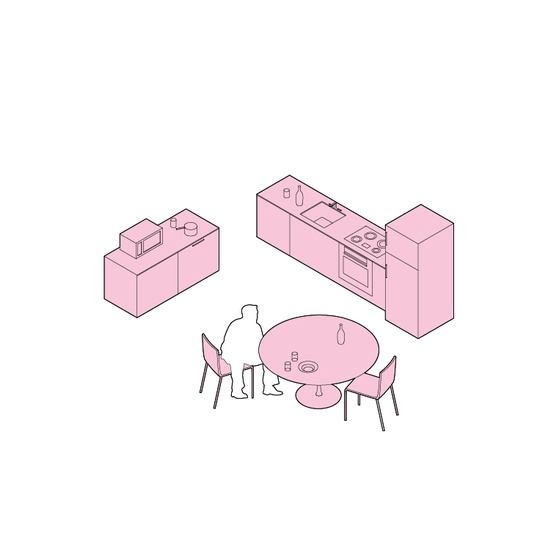

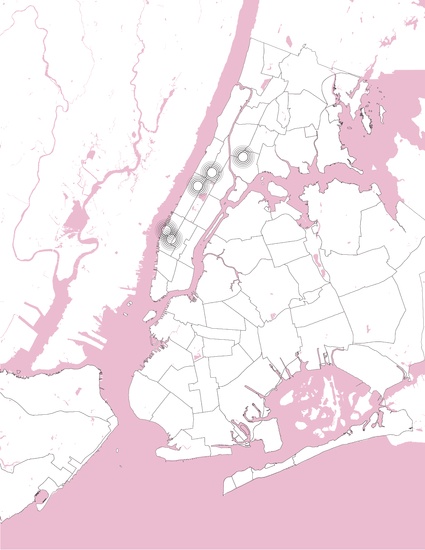

LGBTQ homeless shelters vary widely in their spatial configurations. Our research highlights three shelter typologies categorizing existing organizations operating in New York City: Drop-In Center, Emergency Housing Shelter, and Supportive or Transitional Housing. After describing each typology, a list of examples is provided. Across all of the organizations researched, there are 285 total beds dedicated to housing LGBTQ homeless youth in the city. The diagrammatic representations are not specific to any of the case studies, but offer a general overview of the components of each type. More specific snapshots from these case-study shelters can be seen in the drawings that mark transitions between chapters in this book.

The three types of shelters often serve the same population at different points in their progression out of homelessness by providing critical services and housing. This is often facilitated through references or interactions made at one of the entry points to a safe space. For example, youth often arrive to a drop-in center where they can place an application for transitional housing, or make friends with other youth and hear of an emergency shelter that can house them for the night.

Drop-in center

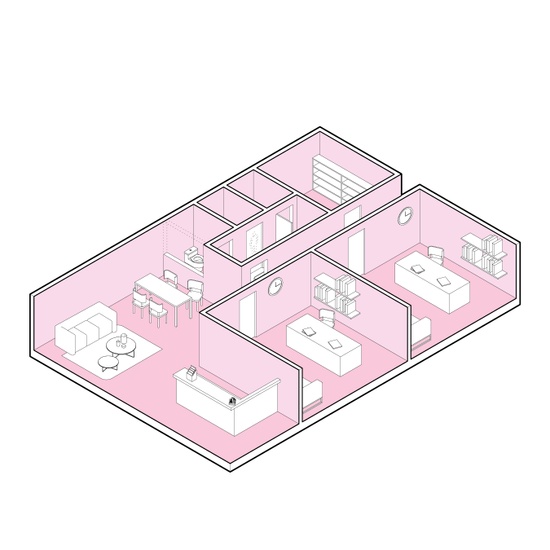

Drop-In Center

Drop-in centers are significant temporary safe spaces for LGBTQ youth

experiencing homelessness. They do not offer overnight sleeping arrangements,

but instead offer access to crucial services and are sometimes open

twenty-four hours. Each center differs in services offered, but all centers

generally provide youth a safe space to relax and socialize, access to counseling,

referrals to offsite STI testing and other healthcare services, as well as

workshops for education and career advancement. In addition, larger centers

typically offer computer access, regular meals, gender neutral bathrooms

with showers, and laundry facilities.

HETRICK MARTIN INSTITUTE (HMI)

The Hetrick Martin Institute provides a wide range of direct services for LGBTQ youth and an extended set of services for those experiencing homelessness. They range from education and workforce training to health services and arts programs, as well

as counseling and housing placement assistance services. HMI has two locations, one in lower Manhattan and one in Newark, NJ, neither open twenty-four hours, but both with daily drop-in hours. The Manhattan location also has a nightly free dinner.

ALI FORNEY CENTER (AFC)

The Ali Forney Center is the largest LGBTQ youth shelter in the United States and offers a wide variety of services and housing. The organization provides all three forms of housing support, and is therefore listed in each section. The AFC manages multiple locations in Manhattan, Brooklyn, and Queens, but their drop-in center is located in Harlem. Weekend and overnight hours are when LGBTQ homeless youth are most vulnerable and when services are not available to them. In response, the

AFC’s drop-in center became the nation’s first twenty-four-hour drop-in program for LGBTQ homeless youth in January of 2015. This location is also their primary intake center, where youth are referred to their emergency housing or transitional housing

sites. Their drop-in center offers onsite medical services, and normally functions as the headquarters for their service offerings, which include career, educational, and health options.

