Preface

There are many myths and as many received ideas about Beirut: the city as phoenix, rising from the ashes throughout centuries; the city as bustling and cosmopolitan heart that has historically bridged east and west; a city of endless resilience and resourcefulness of its people, who no tragedy can stop from living life to the fullest, always with the finest willful humor in the face of insurmountable and continuous hardship.

And yet, on August 4, 2020, tragedy pummeled the Lebanese capital, sinking it further into a bottomless pit already layered with entangled and multiplying crises: a continued influx of refugees, political corruption, and stalemate; crippling unemployment and deepening social inequities; financial and economic collapse; and the COVID global pandemic. In the heart of the Port of Beirut, at 6pm local time, one of the largest non-nuclear explosions ever recorded, registering as a 3.5 magnitude earthquake, sent shockwaves across the city, turning the immediate dockside area into a crater approximately 460 feet wide, blowing out windows at Beirut International Airport’s passenger terminal over 5 miles away, and leaving at least 220 dead, 6,500 injured, and 300,000 displaced from their homes.

Even for a city and a people that had seen it all, it is difficult to articulate the extent of this seemingly final blow to those who live in Beirut, as well as to those recently or generations ago exiled who have nevertheless continued to love and be inspired by this city and its capacity to capture the most potent architectural and urban imagination. And so, this design studio at GSAPP, which had been in the works prior to the explosion, has emerged now as a powerful means to channel unspoken and at times unspeakable emotions into an architectural and urban framework through which to open up possibilities for, despite everything, the city’s healing.

The inspiring outcomes of the studio are many, but the two that I believe are most worth noting are a result of the studio’s constraints. First, with the inability to travel to Beirut, the studio had to very quickly build an incredible array of collaborators in Beirut and around the world to understand the complexity of not only the city’s current condition but also its multi-layered histories and, especially, of the seemingly infinite and almost all failed attempts to form it, whether through state-led urban planning, private development, or ‘informal’ interventions. Considering Beirut as an open book, where traces of urban experiments and the socio-economic and political systems that supported them are all present together, constituted a thick context to work from and within.

Second, the sense of deep urgency to adopt the most careful and caring realism led to conceiving the studio as the design of systems of connections: from designing and planning the reconnection of the Port to the city, to reconnecting neighborhoods within Beirut and reconnecting Beirut to the world, to the design of networks of people and collectives—including for instance, the GSAPP Collective for Beirut, which formed alongside the design studio when a group of current students and alumni united to create a powerful and inspiring opportunity to share ideas and come together—all support hope and imagine together new possibilities for engagement and action.

As a microcosm that densely packs and often intensifies to a tragic extent so many of the forces that are at play in the built environment across the world, Beirut for many of us remains a powerful site of learning as well as a unique prism through which to read other places, cities, contexts, and cultures. The work of this studio not only represents the testing of ideas for Beirut’s recovery but is also an open invitation to continue to engage and learn from the city, to support and imagine the possibility of its future, and to strive to imagine and build more equitable and creative forms of urbanity for the future.

Forward

Connecting

It was approximately 11:00am in New York on August 4 when we finished a call with Filiep Decorte, Tarek Osseiran, and Elie Mansour of UN-Habitat regarding a GSAPP architecture studio focused on Beirut for the Fall 2020 semester. They had a long engagement in resourcing new planning initiatives for the city. The studio initiative had originated with the Urban Design Lab in the Earth Institute, and was to focus on improvements in the organization of the Sabra Market and its connection to the city. Also connected to the studio proposal was the World Health Organization that was addressing COVID-19 pandemic strategies for Beirut with the Sabra Market serving as an important test bed.

Within minutes of completing the call the first blast occurred. Everything changed for the subsequent discussions. There was even the question of a Beirut studio at all given the circumstances, but a consensus emerged that a studio could be even more useful than before, with a heightened immediacy. The studio brief changed, but one thread of the initial draft remained which was the challenge of rethinking the very tenets of how planning can be accomplished and how concepts can be reinvented, now with the immediacy of reconstruction as a tangible focus. And after some deliberation from UN-Habitat, the site was shifted from the Sabra Market to Gemmayze because of its proximity to the blast and the loss of a vibrant neighborhood entailing many building and community fabric preservation issues.

In elaborating the brief, further connections to Gemmayze evolved, most importantly through two Gemmayze residents, Candice Naim and Nour Fares who are both graduates of the GSAPP Urban Design Program. Both had suffered the loss of their homes, and input from both was essential in surveying the site conditions before and after; and in providing other essential site information for our study team that could not visit due to pandemic restrictions. This inability to visit the site made it apparent that the studio had to organize itself as a laboratory that could bring various resources together in addressing some of the issues emerging form the blast aftermath. Connections to the city and site became further enhanced with Professor Serge Yazigi at AUB, whose advice was invaluable though out the studio. And at GSAPP, Dean Amale Andraos provided total commitment to ours and other initiatives, including the formation of the GSAPP Beirut Collective that has been instrumental in completing our effort.

As things evolved, somehow our initial impulse for “connection” seemed useful, although not quite clear as to who and what. What was a constant preoccupation was the “disconnect” between a community and large forces that predictably were already aligning to shaping the future of Beirut including Gemmayze and the adjacent port. Of particular importance in our discussions was the possible connection between the initiatives of the “state” and those of the various NGOs and community actions that have quickly stepped in. It was also important that the studio’s work would not be seen as parachuting of ideas, but rather as a prompt for developing conversations around new planning interventions by local stakeholders and all concerned in the diaspora.

Perhaps such issues are endemic to Beirut history. Five millennia of continuous urbanity is an enormous legacy. Beirut has always moved beyond challenges, including the earthquake and tsunami of 551AD that wrought total physical destruction. There were lessons learned then and there will be now. From ancient times Beirut has been a crossroads, a place of global connection. We have assumed that it must remain as such, even as the globe changes.

Forward

Coming Together

Following the blast on August 4, 2020 in the port of Beirut, the GSAPP community came together and showed tremendous support to the Lebanese alumni as well as to everyone that was affected by the tragic event. In particular, the GSAPP Collective for Beirut was deeply moved to watch Professor Richard Plunz and Professor Victor F. Body-Lawson take on the colossal task of addressing the repercussions of this tragedy on the city and citizens of Beirut in a studio during the Fall of 2020. Centering a studio on this fragile subject to explore the ways in which the GSAPP community can respond to cities in times of crises is the heart and strength of the graduate program.

As part of our mission to harness the potential of a global network that is contributing to the development of Beirut, the Collective supported the studio, providing a critical lens for reflection and conversation. Through virtual engagement with the local community, the studio explored urban design issues, at macro and micro scales, in the area most devastated by the blast.

Through engaged discussions with students from various backgrounds, the Collective was deeply moved to watch students dedicate a full semester reflecting on sensible and impactful solutions that aim to support the Lebanese community in their physical - and emotional - reconstruction of the capital. The students’ commitment and level of engagement - especially during a stressful time of pandemic that halted any possible visit to Beirut at the time - are tremendous; they echo the complexity and thoughtfulness that went into every single project.

This report is by no means an end product. This is merely the beginning. The studio has aimed, and succeeded, in launching a conversation and providing seedlings for a framework that addresses the most recent crisis, as well as other lingering crises in Beirut. The Collective hopes to continue collaborating with Richard, Victor and the students and to explore ways in which this impactful report and conversation can reach the Lebanese community. Finally, we wish to thank every single person who has contributed to this report and who continue to make sure that what happened in Beirut on August 4, 2020 does not become a distant memory.

The GSAPP Collective for Beirut is an interdisciplinary alumni and student organization, founded organically in 2020, in the aftermath of the Beirut blast by a group of alumni and students. They studied asynchronously at Columbia University and are currently based both in Beirut and abroad (New York, London, Amsterdam, Toronto, Cairo, Dubai). The collective is fueled by matters, reflections and ideas related to current events in Lebanon, and the Middle East. Given the recent multiple crises in Lebanon, its initial focus is on Beirut while it addresses the local and regional context through its research.

About the Site

Planning Future Beirut: Learning from Two Centuries of Urban Complexity

It is challenging to describe Beirut to someone who has never been. In recent decades, the city has evoked imageries of war, violence and instability. Simultaneously, it has also flaunted infrastructures of hope, opportunity and growth. There are infinite historical, socio-economic, cultural and political layers to Beirut leading up to the port blast on August 4, 2020. By bounding the research on the impact of devastation to one particular area near the port – Gemmayze – the studio was able to wholistically address a fraction of the physical and emotional loss. In order to come full-circle with the design concepts suggested in each student project, the GSAPP Collective for Beirut finds it imperative to briefly include a short piece on the recent urban evolution of Beirut. While this piece is far from being a comprehensive account of the city’s complex urban histories that span centuries, the aim is to shed light, and appreciation, on some of the recent historical elements that had shaped Beirut up until August 4, 2020. Many facets of that Beirut that are embedded in the collective memory of its people may have been lost to the blast, forever.

