Preface

Letter from the Editors

How will history remember the years 2020 and 2021? As the editors of URBAN Magazine, we constantly strive to frame our publication in a way that powerfully reflects the poignant issues of our time. From the COVID-19 pandemic, to racial equity, spatial exclusion, and beyond, these subjects, though often overwhelming, are crucial to discuss. We feel fortunate and privileged to have had the opportunity to read and reflect deeply on the pieces submitted to URBAN by our esteemed colleagues and peers.

In Fall 2020, we dedicated Dialogues to our community’s reactions and thoughts as we witnessed legacies of social and spatial injustice unfold across different geographies. Since the last issue, the Chauvin trial and the surge of anti-Asian hate crimes reminded us that a lot of work still needs to be done. The Spring issue, Reimagine, invigorates these continued conversations with hope and contemplates new norms for the built environment.

Reimagine captures how the past year has forced us to intensely rethink our personal and collective relationships with urban space. Contributions range from personal stories of the past year, to those envisioning new roles of public space, giving voice to historically marginalized perspectives, and suggesting new paradigms for a post-pandemic world.

Publishing URBAN during these tumultuous times has been a challenge. We offer our deepest gratitude to the writers who shaped this issue, junior editors Eve Passman, Will Cao, Shreya Arora, and online editor Sherry Te. It has been an honor and privilege for us to work with them to continue this long-standing, student-led, editorial magazine. URBAN would not be possible without the support of GSAPP and our community of readers. We hope that you, like us, find a moment to step back, reflect, and Reimagine.

Sincerely,

Senior Editors of URBAN Magazine

Tihana, Geon Woo, Zeineb

1

A Glimpse Into the Year

Source: Author

Mental health or quality of work? Which should I prioritize during graduate school in a pandemic? If I were to give myself advice as a friend, I would suggest to take care of your mental health first. However, taking that advice wasn’t as easy for me to apply during most of my graduate school experience, especially when COVID and other rattling and disturbing chronicles emerged.

I was hesitant to write about something so personal that could come off entitled. Why should I, a graduate student at an Ivy League, take up space to talk about my struggles during a pandemic? My hope is that the takeaway from my experience resonates with my community here, and that the countless virtual conversations I’ve had with many of my peers has a place to lie. My audience is anyone that would like to listen.

The trauma of this past year has been overwhelmingly high. Within the last year, students have faced tuition increases, excruciating housing insecurity, and mental health strains, none of which are new struggles, but have been exacerbated by the pandemic and the political climate. My international friends have had other struggles I have not faced. During the past summer, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) had opened a directive that would not allow international students to remain in the U.S. if they were taking online-only courses for the Fall 2020 term. Both my roommates, with whom I had just signed a new apartment lease, did not know if they would have to leave the country sporadically. In addition, graduate student workers continued their strike in demanding a fair contract and recognition as employees, with some of my cohort fellows and teaching assistants participating.

Along with housing and financial stressors came mental health and other health-related concerns. My peers have gone through their own stressful moments. One person told me of a time they were yelled at by a professor via email at the beginning of the Spring 2020 semester for missing the first class because they had scheduled their flight from China on that day even after explaining the situation. Trips have been scarce and expensive, and finding a time that worked to get to the U.S. was a journey on its own. Others told me that they had given up, “Elaine, I have no more motivation and honestly just want to be done with grad school.” Many shared their experiences of being back on antidepressants, and I too have had a conversation with my doctor asking how it could help my own anxiety.

As a member of the Program Council, myself along with a few peers have tried to put together events to allow our cohort to feel more connected, which is a difficult task considering that we are scattered across the globe. We decided to create a newsletter exclusively for our classes. We called it the UP Digest. It is a place where folks can share and learn from each other, a free formed newsletter for more intimate conversations. Mid-semester, we received an anonymous submission through our form: “I need someone to tell me I am not the only one struggling with online learning, thesis, believing that I will actually finish the program. The school is not accounting for our mental health / mental strain from online learning…”

Another submission we received was, “I am frustrated with online learning and have hit my wall. I am no longer interested in courses, or my thesis, and I have no idea how I will get everything done. I move between stressed, disinterested, anxious, tired, and sullen. This is not sustainable.”

Hearing these messages from my peers was difficult because there was no one thing to say to make anyone feel that much better. The only thing I felt like I could say is: “you are not alone in this…” I wish I could do more.