Emergency shelter

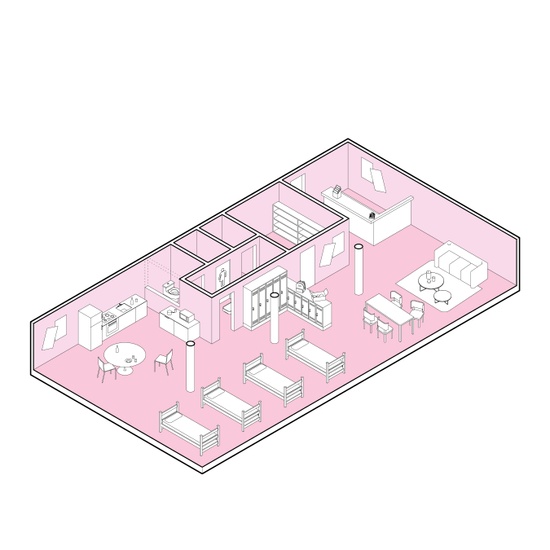

Emergency Shelter

Emergency shelters offer a critical resource to LGBTQ youth, since they are often the first entry point to LGBTQ specific housing. Currently there are 143 emergency beds for LGBTQ youth in New York City. Shelters vary widely in terms of their organization and layout given huge dissimilarities between their funding and organizational models. Some organizations, such as the Ali Forney Center, have spaces dedicated solely to emergency housing, while other organizations use makeshift spaces to provide youth with housing. Emergency shelters are sometimes run by organizations not solely dedicated to housing LGBTQ youth and often provide shelter in vacant spaces. Sylvia’s Place, for example, is run by a church organization and the shelter is located in the unused basement of the church. The bed configuration changes daily since the bedding is put up every night and taken down every morning. Although emergency housing does not offer long-term solutions for youth, these spaces serve a crucial need by offering beds and shelter on a short-term basis.

MARSHA’S HOUSE Marsha’s House is an emergency housing facility in the West Bronx operated by Project Renewal. This facility has eighty-one beds for youth and young adults between the ages of eighteen and thirty. This shelter is unique in that it is the first and only program that allows space for LGBTQ identifying persons over the age of twenty-four. Notable resources at Marsha’s House include a culinary arts training program as well as other educational and vocational opportunities.

SYLVIA’S PLACE

Sylvia’s Place is a charity associated with the Metropolitan Community Church of New York (MCCNY), located in the basement of the church in Hell’s Kitchen. Sylvia’s Place provides meals, medical support, and legal aid to homeless LGBTQ youth. It offers a drop-in service six days a week, as well as emergency overnight housing. Assistance is prioritized for vulnerable populations such as those experiencing trauma, living with HIV/AIDS, and transgender or intersex youth. There are at least ten beds available at Sylvia’s Place and the maximum stay allowed is ninety days. Because of its makeshift quality, the organization has come under criticism for being unsanitary and unsafe.

THE ALI FORNEY CENTER (AFC)

The Ali Forney Center’s emergency housing program operates out of four sites, located in Brooklyn and Queens, and houses fifty-two homeless youths every night. Depending on the site, resident stays range from one to six months in home-like apartments with nightly home-cooked meals. Although it is the largest LGBTQ youth shelter in the United States, AFC still frequently has an emergency housing wait list in excess of 200 youth. This can cause wait times as long as six months

to access the emergency housing facilities. The ultimate goal of the organization’s emergency housing is to stabilize young people and move them into the more independent transitional living program.

Transitional housing

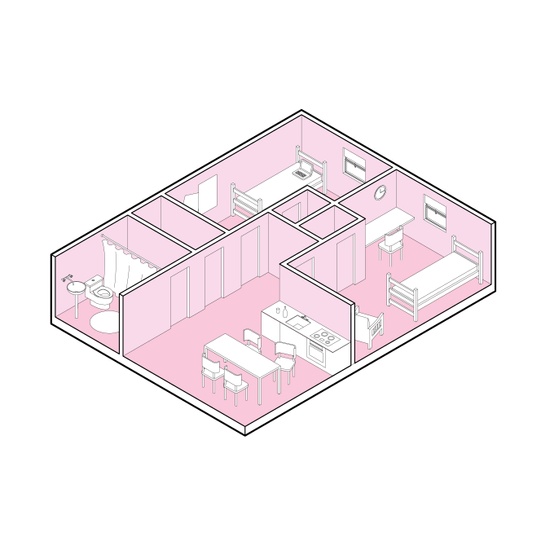

Transitional Housing

Transitional Housing is long-term supportive housing offered to LGBTQ homeless youth in the hopes of eventually placing them in permanent stable housing. Currently there are eighty-two transitional beds for LGBTQ youth in New York City. Although still subject to a time limit, youth are eligible to stay for an extended period of time in this home-like housing while gaining the support and skills to move on to a permanent residence. Notable resources for these shelters include on-site intake offices and social worker visits. The house-like model of transitional housing is the most ideal for LGBTQ youth experiencing homelessness in order to successfully transition youth towards independent living.