A Prominent Port-city within the Ottoman Empire

Occupying a settlement site that is more than five thousand years old, Beirut is one of the most ancient cities in the world1 . However, its contemporary development only began in the early nineteenth century, when the port became a main transshipment point. By 1840, Beirut had 5,000 inhabitants and was considered a prominent port-city within the Ottoman Empire2 . As a central location for the transit of goods, its important status led to its rapid growth, turning the city into an important economic player in the region3 . Into the 20th century, Beirut retained its global importance as a hub for port-trade. By the beginning of World War One, the population had grown exponentially to about 130,000 inhabitants. Beirut was, by then, considered a central connecting point between Europe and Syria4 . The period between 1840 and 1916 is the time stamp that marked Beirut’s colonial heritage. During these decades, particularly between 1900 and 1916, the medieval city was partially razed as part of the Ottoman modernizing reforms 5 .

A Free-standing City following the French Mandate

With the defeat of the Ottoman empire in 1918, Lebanon and Syria were placed under the French mandate. Though the empire was partitioned, the mandate claimed to be different from colonialism in that France would only act as a trustee until inhabitants were ready for self-government. In 1920, Beirut became the capital city of Greater Lebanon. Under the rule of the French, the mandate continued with the “modernizing” policies that had already begun with the Ottomans 6 . Furthermore, the French transplanted a miniature of Haussmann’s planning for Paris onto the city center 7 . These plans to “modernize” the city indeed destroyed the old core of Beirut, paving the way for new road developments under the guise of modernity. By 1942, the country gained its independence from France. Lebanon was finally self-governing and Beirut was a free-standing city.

The Golden Years

The fleeting three decades of relatively stable independence between 1945 and 1975 that dubbed Lebanon the Switzerland of the Middle East. They were marked by strong economic liberalism, rapid demographic growth and major infrastructural development. Influx of capital from neighboring countries saw Lebanon on the rise, and investments targeted the real-estate and construction industries. Though the creation of the state of Israel in 1948 led to waves of displaced Palestinian refugees initially settling in the south, enticing economic opportunities in the capital between 1950 and 1970 increased rapid rural-to-urban migration 8 . Farmers, migrant workers and refugees moved from the hinterlands in the south of Lebanon, the eastern Bekaa valley, and from the northern towns into the capital. The administrative city became denser as new neighborhoods were created, and growing villages on the peripheries of Beirut were incorporated as extensions of the city. These included impoverished suburbs that extended beyond Gemmayze and the Armenian quarter to the east and into agricultural lands to the south 9 . Attempts at planning the development of Beirut could not limit real estate speculation or balance political and economic forces in favor of the city. As a consequence, continued rural to urban migration fueled the city’s “misery belt” during its thirty years of relative peace 10 .

A City at War with Itself

By 1975, Beirut’s population had reached over 1 million, and the city was already housing a quarter of the country’s population *. Though waves of Syrian migrant workers and Palestinian refugees were coming into the city for the industrial and agricultural sectors, it was evident that the Lebanese economy, in fact, relied heavily on its service sector to thrive. The state had adopted a laissez-faire attitude towards the market, rarely intervening to improve housing conditions 11 . During the fifteen-year-long Lebanese civil war between 1975 and 1990, the state lost much of its power. Services were considerably reduced, with the majority of social, economic, political and administrative structures destroyed. The war shattered vital networks of water, electricity, telephone and roads, and damaged around 300,000 households (Fawaz and Peillen, 2003)12 .

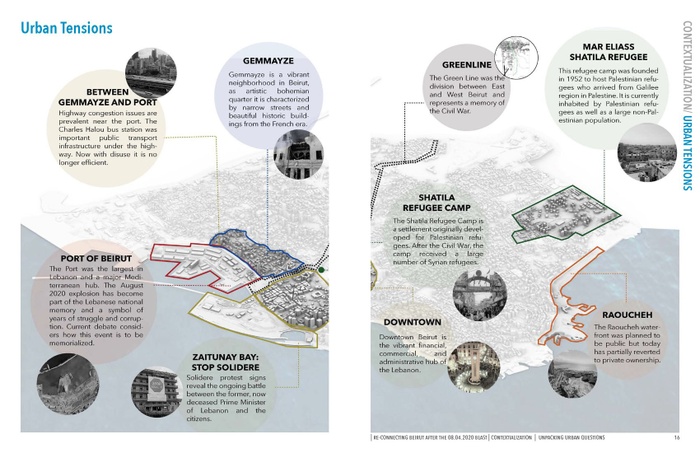

Geographically, the city was divided into two spatial entities: inhabitants in the east were predominantly Christian and residents of the west predominantly Muslim. Each side was run by rival militias. The heart of Beirut, spatially and symbolically at the center of the divide was completely deserted. The area soon came to be notoriously known as the Green Line, acquiring its infamous label after bushes and shrubs sprouted from its tarmac following years of abandonment13 . Such abandoned neighborhoods and empty buildings became repurposed as accessible housing for the waves of rural migrants and refugees. These population movements generated a new urban geography for Beirut as well as for its suburbs, which only grew denser14 . Much of the growth at the time occurred illegally, in violation of building codes, construction codes, and property rights regulations. The informal and illegal war-economy flourished, significantly impoverishing Lebanese households, reducing the middle class and worsening already existing income differences15 .

A Post-conflict City that Never Healed

The reconstruction of Beirut and its suburbs began in 1991, essentially under private initiatives. The most controversial project was the reconstruction of the city center, which had been entrusted to the public-private venture – Solidere – under the direct guidance of the late Prime Minister Rafik Hariri. The state had also launched other large-scale infrastructure projects. However, salient planning issues including public transit, low-income housing, and public space were not addressed. On the contrary: such large infrastructural projects of “reconstruction” included plans for highways that cut through dense neighborhoods, ensuing significant disruptions in the urban and social fabrics of an already delicate post-conflict city. Many of these projects led to the displacement – yet once again – to hundreds of families. By 1996, economic activity had substantially slowed down, due to the crisis in the real estate and construction sectors within a politically unstable region. Furthermore, the volume of debt had significantly increased, owing it to incompetent and short-sighted state leaders and war lords. By the year 2000, the country debt had reached over 30 billion US Dollars…

The Present City in Tumultuous Unrest

Over the last two decades (leading up to August 4, 2020), the country continued to witness a succession of political changes and violent disruptions. In May 2000, the last Israeli troops pulled out of southern Lebanon, ending the Jewish state’s 22-year occupation. In February 2005, the former prime minister Rafik Hariri was assassinated along with 21 others by an explosives-packed van that devastated the waterfront of the capital. In the summer of 2006, Israel waged war on southern Lebanon and Beirut, by land, air and sea, destroying a significant portion of the country’s infrastructure and devastating the southern suburbs of the capital. The years that followed saw a series of political assassinations of anyone with a voice, and in 2008 Lebanon witnessed the worst internal violence since the civil war, with pro and anti-government supporters taking to the streets.

Most recently, with the neighboring Syrian civil war entering its tenth year of conflict, Lebanon has become the host of the largest number of refugees per capita in the world. Many Syrian refugees navigated a harsh housing market, constructed informal shelters, doubled-up or lived in substandard structures in and around the city. Sheltering in or near Beirut provided their sole lifeline to economic livelihood in a country that has not always been welcoming. Many Syrian refugees sought networks of previously existing Syrians in Beirut, with a large portion settling in Nabaa16 , less than a mile away from Gemmayze. Many refugees and migrant workers – of Syrian and other nationalities - sought work in Gemmayze and the surrounding neighborhoods; as building concierges, cooks, cleaners, servers in restaurants, house keepers, construction workers and delivery people, among other occupations.

Planning Future Beirut

Laying out the historic milestones, and disruptions, of Beirut’s – and Lebanon’s – recent urban evolution further highlights how extremely challenging it is to envision a future that is bright[er]. Tracing this succession of events highlights that the August 4, 2020 blast not only blew up the port and Beirut’s link to the world; but the blast murdered 220 people, injured over 650, and displaced more than 300,000 persons overnight. The blast also imploded the centuries-long urban, historic, social and economic complex network of Beirut’s identity. The blast shattered the past memories, current dreams and future hopes of affected Lebanese families. The blast also stripped some of the most vulnerable and marginal communities - refugees and migrants living in the city - from their livelihoods, their homes away from home, and their fragile networks of survival as well. How can Beirut focus on healing, growth and togetherness when all odds throughout the centuries seem against it?