On top of the mental health of our students, it would be wrong not to recognize that loads of work combined with high expectations from professors became added stressors. The student-teacher relationship broke in many ways. It was hard for me to face my professors when, in all honesty, I had given up too. During one personal interaction with a professor, I felt like crying. I did my best to hold it together, but after leaving the Zoom chat, I bawled. The balance between keeping a healthy mental state and the expectations of an education at an institution full of talented and intelligent communities had collapsed. The stress induced by my professors’ expectations, crossed with my own falling determination, was a tragic mix. It was even more depressing knowing that graduate school, which used to be a source of great joy for me, became something I dreaded so much.

Adding onto the mental health strain, the Asian community has also been through escalating racial attacks throughout the past year. The recent massacre in Atlanta had been so prominent for me. I continued “doomscrolling” the news; I was distracted, disturbed, and wanted to have time to mourn. It felt wrong having to set those thoughts aside to focus on submitting the penultimate draft of my thesis. The fact that I could do so was a complete privilege.

As my fellow classmates push through this semester with every last fiber of energy, I’m unsure if there are any more words of encouragement to give. What I do know is I can share and ensure our story is acknowledged and recognized so that future administrators, professors, and graduates may learn from our struggle and find better ways to nurture one another. I believe that prioritizing the mental and physical health of our students, over purely academic success, would enhance the graduate school experience.

I do believe the administration and my professors are trying their hardest to be empathetic, patient, and realistic with the conditions of a pandemic, with many of the mentioned circumstances being out of their immediate control. I only hope that the compassion shown during the midst of this crisis will continue to uphold. The trauma from this year will not have faded by Fall 2021, nor by Spring 2022. As I mentioned in the beginning, these issues have always existed, and are now so obvious they demand to be reckoned with.

2

Civic Engagement in Physical and Digital Public Space

On June 2, 2020, over 28 million Instagram accounts posted a black square for #BlackoutTuesday as an act of solidarity with ongoing protests against police violence in the wake of George Floyd’s murder (Monckton 2020). Throughout the summer, the Black Lives Matter Movement gained traction like never before by protesting not just in a physical public space but in a digital public space as well.

Since the Greek Agora, public space has played a key role in the development of cities. They offer citizens places to meet and engage in meaningful discussion (Carmona et al. 2008). Around the world we have seen people from all walks of life come together in these spaces and use them to protest. People protest against their oppressive governments, against their political leaders for not doing enough to prevent climate change, against police violence, and march for their basic human rights.

The rise of social media activism has led to a new way of protesting that can draw more attention to a movement, and involve people from all around the world that support the movement but could not otherwise be able to attend protests in person. Instagram, Facebook, Twitter, Reddit, and now TikTok are reshaping how we amplify our voices and make change; these channels give ordinary people power beyond the public space as we have known previously. Social media platforms offer a complementary approach to civic engagement that can make involvement in protests and movements more accessible, and, thus, create a bigger impact.

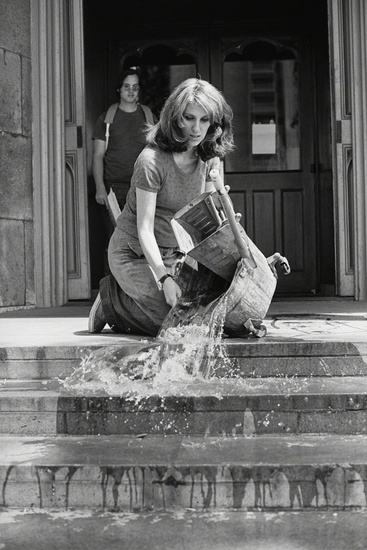

At physical protests, crowds often show up and march, waving their homemade picket signs, or participate in boycotts and sit-ins. People will echo chants and give speeches. Other times they will be silent. Despite what the media may have us believe, there is no wrong way to protest. At the end of the day, it is about being heard. Above all else, the significance of the place is the make or break feature of a protest. In Los Angeles, for example, low density has led to protests taking place on highways rather than in the city itself, because they block traffic and force people to acknowledge what is going on (Schwartzstein 2020).

Social media offers us a new way of looking at the significance of place. With something as simple as a hashtag or mention, a small group, or even just one person, no matter where they are in the world can start a movement. In the summer of 2020, I watched social media accounts shift to be more civically active; sharing information and graphics from activists and writing captions that declared their political beliefs. I saw celebrities like Olympic Steeplechaser Colleen Quigley share their accounts with people of color for the day, to share their story with a different audience in “Pass the Mic” campaigns. It was inspiring to witness – social media giving rise to a new age of political and social activism.