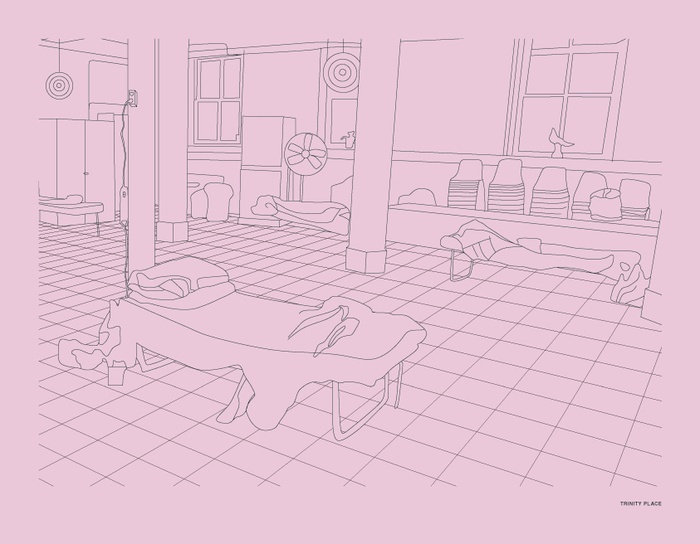

TRINITY PLACE

Trinity Place is a transitional housing shelter based out of the basement of Trinity Lutheran Church on the Upper West Side of Manhattan. Youth must be referred to Trinity Place by an assigned social worker, case manager, or a representative within their referring social service organization. Accompanying applications must include health assessments and test results. A formal wait list is not maintained due to the shelter’s limited number of beds, but the organization continuously accepts applications and encourages routine inquiry regarding bed availability. Its small size creates a family-like setting where meals are often eaten communally with other occupants. Like Sylvia’s Place, Trinity Place is an example of adapting underutilized spaces for temporarily housing homeless youth. Ten cots are set-up and removed daily to make the space usable for church programming. Trinity Place provides individual and group counseling, access to education and career resources, and other supportive services for up to eighteen months of stay.

THE ALI FORNEY CENTER (AFC)

AFC currently runs transitional housing facilities with seventy-two beds in shared apartments across Manhattan and Brooklyn. LGBTQ youth can reside in the AFC’s transitional housing program for up to two years while they maintain employment, continue their education, and prepare for independent living. The Center’s Transitional Housing Program prepares residents for independence by providing access to in-house case management and financial planning services, higher education enrollment, and an independent living coach to guide residents

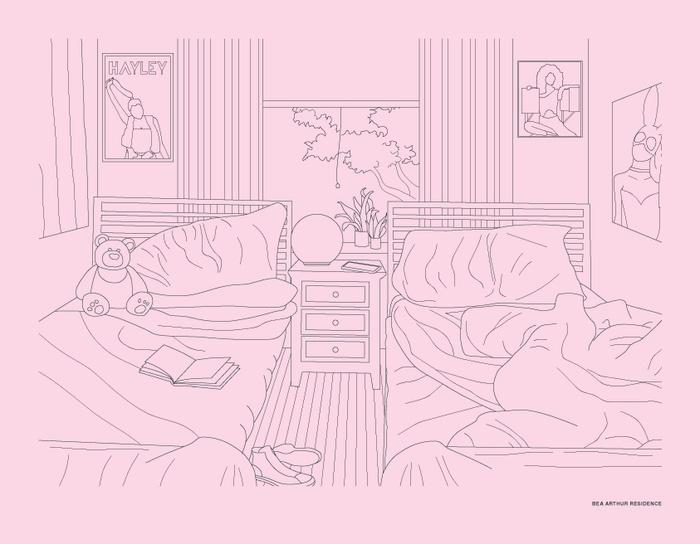

through the transitional housing phase and beyond. Located in the Lower East Side, the Bea Arthur Residence represents a new organizational model for a shelter. AFC owns and operates the building, a transformational development to be discussed more in-depth in the next section. Opened in 2018, the three-unit

building of three bedroom apartments houses up to eighteen homeless LGBTQ youth at any given time. In tandem with neighborhood developer the Cooper Square Committee, architectural firm Magnusson Architecture and Planning was tasked with renovating the derelict four-story historic structure into a space

dedicated solely to housing LGBTQ youth. The Ali Forney Center is building another transitional housing residence of twenty-one studio apartments that they will own in Astoria, next to the St. Andrew’s Church, where they currently operate an emergency shelter.

Permanent supportive housing

Permanent Supportive Housing

Permanent supportive housing is a model of affordable housing that is meant to support individuals and their families who have unstable housing or are experiencing homelessness and to help them to lead more stable and independent lives. Sixty units of permanent supportive housing are currently allocated for LGBTQ youth in New York City. This housing typology includes increased access to stable and continuous services for formerly homeless youth. The approach of facilitating permanent housing for LGBTQ youth experiencing homelessness does present structural challenges and opportunities. These facilities are not able to serve as many individuals as shelters with time-limits, but they offer an effective long-term solution.

TRUE COLORS RESIDENCE - HARLEM & BRONX (TCR) The True Colors Residences are run by the West End Residences, though partially financed by Project Renewal. They have two locations: one in Harlem which opened in 2011 with thirty beds, and one in the Bronx, which opened in 2015 with an additional thirty beds. TCR distinguishes itself as a non-time-limited shelter for homeless LGBTQ youth aged eighteen to twenty-four. Residents pay an income adjusted rent payment while they live at TCR. Each studio has a private bathroom and kitchen, and the facility provides communal spaces for residents, as well as services including life skill coaching, counseling, and job readiness trainings. A range of additional services such as GED classes and healthcare are available through partnerships with other agencies.

2

Funding Safe Space: Real Estate and Planning Analysis

The intent of this section is to highlight some of the most common funding resources available and to identify the local, state, and federal organizations that provide these funds for Drop-In Centers, Emergency Shelters, Transitional Housing, and Permanent Supportive Housing. Case studies are provided for each category to show strategies that organizations have successfully implemented. The case studies include: Drop-In Center - Hetrick Martin Institute New Jersey, Emergency Shelter - Marsha’s House, Transitional Housing - Bea Arthur Residence, and Permanent Supportive Housing - True Colors Residence Bronx. In addition, we discuss some of the requirements that are tied to certain funding sources and other incentives that are available to providers. We hope that this will provide useful information on resources available to those seeking to alleviate the serious lack of facilities geared towards LGBTQ youth homelessness.