Indeed, the current situation looks grim, very grim, especially with the alarming economic crisis and during a time of global pandemic. It is challenging, and painful, to see past the fog. However, our focus must be on the reinvention of Beirut that is somehow underway. This essay hopes that by laying out the recent urban evolution of Beirut, we can perhaps envision - and hopefully better plan - the next decade. Having “no plan” as seems to be the current case for many, is in effect “a plan.” Though feeling hopeless and helpless is absolutely legitimate given the current climate, we cannot succumb to a laissez-faire position, as this presents colossal risks within the current turbulence. Beirut, beyond being a prominent port-city, was a place of conference, a place of mixing, for centuries. Beirut rose from the ashes numerous times in the past. It can rise again. In today’s world, the priority challenge is reconnecting Beirut to the world and reconnecting Beirut to its people. The hope is that these studio strategies help envision seeds, conversations, and hopefully plans, for Reconnecting Beirut.

Maureen Abi Ghanem is a doctoral student in the Urban Planning program at GSAPP Columbia. Her research focuses on investigating the socio-spatial impact of forced displacement and urban refugees on cities in the Global South, with a focus on Lebanon. Maureen holds a Bachelor of Architecture and a Master’s in Urban Design from the American University of Beirut (AUB). Prior to joining the PhD program, she worked in architecture and real estate firms in the Middle East. In 2014, Maureen joined the Shelter sector at UNHCR-Lebanon and managed the rehabilitation and access to affordable housing for refugees and vulnerable communities impacted by the Syrian war.

Naccache, Albert Farid Henry. “Beirut’s memorycide.” Archaeology Under Fire: nationalism, politics and heritage in the Eastern Mediterranean and Middle East (1998): 140.

Fawaz, Mona, and I. Peillen. “Urban slums reports: the case of Beirut, Lebanon (Understanding Slums: Case Studies for the Global Report on Human Settlements).” UN-Habitat, Development Planning Unit (DPU) and University College London (UCL) (2003).

Fawaz, M (1964) ‘Beyrouth, une Porte du Moyen-Orient’ Unpublished thesis, Institut d’Urbanisme de l’Université de Paris, France.

Fawaz, Mona, and I. Peillen. “Urban slums reports: the case of Beirut, Lebanon (Understanding Slums: Case Studies for the Global Report on Human Settlements).” UN-Habitat, Development Planning Unit (DPU) and University College London (UCL) (2003).

Saliba, Robert. “Historicizing early modernity—Decolonizing heritage: Conservation design strategies in Postwar Beirut.” Traditional Dwellings and Settlements Review (2013): 7-24.

Tabet, Jade. “Beyrouth, Collection “Portrait de ville”.” Institut. Français d’Architecture, Paris (2001).

Saliba, Robert. “Historicizing early modernity—Decolonizing heritage: Conservation design strategies in Postwar Beirut.” Traditional Dwellings and Settlements Review (2013): 7-24.

Tabet, Jade. “Beyrouth, Collection “Portrait de ville”.” Institut. Français d’Architecture, Paris (2001).

Beyhum, Nabil. “Espaces éclatés, espaces dominés: étude de la recomposition des espaces publics centraux de Beyrouth de 1975 à 1990.” PhD diss., Lyon 2, 1991.

Tabet, Jade. “Beyrouth, Collection “Portrait de ville”.” Institut. Français d’Architecture, Paris (2001).

Tabet, Jade. “Beyrouth, Collection “Portrait de ville”.” Institut. Français d’Architecture, Paris (2001).

Fawaz, Mona, and I. Peillen. “Urban slums reports: the case of Beirut, Lebanon (Understanding Slums: Case Studies for the Global Report on Human Settlements).” UN-Habitat, Development Planning Unit (DPU) and University College London (UCL) (2003).

Khalaf, Samīr, and Philip Shukry Khoury, eds. Recovering Beirut: Urban design and post-war reconstruction. Vol. 47. Brill, 1993.

Tabet, Jade. “Beyrouth, Collection “Portrait de ville”.” Institut. Français d’Architecture, Paris (2001).

Baz, (1998) ‘The macroeconomic basis for reconstruction” In: Rowe, Peter C., Peter G. Rowe, and Hashim Sarkis, eds. Projecting Beirut: episodes in the construction and reconstruction of a modern city. Prestel Pub, 1998.

Fawaz, Mona. “Planning and the refugee crisis: Informality as a framework of analysis and reflection.” Planning Theory 16, no. 1 (2017): 99-115.

About the Site

A Day of Living in Gemmayze

Gemmayze is a neighborhood in the Ashrafieh district that borders the no man’s land that split Beirut into two warring segments during the Lebanese civil war. Emerging out of the terrible war, Gemmayze quickly exploded with life, embracing a unique character of fully amalgamated cultures that is the magic of Gemmayze: the young meet the old, modernism walks side by side with the traditional, and sizzling nightlife fades out to give way to the chaotic business workday. Continuously, Gemmayze is energized by new activities from commercial shops opening early in the morning to restaurants, pubs and bars closing early in the morning, just like runners handing off the baton in a relay race. Everybody is alive and running in Gemmayze, it is the go-to place at any time of the day.

People reside in apartments right above pubs, pharmacies exist next to butchers, cafes are wall to wall with the police station, a small hospital is squeezed between French colonial two-story buildings. The scale is like a village, with narrow streets that stand in contrast to much of modern Beirut. The public space is intimate, knit together with the spine of Gouraud and Pasteur Streets and with the Saint Nicolas Stairs that serves as a spatial and cultural node. The built fabric is dominated by the sense of diverse heritage that reflects the same sensibilities as the intense diversity of activities that the buildings have embraced over the years.

Gouraud and Pasteur Streets are loud and busy, overrun with angry drivers that believe that honking their car horns repeatedly will somehow dissolve the traffic jams; neighbors screaming to one another with enthusiastic greetings; the constant roar of generators that seem to be working most of the day; construction and renovation sites on both sides of the streets. All around, electricity/telephone cables fly overhead zigzagging along building facades while pedestrians rush in both directions on very narrow sidewalks. Aroma of coffee and zaatar fill the street attracting passersby into coffee shops and local spots. Some occasional beggars pop up along the streets: young, old, more desperate as bad times prevail. This is my Gemmayze; this is the Gemmazye I have learned to love.

My day begins with a large pot of coffee, sobhiyeh and breakfast with my family, and the beautiful Beirut Port sea-view from our balcony. Sun rays sparkle through the windows to awaken up our senses to the people below filling up the streets and the church bells resonating in the background. What a nice way to start a day! The sobhiyeh passes by quickly, and it is suddenly time to start work. Since the breakout of the COVID-19 andemic, I have been working from home, which allowed me to appreciate Gemmayze even more. After lunch, I put my baby boy, Simon, in his stroller and hit the neighborhood for my daily walk. I usually walk towards the Saint Nicolas stairs where most of my favorite spots are. Along the way, I enjoy peaking at the art and fashion stores. Ahead, one of my preferred coffee shops prepares my usual daily order that I happily grab on the go and start sipping the fresh coffee while strolling down Gemmayze. Some days, I stop at the market to pick up some of our favorite local products on the way back home and have them ready for our afternoon snack or dinner.

During our walks, we encounter a few parents and babies that also stroll down Gouraud Street for amusement. We either pass by them or, most times, start a conversation while the babies exchange smiles and astonished long gazes with a waving “Hi” greeting. Along the way, all sorts of people stop by us and say something nice to Simon or gently give him a smile. We stop by the Saint Nicolas Stairs, sitting there for a while to have our coffee and snack while enjoying the surrounding noise and setting in this, one of the most unique public spaces in Beirut. Some residences, restaurants and bars line the stairs down from Gouraud all the way up to Sursock Street. Occasionally, these stairs are sometimes used for open air art exhibitions as well as public cultural events. Gemmayze is home to many art exhibitions that also take place in small galleries and shops, that give this neighborhood a hip atmosphere and a touch of romance.

The presence of food is everywhere. A go-to place of ours is a traditional Lebanese Armenian spot down Pasteur Street that serves exquisite fusion dishes. There are a lot of Armenian restaurants in the city, but this is by far the best we have experienced. It is always busy and almost always full. It serves a combination of flavors that never disappoint. We always take our out-of-town visitors to try it out. On the other end of Gouraud Street, a Japanese chef recently opened three authentic Asian spots that quickly became some of our go-to places. One of them serves the best Ramen in the city, another offers the only Japanese BBQ available in the city and finally the third serves the most delightful sushi selection.