In 2011, when Occupy Wall Street protests began in New York, organizers turned to Facebook and Twitter to raise awareness of the events and direct people to demonstrations. The hashtag #OccupyWallStreet, aided in the scaling of the protests, turning it into a national series of demonstrations (Tremayne 2013). People have been using social media platforms as a public space since the beginning of the digital age, but it has advanced significantly in the past decade; no longer used solely to provide information about active demonstrations, but as a stand alone protest itself, as we saw on June 2, 2020.

With the rise of social media, we begin to notice the flaws of its imperfect system. For every post demanding change there is an “if you don’t like what I’m doing, unfollow me” post. And that’s what most people did. They unfollowed, blocked, and reported accounts that didn’t align with their beliefs. They created bubbles of their own bias and minimized their opportunities to have meaningful conversations with people that hold conflicting views. In the physical space, the ‘real world,’ this is not the case. You cannot block someone or mute things because you don’t agree with them. That is why we protest: to have these difficult conversations and do something about injustice.

Another issue surrounding digital activism is the violent spread of misinformation. We all have relatives on Facebook that share everything, whether it’s true or not, solely because it aligns with what they want to believe. You swear that if they weren’t family you’d probably unfriend them, or maybe you did. But the truth is, whether fact or fiction, news travels just as fast. While platforms like Instagram and Twitter have fact checkers for information surrounding elections or COVID-19, they can’t catch everything. It falls on individual users to be conscious of what they are sharing and recognize the potential bias of the person behind the original post. Misinformation, however, is not just a result of social media. Since the beginning of human history people have spread rumors and manipulated the truth. Where it was once contained to a more local level, we are seeing social media digitally spread information, real or fake, at a global scale, which leads to hate and bigotry across the physical realm.

When this hate spills out into the ‘real world,’ it is government’s responsibility to regulate the situation. But online, the government has very little control. Accountability lies in the hands of the private companies who own these social media platforms. Every citizen of the United States is granted the freedom of speech and the freedom of assembly under the First Amendment of the Constitution, yet Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, and other social media platforms hold the power to remove accounts that don’t abide by the terms and conditions set forth by the company. The question is: should private companies that operate in digital public spaces have the authority to sensor users?

Public space, by definition, is a democratic space where citizens can interact, share ideas, and discuss issues (Charkrabarti & Gladstone 2017). For centuries, we have only thought about public space as a physical space. In the age of social media and the new ‘digital reality’ created by the Covid-19 pandemic, protests are able to break free of that limited philosophy and engage with a new form of civic space. Our newfound online public space is not without problems. The well-intentioned #BlackoutTuesday protest last year was actually harmful to the Black Lives Matter Movement. Those 28 million posts overwhelmed the Black Lives Matter tag and blocked information about the movement and local protests from circulating.

Digital public space is not perfect. Then again, neither is the physical one. Digital platforms do however make protests more accessible. The two realms compliment each other, by increasing awareness, challenging mental models, and involving more people in the civic process.

Carmona, M., de Magalhães, C., & Hammond, L. (Eds.). (2008). Public space through history. In Public Space: The Management Dimension (pp. 23-42). Routledge. Chakrabarti, V., & Gladstone, B. (2017). Reimagining protest in New York City (and every city). Log, (39), 106-109.

Monckton, Paul. (2020, June 2). This is why millions of people are posting black squares on Instagram. Forbes.

Schwartzstein, P. (2020, June 29). How urban design can make or break a protest. The Smithsonian.

Tremayne, M. (2014). Anatomy of protest in the digital era: A network analysis of Twitter and Occupy Wall Street. Social Movement Studies, 13(1), 110-126.

3

Solidarity can make a new world possible

The world is on fire. And necessarily so fire is cleansing; new things are forged in fire. The oxygen that fuels this fire is not only the killing of unarmed black men but also the dire political outlook of the world. Hope has been squandered by those who have the ascetics of progressive politics but not the actual platform and desire to fight for what is just. This is the scene that set the stage for the fascist theater that was Trump. Politicians and so-called activists who are, as one of my very good friends describes them, “experts in what is not possible”, have occupied the positions of power for far too long.” These actors are a perpetual buffer, separating the mass of oppressed people from much needed progress. The idea that so-called progressive candidates are detrimental to progressive movements is disheartening but unfortunately our reality. We see this in the fact that newly elected President Biden bombed Syria before coming to the aid of the American people whose lives have been ravaged by the Covid-19 pandemic.