Drop-In Center

HETRICK MARTIN INSTITUTE NEW JERSEY

Hetrick Martin Institute New Jersey is a nonprofit 501©3 that provides services to LGBTQ youth. While originally founded in New York, the New Jersey branch recently began operating independently. Most of HMI New Jersey’s funding comes through a combination of county and federal grants, individual and corporate donations, as well as contracts with the Newark school system for counseling/programming services provided to youth. Their federal grants come through the Victims of Crimes Act (VOCA). Since LGBTQ youth are at high risk of crime incidence, HMI qualifies for the funding.

Emergency Shelter

MARSHA’S HOUSE

Marsha’s House is run by Project Renewal, which

was awarded a contract with the City’s Department of Homeless Services (DHS). The facility is leased by Marsha’s House, while rent and social services are paid through the DHS contract. To apply to the DHS, Project Renewal had to demonstrate site control, which means demonstrating the possession of a title to the land, a lease, or a contract to purchase or lease a property. They met this requirement by entering into a lease contract before they were able to submit for DHS funding. DHS funding also carries specific requirements for operations staff and case managers, and design mandates, such

as single adult shelters must separate male or female residents. While New York state regulations mandate that shelter operations separate genders by floor, Marsha’s House was able to obtain approval to create room groupings by self-determined gender identity.

Transitional Housing

BEA ARTHUR RESIDENCE

Ali Forney partnered with Cooper Square Committee to develop the Bea Arthur Residence in coordination with the New York City Housing Development Corporation (HDC). They adaptively reused a four-story townhouse to turn it into transitional housing with eighteen beds and an Ali Forney services center on the ground level. Bea Arthur is a suite-style residence where tenants rent a room

rather than an apartment. HDC typically does not fund suite-style residential and transitional housing, but the developers were able to work with the city to bring this transitional housing program to fruition. Each resident commits to a twenty-four-month program with Ali Forney, by the end of which they transition into permanent housing. The development was financed with construction to permanent funding from the New York City Council, borough president, and an unsecured loan. Additionally, they received gap funding during construction from the Dormitory Authority of the State of New York. The largest percentage of the Ali Forney Center’s operating budget goes to rent, so owning property frees up funds for other important needs.

Permanent Supportive Housing

TRUE COLORS RESIDENCE

True Colors Residence Bronx is permanent supportive housing developed by West End Residences that focuses on serving LGBTQ youth. This is the second True Colors Residence completed by West End. The first was built in Harlem and opened in 2011. In the supportive housing model, potential tenants are referred by the DHS or Department of Youth and Community Development (DYCD) and enter into a lease for an apartment unit. Tenants are responsible for paying a certain percentage of their income for rent, while the rest of the rent payment is covered by subsidies such as Section 8 vouchers. The development was financed through a combination of 9% tax credit equity, HPD Supportive Housing Loan Program (SHLP), conventional construction loans, and funds from city council and the Bronx borough president. The 9% tax credit is allocated on a competitive basis according to an annual funding round administered by HPD. There is also a 4% tax credit that is automatically allocated if the applicant can demonstrate sufficient gap financing to make the deal feasible. The 4% tax credit is accompanied by tax exempt bonds issued by HDC or the New York State Housing Finance Agency. Generally, deals with one hundred units or less would be able to take advantage of 9% tax credits and conventional debt, while deals with greater than one hundred units would opt for 4% tax credits and tax exempt bonds.

Recommendations

In cases where it is desirable or necessary to build shelters from the ground up, there have been examples of providers securing a twenty-year contract with DHS in order to obtain construction financing. This entails matching a construction loan term to the twenty-year DHS contract. The mortgage is then insured by the State of New York Mortgage Agency and sold to an investor such as a pension fund. There has been some shift towards a new model of co-locating emergency shelters with permanent supportive housing called the HomeStretch program. This model can be beneficial by creating a continuity of services. For example, counselors and case workers can stay with occupants as they move from the shelter program to the permanent housing component. HomeStretch has been implemented already for general population shelters, but it has yet to be implemented for LGBTQ youth. While HomeStretch involves the simultaneous development of an emergency shelter and supportive housing, Ali Forney is seeking to use a similar strategy by developing transitional housing next to one of their existing shelters in Queens.

In the case studies above, some organizations lease their spaces, such as Marsha’s House, while others own the property outright, such as the Bea Arthur Residence. A benefit of ownership is the real estate tax exemptions available for Low Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) developments and nonprofits. LIHTC developments qualify for full real estate tax exemptions under 420-c. Projects that do not use tax credits but are owned by a nonprofit may still qualify for a full real estate tax exemption under 420-a.

New York City HPD provides gap financing to supportive housing developments through the Supportive Housing Loan Program (SHLP). To qualify for SHLP funding, the development must set aside 100% of units for tenants earning up to 60% of the area median income. A minimum of 60% of units must be reserved for homeless and disabled tenants referred by city or state agencies. Operating subsidies are very important for supportive housing, since tenants are referred from homeless shelters and cannot afford rent payments. In the past, deals relied on Section 8 vouchers. However, there are city and state initiatives available, such as NYC 15/15 and Empire State Supportive Housing Initiative. Both are allocated based on competitive RFPs. The NYC 15/15 is administered on a rolling basis, while the Empire State program funding is once a year. Applicants who want to serve LGBTQ youth must affirmatively state their intention in the application and demonstrate expertise in serving that population.