Gemmayze also hosts one of the best meats and fish providers in the area. Although very pricey, when looking for high quality produce, I go and buy my favorite items. The quality never deceives us. With the ongoing economic crisis and the rising lack of available items in the market, prices have surged to an unaffordable level, even to its already existing customers. This is also happening to local shops and grocery stores which have tripled or quadrupled their prices. With the ongoing collapse of the Lebanese Lira in market value down from 1,500 to 15,000 LL to the US dollar, for the people getting their wages at the official country rate, which is still at the 1500 LL rate there is an alarming mismatch between the pricing of the items and their ability to purchase even the basics of food in a culture that takes great care about cuisine. Herein lies one of the most cruel aspects of what has come to pass.

Smack in the middle of Gemmayze, hidden behind a high wall, is Lebanon’s long closed main train station. Covering a sizable piece of land that could only be seen from third or fourth floor apartments. The huge train station hangers have been used for Christmas exhibitions and fairs while they remain idle the remaining part of the year to be used only by joggers and cyclists. As I walk past this station, I could not help but wonder why the government does not revitalize Lebanon’s train system as a much-needed public transportation mode, and especially now as maintaining a private car is becoming more and more prohibitive for most families.

Gemmayze’s strategic location and its rich mix of businesses, schools, restaurants, bars, hospital etc. allows its inhabitants to remain there for days if they so wish. This becomes obvious anytime I want to meet someone, and they eagerly request this meeting to be in Gemmayze, even at the expense of them travelling long distances. In everybody’s mind going to Gemmayze is an outing well worth the trouble. I believe that to best describe a day spent in Gemmayze, one needs to segment her day between a busy street in Paris, a restaurant strip in Nice and a residential street in LA, all mixed up together à la Libanaise. Gemmayze is unique; it is still my Home.

Nour Zoghby Fares is an architect and 2015 graduate of the Columbia University Urban Design Program. She is currently affiliated with the Beirut Urban Lab at the American University in Beirut (AUB) where she is Coordinator of the Critical Mapping Unit. Nour is also a part-time faculty at the Lebanese American University (LAU) as well as the co-founder of cras. collective research and architecture studio.

The Studio

1

Our NGO

THE STUDIO

This report challenges status quo planning protocols and suggests engaging the community in a discourse that could offer new ways of rethinking Beirut’s urban infrastructure in rebuilding in the aftermath of August 4 2020. Our work is represented under the rubric of a hypothetical NGO. Our intention is to suggest how our hypothetical NGO could deliver rapidly implementable emergency and long-term strategies for rebuilding and rethinking Beirut after the blast that destroyed major parts of the city. Our testbed focus is the Gemmayze neighborhood adjacent to the blast site in the port. Our Timeline as Provocation suggests a forecast of events that might counter the likely normative trends for rebuilding; by contrast we suggest provocations and alternatives, through micro interventions that could lead to a more promising future for the city and its people.

THE CATALYTIC MOMENT

On August 4, 2020 a substantial portion of Beirut was heavily damaged or destroyed by two explosions in the port; the second was of enormous magnitude, 4.5 Richter scale on ground surface. The explosion is said to be among the largest non-nuclear blasts in history. In a region of 2.4 million, 300,000 persons were displaced or otherwise directly affected; 110 buildings were totally emptied and the 15,000 persons lost their homes were concentrated among the 1.5 million population who are Syrian refugees. Within days, given pressure by citizen protests, the Prime Minister and Lebanese Cabinet resigned, leaving a caretake government of limited effectiveness. Extensive international aid was activated, including involvement of the United Nations and UN-Habitat. In our engagement, we were challenged by the notion that rebuilding could somehow challenge how planning has worked in the past.

THE SIMMERING BACKGROUND

Beirut is the major port city in Lebanon, on the southern Mediterranean coast. With 5000 years of continuous habitation, it is said to be one of the oldest extant cities in the world. In recent decades Lebanon has suffered political instability and a limited participatory planning process.

Since the early 1990s and after 15 years of civil war, the country missed several opportunities to rise from the ashes and instead moved from one crisis to the next resulting in increased civil unrest, lack of basic services, and growing poverty among its population. There was the early waste crisis in 1994 and ongoing to date. There were other infrastructural failures including the electricity shortages and the mismanagement and supply shortage of water services. All has been in the context of the questionable banking practices which have led to an idle economic sector evidenced in unemployment and immigration. Even before the blast, Lebanon has been left with a compounding of difficulties undermining its future. Ninety percent of its urban population lacks basic urban services and inadequate living environments. Political turmoil has led to system collapse that has predominantly affected an estranged low to middle income population known as the “dwellers of city’s suburbs in dense urban settings.” Lately these conditions have been coupled with the October 2019 uprising and the COVID-19 lockdown, also mostly affecting residents living below the poverty-line and facing ever increasing socio-economic uncertainties.

SITE

Our focus site is a section of Gemmayze Street in the Mar Mikhaël quarter and located 200 meters from the blast Ground Zero. It has sustained extensive damage, including many unsafe or collapsed buildings. It requires extensive rebuilding. A hub within our site is the famous Saint Nicholas Stairs, together and includes several other nearby nodes along the street to the east. The neighborhood was home to a mix of long-term elderly residents, together with younger group of engaged in entrepreneurship, arts, and other cultural production. In recent years Gemmayze became a popular destination for the entire city. Its fabric is comprised of a mix of “heritage” buildings, comfortable housing from the last century, and some more recent new construction. The ground floors tended to be dominated by a variety of commercial uses including restaurants.

MODE OF OPERATION

Apart our specific focus on rebuilding Gemmayze, our task has included rethinking the urban infrastructure of the larger city, addressing many of the problems that were present before the present day, from infrastructural inadequacy to social disjunction. Our team has been engaged with consideration of building strategies inclusive of the role of public space, within broader consideration of implementation. We are in dialogue with Beirut community stakeholders and have sought local professional advice. Through the lens of Gemmayze we have explored a strategy of micro-nodal deployment that can inform the development of similar approaches elsewhere in the city and region or possibly for other global cities facing similar challenges.

OUR APPROACH

Our hypothetical NGO will work to develop a system of microscale interventions complimentary to pre-existing and normative “top-down” planning strategies. Gemmayze serves as a testing ground for next generation “distributed” infrastructural approaches at the building cluster scale. Among our considerations were:

Pedestrian Connectivity. Rebuilding considers reconnection and reuse of public spaces for more inclusive social and economic integration including ease of access for all citizens.

Construction Materials and Technique. Consideration is given to reuse of rubble, sourcing of local materials, and collaboration with local labor. The proposed interventions aim to develop methods for the rapid deployment of building systems.

Clean Energy Production. Next generation photovoltaic is integrated with building-scale rebuilding and considered essential to the future of the city.

Water Harvesting. Given scarcity of water resources as a concern for many years, rainwater collection at the building scale is a primary consideration.

Housing and Health Services. Provision of a range of options for health services is an integral emphasis for public space considerations, including options for temporary facilities during the global COVID-19 pandemic and beyond.

OUR NETWORK (Stakeholders, Collaborators, Participants)

The public service considerations associated with our proposals prioritize a population in distress. As such our priority has been to explore concrete and realizable suggestions. We have attempted to engage a realistic set of program constraints and a broad group of stakeholders, including organizations who are directly involved with developing and implementing strategies for rethinking and rebuilding the city.