3

Making Safe Space: Ideal Conditions for LGBTQ Youth

Although there are government standards for the way some shelter spaces should be configured, these regulations are not always followed. The regulations that do exist, such as the Runaway Homeless Youth Act which is a guideline that encourages youth shelters to be “homelike,” do not go far enough to serve the LGBTQ youth population. Given the difficult issues that LGBTQ youth are facing, an adequate space that contributes to their sense of inclusion is crucial to establishing a path towards housing stability. Based on our research, we have compiled a list of best practices that fulfill basic needs and contribute to a sense of belonging and community in supportive housing organizations. Individually, some of these recommendations may seem mundane, but looking at them through a queer lens reveals deeper sensitivities to the LGBTQ youth population. All together, these components strive to fulfill a deeper need for acceptance and community, making the shelter not just a resource but a haven. Some of these amenities can be implemented with little or no cost (such as inclusive signage and staffing decisions while others require planning and decision making at early stages of development (such as room layouts). We emphasize that this list is idealized since not all shelters have the resources or funding to provide all of these amenities to their occupants.

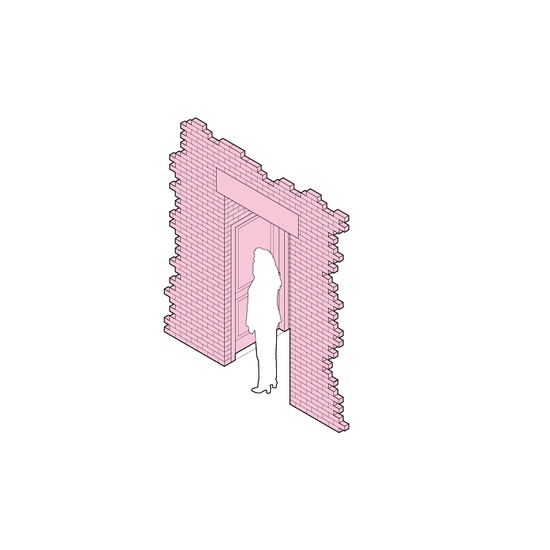

Discreet Entry

Discreet Entry

Not all youth are comfortable sharing their LGBTQ identity or that they are experiencing housing instability. A discreet entrance diminishes the possibility of “outing” a visitor or occupant to friends or family and de-stigmatizes the shelter itself. It also provides a level of safety from people who may potentially wish harm on this population. A discreet entry is particularly important for more permanent type residences, since these strive to look and feel as “home-like” as possible.

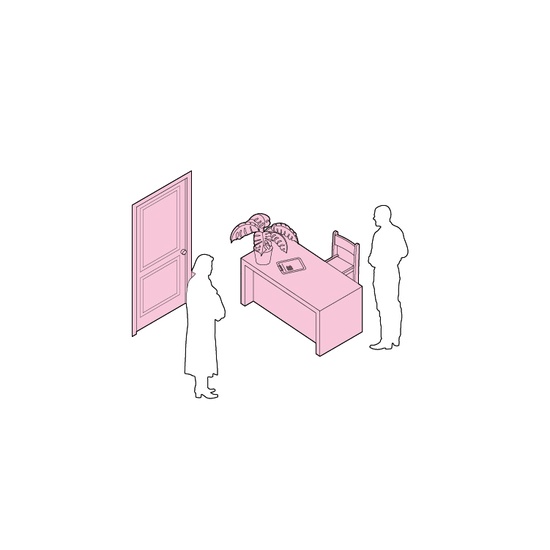

Door check-in

Door Check-In

LGBTQ youth can be the targets of violence or aggression. A door check-in

ensures the safety of those inside and establishes it as a safe space for the

occupants. A person stationed at the door can help enforce curfews, make

sure youth do not bring contraband into the shelter, and track who enters and

leaves the space. They also provide a sense of familiarity and recognition

so young people feel seen and taken care of.

Communal Space

Communal Space Whenever possible, organizations should attempt to have communal spaces that allow youth to build relationships and gain a sense of community. These spaces can play out differently depending on the shelter typology. A lounge or meeting room may serve as communal space in services organizations, while a living room or communal kitchen may be the gathering places in more home-like environments.

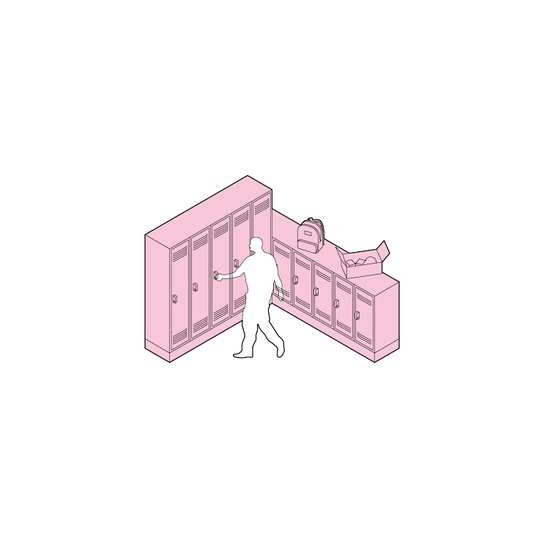

Lockers

Lockers

Safety, a sense of personal space, and a place to put one’s valuables are crucial. If a personal locked room is not available for a young person, a locker can be a valuable first piece of ownership.