Beirut Studio Reviewers & Consultants

Amale Andraos, Dean, Columbia GSAPP

Hiba Bou Akar, Urban Planning, GSAPP

Michael Bell, Architecture, Columbia GSAPP

Viren Brahmbhatt, Architecture, City College

Filiep Decorte, UN-Habitat, New York

Michele Di Marco, WHO Téchne Network

Makram el Kadi, Architect, Beirut

Nour Zoghby Fares, Beirut Urban Lab (AUB)

Mona Fawaz, American University in Beirut (AUB)

Chris Ford, Center for Design Research, Stanford University

Richard Gonzalez, Architect, NYC

Jerome Haferd, Architecture, City College, GSAPP

Mona Harb, American University in Beirut (AUB)

Ziad Jamaleddine, Architecture, Columbia GSAPP

Elie Mansour, UN-Habitat, Beirut

Candice Naim, Architect, Beirut

Tarek Osseiran, UN-Habitat, Beirut

Roula Salamoun, GSAPP Collective for Beirut

Michael Shanks, Archeology, Stanford University

Yuka Terada, UN-Habitat, Nairobi

Serge Yazigi, American University in Beirut (AUB)

Maria Paola Sutto, Earth Institute Urban Design Lab

GSAPP Collective for Beirut

Aya Abdallah (New York) M.ARCH ‘22

Maureen Abi Ghanem (New York) UP PhD '24

Aude Azzi (London) M.S.AAD '18

Omar Bacho (Beirut) M.S.AAD '18

Charles El Hajj (Toronto) M.S.AAD '14

Mayssa Jallad (Beirut) M.S.HP '17

Dina Mahmoud (New York) M.S.AAD '14

Mickaella Pharaon (New York) M.ARCH '22

Maya Rafih (Cario) M.S.AAD '11

Roula Salamoun (Beirut) M.S.AAD '11

GSAPP Spring Research Seminar Professors

Victor Body-Lawson

Richard Plunz

Research Assistant

Yasmin Ben Ltaifa M.Arch '21

Contributors

Marie Christine Karim Dimitri M.S.AAD '21

Ali El Sinbawy M.S.AAD '21

Junyong Park M.S.AAD '21

Cheng Shen M.S.AAD '21

Zihan Xiao M.S.AAD '21

GSAPP Fall 2020 Studio

Fahad Al Dughaish M.S.AAD '21

Yasmin Ben Ltaifa M.Arch '21

Ali El Sinbawy M.S.AAD '21

Gabriela Franco M.S.AAD '21

Mia Mulic M.S.AAD '21

Junyong Park M.S.AAD '21

Aaron Sage M.S.AAD '21

Cheng Shen M.S.AAD '21

Ziang Tang M.S.AAD '21

Xian Wu M.S.AAD '21

Zihan Xiao AAD '21

Contextualization

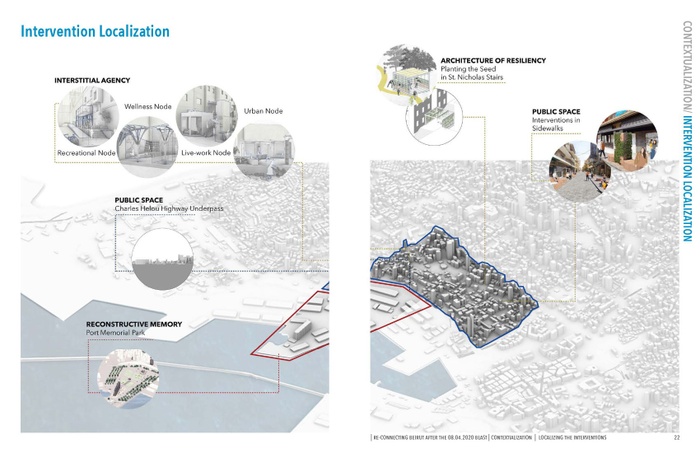

En•tro•py /’ entr pē/ is often interpreted as a degree of disorder or randomness within a system. It is used to represent lack of order and predictability. In the context of our research, when the country is in a state of instability, the entropic timeline is increasingly resulting in a positive entropy or increasing decline into disorder. Consequently, the question of time as a tool for healing is indispensable. The proposed timeline projects a more optimistic future for Beirut and a state of decreasing entropy. The difficult political and economic struggles that the country is undergoing have made it difficult for stakeholders to take major initiatives in revitalizing Beirut. As response, our proposed interventions represent a form of urban acupuncture. The INTERSTITIAL, the SEED, the Public Space, and the RECONSTRUCTIVE MEMORIAL strategies are anti-entropic, and structured as a bottom-up approach encouraging diverse NGOs and community members to participate in the reconstruction process. The main objective of this research is to facilitate new avenues for dialogue by proposing an expanded range of development considerations for Beirut.

2

An Entropic Timeline

3

Urban Tensions

4

Hierarchy of Needs

5

Localizing Interventions

Modes of Operation

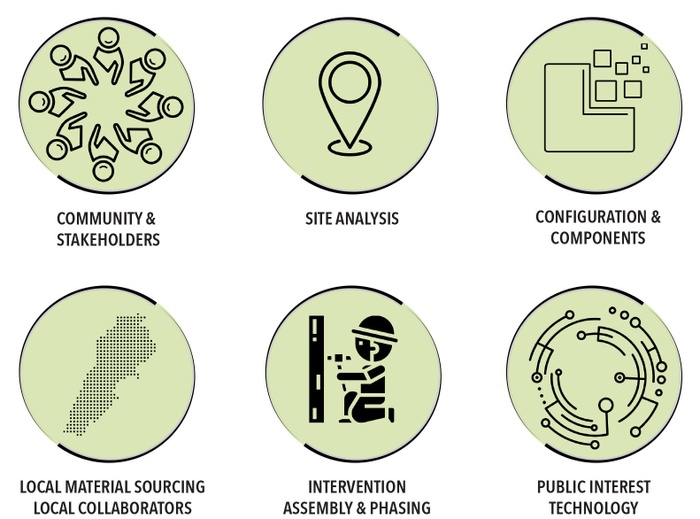

Identifying the hierarchy of project initiation and potential partnerships is essential in providing local agency in the Re-Connecting Beirut concept. Projects may originate from a broad range of stakeholders ranging from the public sector to the private realm. Re-Connecting Beirut follows a bottom-up planning logic that requires connecting those public, private and non-profit organizations working on the ground, potentially through Public Private Partnerships that reflect the public interest Suggested are Modes of Operation that include support of residents and landowners in providing essential infrastructural services including economic resources from the state, private investors, or donors. A proposed operational sequence would be initiated by community stakeholders, engage identification of intervention sites, provide sourcing for local material and labor, and assemble the project phasing plans. The potential of Public Private Partnerships lies most in the development of public space, where private partners would contribute to the construction cost and technical expertise for development of each project while benefitting from advertising, marketing, and management, for an agreed period of time and then turnkeying to public ownership. Applying this model would be facilitated by the proposed Digital Platform to maintain transparency and connectivity between the parties and ensure the involvement of public interest in the decision-making.

6

Modes of Operation

Modes of Ownership in Beirut

NGO Collaborators on the Ground

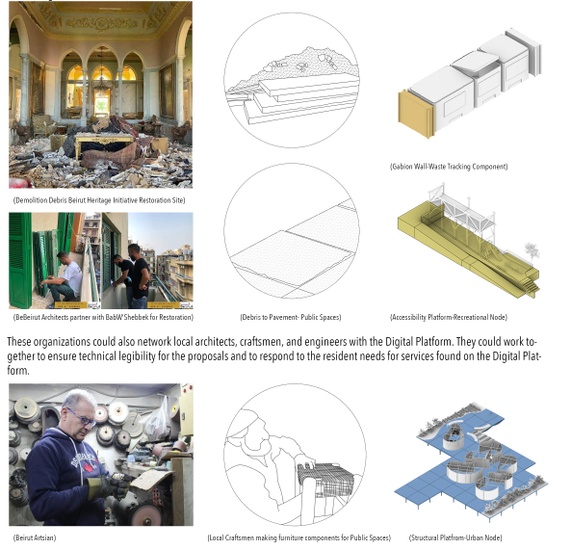

At present major NGOs and organizations are at work in Beirut with a primary focus on the post-blast restoration of homes and demolished historical buildings. Their work includes clearing demolition and blast debris, connecting residents to local architects and construction engineers for restoration purposes providing meals to those in need and addressing health-related issues like COVID-19 and injuries from the blast, and dealing with psychological consequences of the residents. Some of these organizations have been at work prior to the explosion with initiatives related to providing safer public environments for children and the elderly, providing healths services to residents and enhancing work opportunities for smaller local businesses. The list of NGOs keeps expanding, and we suggest networking these NGOs and organizations to increase local labor and material sourcing and maintain transparency and local agency during the reconstruction process.

7

Our Approach

The architectural project strategies summarized in this publication imply the need to follow a systematic and “bottom up” approach to adequately accommodate the Lebanese people’s most pressing needs in this time of distress. Consequently, defining community stakeholders has been key to defining an effective design process. Also crucial has been finding and analyzing appropriate sites, defining physical spatial characteristics that may help inform the reconstruction process. And design prototyping intervention components has been a crucial step, with careful attention to availability of availability of local material, constructors and community collaborators. It is anticipated that realizing many of these project strategies will require the help of local NGOs for construction. Ease of assemblage and construction constitute another critical consideration. Since these projects anticipated to be “bottom-up” the community or volunteers would also partake in further developing this work, abetted by the integration of social communication technology to provide additional agency to the communities. Public interest technology must help to enable future flexibility of programming while attracting multi-generational community participants.