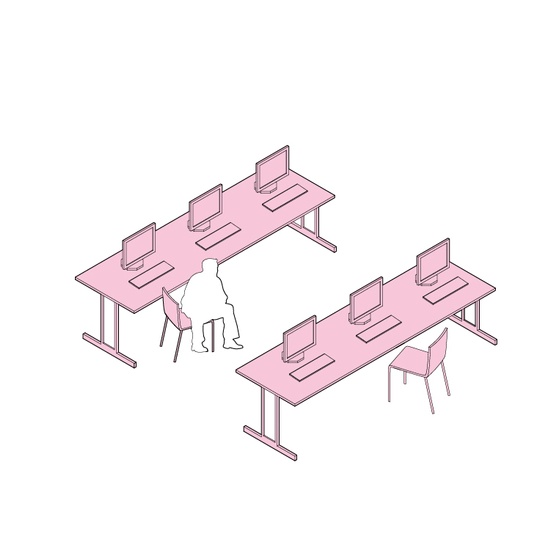

Computer Access

Computer Access Without a computer (something many youth cannot afford), mundane tasks such as applying for affordable housing, signing up for healthcare, finding jobs, or doing homework become much more difficult. Further, access to social media, news, and other outlets help to normalize the life of a young person experiencing homelessness.

Private Bedroom

Private Bedroom

While youth should be kept under surveillance for self-harm or safety issues, they should also be given a sense of personal space. One of the biggest issues affecting queer youth staying in the general population shelter system is a lack of privacy which can exacerbate existing mental health issues. While having a roommate may be appropriate for some young people, others would thrive better having their own space.

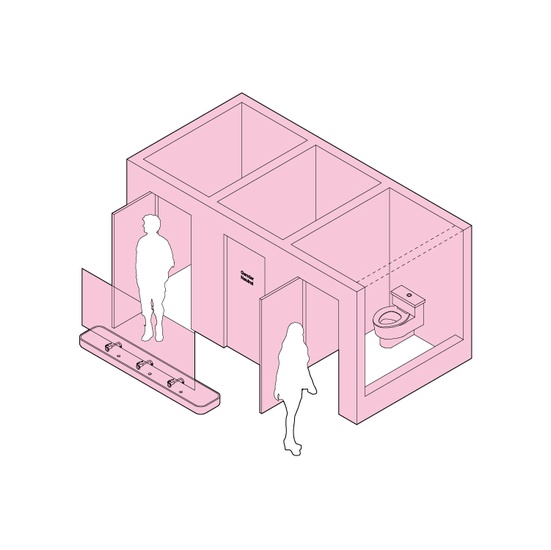

Gender Neutral Bathrooms

Gender Neutral Bathrooms

Single user, fully enclosed toilets with communal sinks is an ideal bathroom configuration. This maintains maximum privacy while allowing for a large number of facilities. Gender neutral bathrooms are especially important for trans youth as well as breaking down the gender binary which is part of a larger LGBTQ perspective.

Counseling with Private Space

Counseling with Private Space

It is crucial that organizations are sensitive to issues of privacy and that they make sure that LGBTQ youth feel comfortable sharing intimate issues. Spaces for counseling should be soundproof and private.

Access to Healthcare

Access to Healthcare

For many young people access to healthcare is crucial to successfully transitioning out of homelessness. Adjacency to local clinics or partnerships with mobile clinics is highly recommended for any type of LGBTQ youth shelter. LGBTQ youth require everything from regular doctor visits, to mental healthcare, to STI testing and treatment.

Kitchen

Kitchen

Communal or shared kitchens allow occupants to both cook for themselves and also create a sense of community with other youth. This is also an opportunity for residents to be taught life skills such as cooking, meal planning and making nutritional choices that fit their diet.

Laundry

Laundry

When possible, laundry rooms should be well-stocked and discreet. LGBTQ youth often face insecurities that can be aggravated by having their laundry publicly visible or not being able to wash their clothes for days at a time.

Diverse Queer Staffing

Diverse Queer Staffing

Staffing is a crucial part of establishing a safe, non-judgmental space for queer youth. Whenever possible, many spectrums of LGBTQ identity should be represented since youth often feel more comfortable with staff who share similar experiences or backgrounds. If diverse LGBTQ staff is not possible, extensive training to better understand and work with this particular population is especially important.

Affirmative Signage

Affirmative Signage

Signage and artwork can go a long way towards making youth feel comfortable and accepted. Signage can vary from artwork created by youth themselves, posters reflecting the interests of the occupants, or affirmative messages promoting a sense of LGBTQ pride and inclusion such as rainbow and identity based flags.

4

Conclusion

This publication presents an investigation of the current state of shelters for LGBTQ youth experiencing homelessness in New York City. We hope that by examining how existing spaces operate and how they are organized architecturally, we can put forth examples of best practices for organizations currently operating or in the process of opening LGBTQ youth shelters. We hope to contribute to solving this issue by providing our insight as architects, urban planners, and real estate planners, highlighting aspects often overlooked by the social services and health sectors. Our suggested ideal components of an LGBTQ youth shelter are intended to help future projects in creating affirming, effective, and safe spaces for this vulnerable population.