Re-Connecting Beirut

8

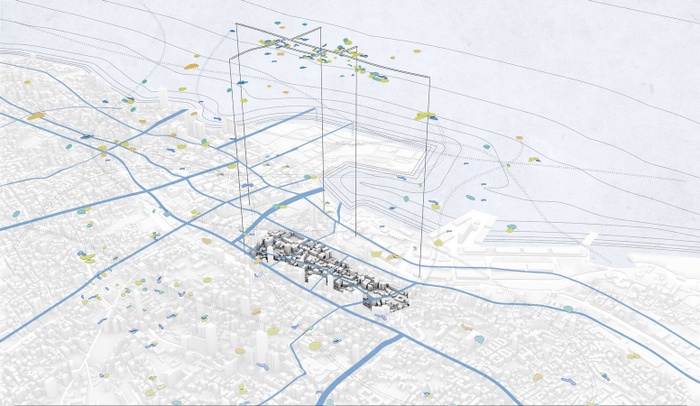

Urban network

Only 0.5 percent of Beirut neighborhoods comprise formally designated public space, making it a scarce resource and inaccessible to most. Following this logic, Re-connecting Beirut suggests a series of new spatial networks, that could increase connectivity and accessibility. The proposed architectural interventions follow a strategic localized approach that can assist in discussion of real needs by local stakeholders. This urban network concept will reconnect Beirut through micro interventions that aim to stitch public space into the urban fabric through essential infrastructural services. In Gemmayze, activating the informal interstitial spaces and expanding formal public space can help as a catalyst for reoccupation. To reclaim public space for the residents, sidewalk extensions on Gemmayze street are proposed to host commercial and public events that can promote social gatherings and facilitate accessibility. The interstices can form a pedestrian network of nodes that complement the formal public spaces, while offering essential services like housing, recreational areas, and public services together with necessary infrastructure like water, energy and broadband. The architectural interventions aim to connect to the heritage of Beirut with modest means like scaffolding, frames, and cladding materials that are appropriated to fit the local cultural context. Material sourcing and labor for the construction of the urban and economic network would be locally sourced in collaboration with workers, craftsmen and NGOs that connect to local architects, construction firms and workers. Re-connecting Beirut requires both physical intervention and community engagement in decision making. To promote transparency and communication, a digital network is introduced as a public platform, where the residents can participate in the process of the nodal development, thus adopting a bottom-up planning approach that provides equity and local agency to all Beirut communities. Re-connecting Beirut aims to reoccupy Gemmayze and activate the rich neighborhood economic network in the short term, while in the long-term providing a network concept that can be applied to other neighborhoods expanding on the potential of unutilized interstitial nodes and public spaces.

Ben Ltaifa - El Sinbawy - Park

The “Urban Platform Node** is a public space located above existing parking on the site. The public program provides green space for urban farming for residents. It is a lightweight architectural intervention constructed with a scaffolding/frame and clad with locally-sourced mesh fabrics. The platform can host small businesses, micro-markets and eateries, and local events. The arrangement of the architectural components within the open space can be determined by the residents of the neighborhood through the digital network following density and programmatic constraints.

9

Pedestrian network

The Recreational Node is located in a Type C informally gated space with a linear configuration. The Recreational Node can provide essential services for the residents of the surrounding area, to be determined by the residents themselves with the use of the Digital Platform. Essential services like water, and electricity are provided through scaffolding structures, with a public space platform and an ADA ramp added to provide accessibility to the area behind. The public space can accommodate a small playground underneath, to provide a safe, visible area for children to play. Terrace scaffolding can provide access for units that do not have direct connection to public space.

Micro-Intervention: Sidewalk Extension and Furniture

Micro-Intervention: Sidewalk Extension and Furniture

Micro-Intervention: Sidewalk Extension and Furniture

Sidewalk Extension and Furniture

The public space sidewalk extension project aims to intervene in Gemmayze at the intimate street scale. Given that Beirut has only .5% of its area formally dedicated to public space, the proposal envisions democratization by claiming more public space through prohibiting vehicular street traffic and enabling sidewalk extensions for commerce and other public activities to promote social gathering and accessibility. In Gemmayze a new pedestrian zone will activate a series of vacant lots and will engage the bottom entry of the Saint Nicholas Stair, promoting social interaction, community belonging, and new commercial activities.

Micro-Intervention: Sidewalk Extension and Furniture

Micro-Intervention: Sidewalk Extension and Furniture

10

Economic network

Micro Intervention: Live Work Node

Micro Intervention: Live Work Node

Micro Intervention: Live Work Node

The Live-Work Node is an interstitial addition to housing in Gemmayze. The Node is composed of prefabricated frame structures that vary in size and shape according to the spatial requirements of the empty plot on site. The units are meant to house displaced residents’ post-blast in the short term and would then evolve to spread out through the site to house artists, entrepreneurs, and workers on site. The Live-Work concept would come more in the later stages where the unit would have a living space, a small office/workshop and an open public space that connects to the side streets and the courtyards between buildings, and thus would create more vibrant side streets and voids between buildings.

The Live-Work Node is an interstitial addition to housing in Gemmayze. The Node is composed of prefabricated frame structures that vary in size and shape according to the spatial requirements of the empty plot on site. The units are meant to house displaced residents’ post-blast in the short term and would then evolve to spread out through the site to house artists, entrepreneurs, and workers on site. The Live-Work concept would come more in the later stages where the unit would have a living space, a small office/workshop and an open public space that connects to the side streets and the courtyards between buildings, and thus would create more vibrant side streets and voids between buildings.

Micro Intervention: Live Work Node

Micro Intervention: Live Work Node

Micro Intervention: Live Work Node

11

Digital network

Public Engagement

Public Engagement

The Healthy City

A Healthy City is a neighborhood based on smart strategies that engage resiliency, flexibility, adaptability and mobility. A Healthy City responds not only to health imperatives but it must anticipate other community needs. To succeed, it requires both private and public initiatives in order to build a network of localized systems that include Wellness Node together with energy and water collection systems, food production systems, economic and social service systems. During a pandemic the health infrastructure must respond quickly and with flexibility. The Wellness Node must adapt from testing place to vaccination place to visitor spaces adjacent to the outpatient clinic, to handwashing station. It can also engage environmental initiatives related to air, water, energy, food and social networking. Micro-infrastructure modules can be tied to the larger public health system engaging energy and water, food production, broadband services. Residents can receive transparent, systematic and equitable access to the distribution of public health services, public information, and public education within the same system. The Healthy City will decrease entropy through a network of Nodes that can raise people’s awareness and expectation of a flexible, transparent, accessible, equal and healthy future of the city.

12

Wellness and the COVID-19 Pandemic

Micro-Intervention: Wellness Node - Pandemic and Blast

Micro-Intervention: Wellness Node - Pandemic and Blast

Micro-Intervention: Wellness Node - Pandemic and Blast

Micro-Intervention: Wellness Node - Pandemic and Blast

Micro-Intervention: Wellness Node - Pandemic and Blast

Micro-Intervention: Wellness Node - Pandemic and Blast

Micro-Intervention: Wellness Node - Pandemic and Blast

Micro-Intervention: Wellness Node - Pandemic and Blast

13

Growing the City

Micro-Intervention: Growing the City

Micro-Intervention: Growing the City

Micro-Intervention: Growing the City

Micro-Intervention: Growing the City

Micro-Intervention: Growing the City

Micro-Intervention: Growing the City

Micro-Intervention: Growing the City

Beirut residents have suffered from inadequate access to basic resources such as water, energy and food; now combined with the August blast and pandemic. The recent economic crisis has caused more than half of Beirutis to find themselves below the poverty line. The concept of “Seed” is a deployable module that acts as a host for activities and provides deployment resources including economic and social services to the community. It becomes a medium to grow community self-sufficiency. It can generate solar and motion energy, harvest water, and provide green produce for the community. Designed to be a flexible space assembled with readily sourced materials and reused material, the Seed allows the users to reconfigure urban space in accommodating differing programs or constraints. The Seed consists of modular parts that can be assembled with limited tools and expertise across multiple neighborhood typologies in residual spaces such as vacant lots. The Seed can be used as a fresh foods kiosk and productive greenspace serving both local restaurants as well as passers-by. It also can provide information, wifi, or other social services. In a pandemic, it can become a medical facility for Covid testing with its easily deployable curtain system. On a residential rooftop, the Seed can serve as a quarantine space for residents exhibiting mild symptoms. In non-pandemic situations, the Seed can be a garden space providing food for the building’s residents, as well as a workshop space. Deployed on Beirut’s sidewalks and stairs, the Seed can be integrated with areas of intense pedestrian traffic for a variety of purposes.