The research included in this document is far from exhaustive. We have included our investigations into the funding and real estate models for existing organizations. However, there are numerous ways that an organization can structure its finances. We present existing models for future projects to follow, and potential learning for future institutions. Ideally our preliminary research can be a seed for future projects and investigations into this topic. An important next step in further exploring this topic would be a conversation with more stakeholders, most importantly including the insight of LGBTQ youth themselves. The scope of our project did not allow for interviews with LGBTQ youth currently experiencing homelessness or those formerly in that situation; those voices would be crucial in a further investigation of this topic and understanding the individual needs of youth in a specific space. We hope to pass this work forward to another set of professionals who can produce fruitful future projects.

5

Appendices

LGBTQ Youth Shelters in NYC

ALI FORNEY CENTER

Headquarters

224 W 35th St

New York NY 10001

(212) 629-7440

Drop-In/Intake Center

321 W 125th St

New York, NY 10027

(212) 206-0574

aliforneycenter.org

Founded 2002

Carl Siciliano

52 emergency beds

72 transitional housing beds (soon

to be 93)

Shelter Types

Drop in Center

Emergency Housing

Transitional Housing

Services Housing

GED courses / education support

Counseling services

Food

STD testing

Career counseling

Housing placement assistance

MARSHA’S HOUSE

480 E 185th St

Bronx, NY 10458

(929) 445-5335

projectrenewal.org

Founded 2017

Project Renewal

81 Beds

Shelter Types

Drop in Center

Emergency Housing

Transitional Housing

Services

Housing

GED courses / education support

Counseling services

Food

STD testing

Career counseling

Housing placement assistance

SYLVIA’S PLACE

446 W 36th St

New York NY 10018

(212) 629-7440

mccny.org/mccnycharities

Founded 2003

Metropolitan Community Church

10 Beds

Shelter Types

Drop in Center

Emergency Housing

Services

Housing

Counseling services

Food

Career counseling

Housing placement assistance

TRINITY PLACE

164 W 100th St

New York, NY 10025

trinityplaceshelter.org

Founded 2006

Kevin Lotz, Heidi Neumark, & Lydie

Raschka

10 Beds

Shelter Types

Emergency Housing

Transitional Housing

Services

Housing

GED courses / education support

Counseling services

Food

STD testing

Career counseling

Housing placement assistance

TRUE COLORS RESIDENCES

Exact addresses undisclosed

Founded 2011 (Harlem)

2015 (Bronx)

West End Residences (with assistance from Project Renewal)

westendres.org/residences/true-col- ors-residence/ (Harlem)

westendres.org/residences/true-colors- bronx (Bronx)

60 Beds (30 per building)

Shelter Types

Permanent Supportive Housing

Services

Career counseling

Counseling services

GED courses/education support

STI testing/physical health care

Map of Existing Sites

Organizations Serving LGBTQ Homeless Youth in NYC

THE AUDRE LORDE PROJECT

146 West 24th Street, 3rd Floor

New York, NY 10011

(212) 463-0342

85 South Oxford Street

Brooklyn, NY 11217

(212) 463-0342

alp.org

The Audre Lorde Project (ALP) is an organization dedicated to supporting LGBTQ People of Color in New York City. Although it does not provide specific housing-related services, ALP’s community organizing working groups tackle issues that many LGBTQ youth experiencing homelessness face, such as the

criminal justice system, trans rights, healthcare, employment, education, and immigration concerns.

BREAKING GROUND

505 8th Ave

New York, NY 10018

(212) 389-9300

info@breakingground.org

breakingground.org

While not LGBTQ or youth specific, Breaking Ground is an organization that owns and manages apartment buildings available to homeless and vulnerable populations through transitional and permanent housing programs. Young adults without family support and people living with HIV/AIDS are among the groups that Breaking Ground targets. They also

offer mental and physical healthcare and mentoring services.

THE DOOR

Door-A Center of Alternatives

555 Broome St

New York, NY 10013

(212) 941-9090

info@door.org

door.org

The Door is an organization serving the needs of youth at risk in New York City. The Door offers a wide range of services including education and workforce training, mental health counseling and health

services, legal counseling, free meals, and arts programming. They have specific drop-in hours for runaway

and homeless youth and they offer LGBTQ specific counseling and leadership programs.

HETRICK MARTIN INSTITUTE

2 Astor Place

New York, NY 10003

(212) 674-2400

550 Broad St, Suite 610

Newark, NJ 07102

(973) 722-5488

hmi.org

Hetrick Martin Institute provides a wide range of direct services for LGBTQ youth, and an extended set of services for those experiencing homelessness. These services range from education and workforce training, to health and counseling services, to arts programming, to housing placement services.

THE LESBIAN, GAY, BISEXUAL & TRANSGENDER COMMUNITY CENTER

208 West 13th Street

New York, NY, 10011

(212) 620-7310

gaycenter.org

The LGBT Community Center is a space dedicated to supporting LGBTQ people to building healthy and successful lives. It offers youth-specific services, such as

education, healthcare, mentoring, and arts and culture programs. Although the services have more narrow hours of operation, the Center’s building provides a space from 9:00 a.m. to 10:00 p.m. most days that is staffed, welcoming, and safe, and where LGBTQ young people can find out about other organizations

and services.

NEW ALTERNATIVES

410 West 40th Street

New York, NY 10018

(718) 300-0133

info@newalternativesnyc.org

newalternativesnyc.org

New Alternatives provides a wide range of programs aimed at helping LGBTQ youth experiencing homeless reach stability. They provide case management, basic needs services, life skills training, and HIV testing among others.

THE TREVOR PROJECT

PO Box 69232

West Hollywood, CA 90069

info@thetrevorproject.org

thetrevorproject.org

The Trevor Project provides emergency

crisis counseling for LGBTQ youth, providing crisis intervention and suicide prevention. Their 24/7 call line allows troubled youth to reach out to trained volunteers. Given the dire state of mental health that many LGBTQ young people are in when they experience homelessness, this is an important resource for them. Although their headquarters are in California, their services are nationwide and are an important resource for youth in New York City.