Next Steps

Engaging Local Networks

Our lexicon of micro interventions is intended to serve as a catalyst for discussion among the numerous local stakeholders engaged in the process of Re-Connecting Beirut in the immediate period of reconstruction. They are also intended to point to an expanded vision of planning for the future with provocations for jump starting fundamental change in the way communities like Gemmayze can collectively think about planning and design. Our approach grew out of detailed study of the context of the political events combined with the evolution of needs in Beirut in recent years. We assembled an illustrative series of “acupunctural” community design options that can respond to address the study of events and needs. These design concepts put forth in this report are intended to be speculative and not definitive, but rather to contribute to debate in the evolution of new planning concepts for the city. They are open-ended and leave much room for interpretation and adaptation, as reference for those tasked with taking action on the ground. We identify some local stakeholders and anticipate that there must be others, and we hope to have provided some fodder for positive change especially for those communities most affected by the blast as they struggle with their task of rebuilding.

Engaging Local Networks

NGOs, Collaborators & Stakeholders The need for collaborations between NGOs, community organizations, and other local stakeholders is an essential premise for our “Reconnecting Beirut” concept. We recognize the importance of maintaining local agency and transparency for localized projects inclusive of design, assembly, construction and post-construction maintenance, management, and equitable accessibility. Direct collaborations can include diverse partners in realizing our proposals:

1. NGOs Working on Restoration & Reconstruction There are multiple organizations on the ground that are assisting with restoration of damaged homes and historical buildings. Collaboration between these organizations could share material sourcing, including collected debris that would be used in the construction of the sidewalk extensions for additional public space and gabion walls and accessibility platforms for the proposed scaffolding interventions

These organizations could also network local architects, craftsmen, and engineers with the Digital Platform. They could work together to ensure technical legibility for the proposals and to respond to the resident needs for services found on the Digital Platform.

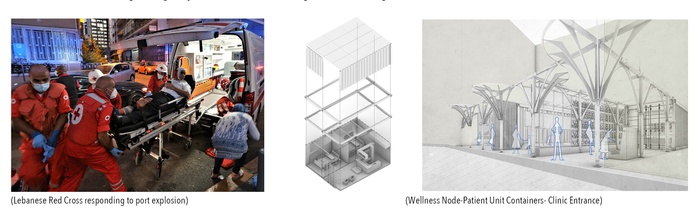

2. Organizations offering Healthcare Services

Among the many organizations offering healthcare services is the Lebanese Red Cross, Caritas Lebanon and Embrace. These organizations may collaborate with the Wellness Node proposals, where they would offer nursing and medical services to the residents using the health Node components as hosts. The Wellness Node components are moveable structures that can move around Beirut according to urgency levels and addressing the well-being needs of residents.

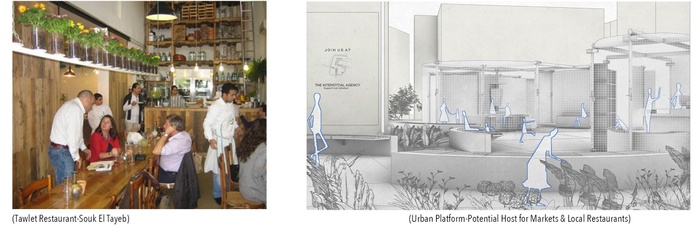

3. Organizations working with Local Businesses Organizations working with local businesses could include Tawlet, a Beirut restaurant that weekly hosts a different local Lebanese cuisine; potentially each week in coordination with the Urban Node platform and the sidewalk extension activities. Tawlet is managed by the same organization that initiated “Souk El Tayeb”, a food market specializing in Lebanese organic produce with the goal of bringing communities together to share food and local traditions. The proposed Urban Node platforms could act as a host that aim to promote the economy of such local business initiatives.

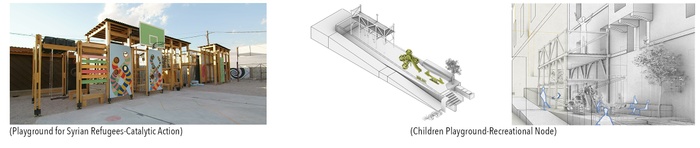

4. Organizations working with Childcare Initiatives for childcare are increasing in Beirut. The Lebanese-founded and London-based “Catalytic Action” recently designed inclusive playgrounds for displaced children, in collaboration with local factories for material sourcing and equipment. Collaboration with Catalytic Action could be used to add inclusive playgrounds for children in the proposed Recreational Node and other public spaces.

Commentary

Infrastructure As Accumulated Knowledge, Michele Di Marco

Architecture represents an accumulated knowledge, a tool that everyone has the right to use and therefore, if used properly, can be valuable to defend human rights. In different parts of the world and in different historical moments, architecture has been a driver for social change. Regarding health, history has shown us that in cities, infectious diseases are a major concern, synonomous with urbanization. The COVID-19 pandemic shares much with this history. In Beirut, like elsewhere in Europe, the pandemic will contribute to a defining moment in the long history of the city.

There are many epidemic precedents in urban history. For example, the bubonic plague persisted in Europe for more than three hundred years, between the so-called Black Death of 1348 and the last major outbreaks in London of 1665 and in Marseille in 1720. It is believed that a third of the western European population died between 1348 and 1350. Urban mortality, as the result of infectious diseases, was a constant since the first half of the 14th century in European history: the death rate was estimated to be 60% in Genoa (between 1656 and 1657); 50% in Milan (in 1630), Padua (in 1405) and Lyon (between 1628 and 1629); and 30% in Norwich (in 1579), Venice (in 1630-1631) and Marseille (in 1720) (Slack, 1989).

Infrastructure design for epidemic control

In Beirut like elsewhere, the tools for social change must engage not only disease in isolation, but wholistic system. Again there are useful precedents. For example, in London the pyramid of epidemiological studies includes the discovery of the cause of the cholera epidemic that occurred in Soho during the autumn of 1854, where around 500 people died in only 10 days. The cause was infrastructural, discovered by Doctor John Snow, thanks to a series of interviews an analysis of water samples and elaboration of density mapping illustrated the spatial concentration of sick people. It was contaminated drinking water supplied from a pump located on Broad Street that caused the disease. With this research it was possible to understand the transmission mechanisms of the pathogen that caused the disease, and thanks to the architectural modifications made in the neighborhood it was possible to reduce the cholera incidence and mortality rate (Ramsay, 2006).

Even though hygiene problems were a constant in European cities, there were crises that provided important lessons and promoted the transformation of cities. One was social isolation. The quarantine has been an important social tool originating in the 14th century as a method to control the spread of the Black Death in Europe. Between 1348 and 1350, a pandemic caused the death of more than 50% of the population. Authorities were forced to take extreme measures to control the transmission. In Milan, for example, the Lord of Milan decreed the expulsion from the city of all infected persons; in Mantua it was ordered that persons traveling to areas with high mortality could not return, under pain of death.

In addition to social controls, new health infrastructures were invented. In the Republic of Venice in 1423 the first permanent hospital to care for people affected by the Black Plague, a lazaretto, was located on the island of Santa María. The name “lazaret” is associated with Nazarethum or Lazarethum, due to the relationship with the biblical story of Lazarus who was raised from the dead. In 1467, Genoa adopted the Venetian system of lazaretto, and in 1467 in Marseille, a hospital for people with leprosy was created. These facilities played an important role in reducing contagion during the Renaissance, since they allowed the separation between healthy and sick through correct isolation, as well as proper monitoring and control of the disease (Tognotti, 2013).

What will post-COVID-19 cities be like?

This year has caused a radical change in our lives, and it will have a great impact on the future of our cities. About 90% of COVID-19 cases have been reported in urban areas due to population density, living conditions, and the way we interact in cities. The impact of the pandemic has been superimposed on problems of security, work, transportation, health services and inequity in general. The most affected urban population lives in smaller spaces, on lower incomes. COVID has shown us that cities represent obsolete health systems that need to be renewed, because the urban population is the most affected by any type of catastrophe, whether natural hazards, pandemics, or wars. The present crisis leads us to question the place where we work; spaces where we live and the way we inhabit; the density and extension of cities and elements or parts that make up a city such as parks, public spaces, and streets. The explorations in this report provide useful new thinking about health infrastructure in the context of Beirut. With its endemic broad infrastructural dysfunctions Beirut is an important test bed for next generation infrastructural innovation.

For next generation health infrastructure we have learned much from recent crises such as SARS-CoV-2 that had a large effect on urban infrastructure and generated an even greater deficit in urban health systems. The COVID pandemic gives us the possibility of correcting these mistakes and, especially, favoring the rights of the most vulnerable populations.

With the pandemic, the consideration of a metropolis made up of self-sufficient and interconnected communities is timely, and the crisis is likely to be a catalyst for rethinking the distribution of urban densities at a global level. The studies for Beirut represented in this report give important clues. They show us the fragility of our planet and make visible the need for recreational spaces in our homes and streets. They are a harbinger that in the years to come, we will observe a change in architecture similar to what happened almost a century ago, when hygienist perspectives influenced modern design; when for fear of contagion of diseases such as tuberculosis, the construction of open spaces was promoted leading toward a transformation of the social use of buildings and cities.

Finally, the COVID-19 pandemic shows that structural urban inequity is what defines our epoch. For this reason, it is important to reflect on the post-COVID city. These studies reflect critically on the need for a fairer city, and envision building a future that recognizes the right of normal people to participate as a central catalyst in this process. A city is an ideological, social, and intrinsically political product. A city is built collectively and through a discussion between communities, technicians, and politicians. It is time to rethink questions and answers. Beirut can be an important catalyst in this global discussion about creating a healthier city.

A more equal and multidisciplinary approach to pandemics

This report illustrates the potential of the COVID-19 pandemic to inform the scope of environment transformations that have to take place in the next decades. It will be a task that single organizations cannot solve. It is for this reason that since April 2020 WHO has been building Téchne, the Technical Science for Health Network. This network, composed of universities, institutions and humanitarian and international nongovernmental organizations, works in collaboration under WHO leadership to develop technical interventions. The experts in the group have technical and academic backgrounds in architecture, civil engineering and mechanical engineering, among others. Its members cooperate with WHO on a diverse range of activities such as sharing specific technical knowhow, supporting Member States with ad-hoc requests and developing technical innovation to improve environmental and engineering controls as part of the strategies to reduce the risk of disease transmission.

Téchne is a unique and valuable resource that, with its multidisciplinary, highly specialized technical competencies and the free exchange of ideas, can play a key role in the current epidemic and for future emergencies in terms of technical support, research and development, education and innovations. Although conceived and developed to meet the operational needs emerging with the COVID-19 pandemic, it is now developing into a multidisciplinary group able to respond not only to epidemics, but also to prevent and minimize the health consequences of complex emergencies and natural hazards. We welcome Re-Connecting Beirut as an important contribution to our efforts at Téchne.

References

David, K. (1992). Yellow fewer epidemics and mortality in the United States, 1693-1905, Social Science and Medicine, 34(8), pp. 855-865.

Gensini, G. et al (2004). The concept of quarantine in history: from plague to SARS. Journal of Infection, 49(4), pp.257–261.

Halliday, S. (2001). The Great Stink of London. Sir Joseph Bazalgette and the Cleansing of the Victorian Capital.

GloucestershRamsay, M. (2006). John Snow, MD: anaesthetist to the Queen of England and pioneer epidemiologist. Baylor University Medical Center Proceedings, 19(1), pp.24-28.

Slack, P. (1989). The black death past and present. 2. Some historical problems. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 83, pp.461-463

Tognotti, E. (2013). Lessons from the History of Quarantine, from Plague to Influenza A. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 19(2), pp.254.259.

United Nations (2015). Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Geneva, United Nations Regional Information Center UNRIC. Retrieved from https://www.un.org/es/documents/udhr/UDHRbookletSP_web.pdf

Michele Di Marco is an architect specialized in disaster risk reduction and a founding member of Téchne, the World Health Organization Technical Science for Health Network, where he coordinates operations and activities.

Commentary

Is Planning the Reconstruction of Beirut Possible?

Serge Yazigi: It is an essential question. The August blast is challenging us to propose a new model of reconstruction. It is definitely not the one we used for the reconstruction of Beirut’s historic core after the civil war in 1994 with the Solidere’s corporate operation. Nor is it the one that was used for the reconstruction of the South of Lebanon of even the Southern Beirut’s suburbs, in the aftermath of the Israeli bombardment (August 2006) which, I believe, were mainly driven by politics.

When these previous reconstruction efforts started, at the Beirut Urban Lab (American University of Beirut) we feared that they would be NGO-led reconstruction; something like Haiti after the earthquake in 2010. The model remains unclear now and the situation has changed. The World Bank and the EU are pushing forward for a new framework focused on reform, recovery and reconstruction. For the first time, civil society organizations and academicians are invited to become part of this process.

Filiep Decorte: Why the reference to Haiti?

Serge Yazigi: Because you have various NGOs coming forward, one after the other, saying we have a program, we have a plan, we would like to intervene in this specific topic and within this geographic area, and so on. The challenge is how can one channel these fragmented efforts and mainstream priorities that really do correspond to the needs of the inhabitants and that inform response to the critical challenges of housing and public spaces. We need to ensure ownership and involvement of the inhabitants, knowing that funds are essentially external as domestic resources are unavailable due to the ongoing economic crisis.

Filiep Decorte: So what is the key thing needed?

Serge Yazigi: We need to ensure that the plans and funding add up much better to become a collective effort. We do need to push for reforms and a better governance model. In addition, we need to keep public institutions involved, even if the country is in the state of collapse.

Filiep Decorte: How does the reconstruction of the port fit in?

Serge Yazigi: I think it is not the same dynamic in the port as is taking place in the neighborhoods. In the port the private sector will have to step in through some kind of PPP (Public Private Partnership). There is currently however a lack of transparency of what is really being planned for this area. Every few weeks, we are confronted with some plan that is being leaked but not really fully communicated to the public. In addition, until now there is no comprehensive vision that integrates the port with its adjacent neighborhoods.

Filiep Decorte: Beirut is such a complex environment. It always has been and has evolved over time. There is no clear morphologic structure. It seems to have grown quite organically with some major infrastructure, such as the port, added as a random annex. The port is part of it and not part of it.

What is the function of planning in Beirut? Who has real planning authority and capacity for the whole of Beirut? I think the way governance is set up and is functioning, or not functioning in Beirut, makes it very hard to execute planning as a process in support of the public good.

Looking back in history, at the end of the civil war, the same question around planning came up as now after the blast; then around the need to reconstruct the old souks in downtown Beirut. It took a very strong coalition or even collusion between the public and a private sector for things to start happening. But it was not at all inclusive. There is a real challenge for any reconstruction planning process to be inclusive and transparent and collaborative; and that aligns the big efforts with the small efforts, with what happens at the neighborhood level.

It seems that there is an absence of a planning framework and a critical challenge going forward. The planning of the port seems to be separate from planning for the city. Who are the actors in Beirut that can actually ensure that the two are part of the same planning exercise? It doesn’t matter if it is bottom-up or top-down.

Serge Yazigi: Public authorities are relatively absent from the whole process. Many of us local planners call on the state to be involved. There is clearly a governance issue. Public institutions were not able to plan and manage sustainably the neighborhoods before the blast. And currently they are not in a better situation. In contrast, limited partnership with the private sector has occurred, as some entrepreneurs have funded several renovation projects. As for the port, it falls under the jurisdiction of a special authority that has shown, until now with limited will to collaborate with other public agencies, shall they be local or central.

Filiep Decorte: You were saying the World Bank and the EU are trying to advance a new approach to this port issue, focusing on the 3R’s: reform, recovery and reconstruction. UN-Habitat is fully engaged with this. The blast is not the first crisis. Beirut has been in a de facto protracted crisis for a while, with vulnerabilities that pre-date the blast. And yes, as you mentioned, governance is one of them. It includes the capacity for public authorities to execute their core functions of which planning is one. What complicates matters is that you have multiple layers of authority. Beirut is the capital with critical national infrastructure involved like the port. And at the same time, Beirut is broken down into smaller municipalities, with weak authority but they are the closest to the people. UN-Habitat is advancing the notion that in these kinds of situations, you need to develop a clear urban recovery framework. And the urban recovery framework goes beyond what we normally do, which is assessing what is damaged and what needs to be done, focused on physical reconstruction.

The EU and the UN are used to do assessment at the national level, following disasters. Beirut, however, is clearly demonstrating the need to also do this at the level of an urban area of a city. It is clear what the damage is. It is clear what needs to be reconstructed, but it is not clear how. There are two important dimensions to this challenge. One is the “how,” has to do with the institutional landscape; who can do what, and how do the efforts of different parts come together? There must be government, private sector, but also of course, communities, and small businesses, and actors like the universities should all be part of the institutional framework, recognizing what the capacities are of one on the other. It is critical for all forces to be combined and aligned, the big and the small. Secondly, there needs to be clarity on the vision, on what are everyone is working towards. In the process, we need to overcome some of the weaknesses of the past and work towards a more sustainable, resilient and inclusive future. Is it possible for a whole of society approach, to come together and have a clear, common understanding on the way forward? What is blocking it? This is not the last shock for Beirut and Lebanon.