TRUE COLORS UNITED

311 W 43rd St 12th fl.

New York, NY 10036

(212) 461-4401

truecolorsunited.org

Founded by Cyndi Lauper, True Colors United is an organization committed to tackling the LGBTQ youth homelessness crisis nationwide. True Colors United offers free institutional training and resources on how to respond to the needs of LGBTQ youth experiencing homelessness, and advocates at different scales of government and media for

funding and services for youth.

Many organizations in New York City are dedicated to supporting homeless youth, some with a special focus on LGBTQ youth. They provide services ranging from attending to the population’s immediate needs, such as physical and mental healthcare, to long-term case management and youth leadership, helping individuals attain stability and independence. These organizations constitute a network of places and programs that respond to the issue of LGBTQ youth homelessness, building supportive communities around this population and supplementing the work of the shelters. This list is not meant to be a comprehensive documentation of every possible organization that may offer services to this population (there are many healthcare specific organizations, for example, that are not listed here), but rather it is meant to give examples of organizations that support this population in various ways.

LGBTQ Youth Shelters Nationwide

Arizona

ONE•N•TEN

3660 N 3rd St

Phoenix, AZ 85012

onenten.org

California

LOS ANGELES LGBTQ CENTER

Youth Center on Highland

1125 N McCadden Pl

Los Angeles, CA 90038

lalgbtcenter.org

SAN DIEGO LGBTQ

COMMUNITY CENTER

1807 Robinson Ave, Suite 106

San Diego, CA 92103

thecentersd.org

District of Columbia

WANDA ALSTON FOUNDATION

300 New Jersey Ave NW, Suite 900

Washington, DC 20001

wandaalstonfoundation.org

Florida

PROJECT SAFE

By Pridelines

Miami

pridelines.org

Georgia

LOST-N-FOUND YOUTH HOUSING,

SUPPORTIVE SERVICES

2575 Chantilly Dr NE

Atlanta, GA 30324

lnfy.org

Illinois

360 YOUTH SERVICES

1305 W Oswego Rd

Naperville, IL 60540

PROJECT FIERCE CHICAGO

(not yet operational)

Chicago, IL

www.facebook.com/ProjectFierceChicago

Maine

NEW BEGINNINGS

491 Main St

Lewiston, ME 04240

newbeginmaine.org

Massachusetts

WALTHAM HOUSE

10 Guest St

Boston MA 02135

thehome.org

Michigan

HQ (Drop-In Center)

320 State Street S.E.

Grand Rapids, MI 49503

hqgr.org

OZONE HOUSE

1705 Washtenaw Ave

Ann Arbor, MI 48104

ozonehouse.org

RUTH ELLIS CENTER

Ruth’s House

77 Victor St

Highland Park, MI 48203

ruthelliscenter.org

Minnesota

GLBT HOST HOME PROGRAM

Avenues for Homeless Youth

1708 Oak Park Ave N

Minneapolis, MN 55411

avenuesforyouth.org

New Jersey

Q SPOT

66 Main St

Asbury Park, NJ 07712

qspot.org

THE ESSEX LGBTQ REACHING

ADOLESCENTS IN NEED (RAIN)

FOUNDATION

168 Park Street

East Orange, NJ 07017

essexlgbthousing.org

New Mexico

CASA Q

PO Box 36168

Albuquerque, NM 87176

casaq.org

North Carolina

TIME OUT YOUTH

Host Home Program

1900 The Plaza

Charlotte, NC 28205

timeoutyouth.org

Oregon

UNITY HOUSE

New Avenues For Youth/SMYRC

1220 SW Columbia St

Portland, OR 97201

newavenues.org

Tennessee

METAMORPHOSIS PROJECT OUT

892 Cooper St

Memphis, TN 38104

outmemphis.org

Texas

THRIVE YOUTH CENTER

1 Haven for Hope Way

San Antonio, TX 78207

thriveyouthcenter.com

TONY’S PLACE

1621 McGowen St

Houston, TX 77004

tonysplace.org

This is a list of shelters nationwide that specifically serve LGBTQ youth or are specifically LGBTQ inclusive. Organizations that shelter youth but are not explicitly LGBTQ welcoming were not included, since their inclusiveness could not be verified (LGBTQ youth may not actually feel welcome there). Organizations that serve LGBTQ youth, but do not specifically offer shelter or help in finding shelter were also not included, though it is likely that those organizations fill important needs, especially in places that do not have LGBTQ youth-specific shelters. The list comes from internet searches and from a list generously provided to us by True Colors United. Although there may be organizations that we missed, the shortness of the list is significant — no city has more than one organization (showing New York City to be unique) and no state has more than two organizations. Only fifteen states and the District of Columbia have organizations devoted to sheltering this population at all. Almost all of the shelters are in the biggest cities in the state. Some shelters were purposely built for these organizations, but many are in repurposed buildings and some organizations do not have permanent buildings, but partner with locals to temporarily house young people. Most of the shelters are fairly small and come nowhere near to serving all of the LGBTQ youth experiencing homelessness in the country.

Many other organization have put together similar lists of resources for LGBTQ youth experiencing homelessness. For example, Lambda Legal compiled a more expansive list of organizations by state that serve all LGBTQ youth, which can be found here: www.lambdalegal.org/publications/fs_resources-for-lgbtq-youth