But if we have learned anything in the last year it should be that through collective action, we can overcome most things. The progress that has been made in fighting state violence carried out by the police and also our starting a new chapter in our discussion of race and oppression is proof of the inherent power of unity. The calls to defund police, the fight for a living wage for workers, and a reevaluation of the role that the built environment has played in the systematic exclusion and marginalization of communities of color are all the result of collective political action and outrage. The development and expansion of the concept of allyship and solidarity should be viewed as fundamental components of the future we hope to build. This latest phase in the popular movement against the racist, sexist, and xenophobic foundations of American society has completely altered the political landscape in the country–for the time being. And it has caused the nation to take a long hard look at the fundamental racist nature of most of its institutions. However, there are two themes at play here, survival and hope. Those who don’t believe that our society needs a fundamental change and are looking for ways to hijack language and concepts in order to survive to make their modes of oppression more palatable and continue to exploit working class and poor people in this country. On the opposite side are people who believe that a better world is possible, their religion is hope. The keepers of the flame are not dismayed or discouraged by the continued aggression of the enemies of democracy and life nor the glaring absence of their supposed friends at the most crucial of times. Pessimism is not possible because their very lives depend on the issues they fight for. Decent and affordable housing, a living wage and being able to walk the streets without being harassed and murdered are not trivial pursuits, but rather a matter of life and death, literally.

When we take a closer look at history this lesson of unity is ever present. In Newark, New Jersey African-American and Puerto Rican unity was the basis for the political transformation of the city, moving from complete domination by white ethnic groups toward a more representative political landscape. Blacks and Puerto Ricans united to form a mutual defense pact to protect their respective communities from white terrorist violence in the city. The unity of different socio-economic groups in the city’s central ward thwarted racist urban renewal plans when a Yale educated lawyer and a retired occupational therapist organized with low income renters to stop the expansion of the local hospital that would have ravaged the prodomity black neighborhoods of the central ward. When we look at the stories of ordinary people throughout the course of history, we see the need and effectiveness of collective action. Of course I’m biased toward collective political action, I was born and raised in Newark, New jersey. I’m from a place where ordinary people have accomplished extraordinary things. In 1970, 11 years before I was born, Newarkers elected their first African-American Mayor, Kenneth Gibson. A few years earlier, in the summer of 1967, the skies of Newark burned hot orange for five days during the rebellion. In the wake of Newark’s rebellion, in response to apartheid conditions and continued brutal police repression among other injustices, the political landscape was forever changed. There are stories similar to these in all of our cities and towns, buried deeper in some than others. We must understand that the experiences are there waiting to be uncovered while at the same time providing the much needed nutrients of liberation to the soil of possibilities. To understand our collective history of struggle is to better understand what is possible. That’s why it’s so important for progressives and marginalized people to stand up and explain, and fight for the world we would like to see. We know that decent schools are possible because they exist now, just not for all of us. Healthcare for all is within our reach because nations with far less have made it a priority. An anti-sexist and anti-racist world is not a pipedream because if these are not attainable goals, then too many of us cannot exist and be free.

So, in a time when so much is uncertain, we must recognize our memories as the blueprint to a better – more just tomorrow. The time has come to walk towards the sun. The warmth and light of a society truly living by democratic ideals. With so much darkness in the world light is easily identifiable, if we’d only look. If our enemies are talking division let’s speak the language of unity. We must stand shoulder to shoulder determined to gain clarity in this moment of extreme confusion. The confusion that says a living wage for workers is not possible while individual CEO’s rake in a disgusting $2,537 every second of the day. The confusion that is caused by racism that undermines class solidarity while the majority of workers are exploited. If the foundation of the protracted oppression of the poor and working classes is lies, we must build on the truth. We mustn’t lose focus of our mission to build a better world. Because our foes have not abandoned theirs to dominate the world through the perpetual exploitation of the poor and working class. This is the importance of the moment; to clearly define our goals and objectives and identify our power to win. Though the ground is ever moving beneath our feet, our solidarity will provide the stability we need to continue to build a peoples’ democracy – a place where the constant themes will be forged by those who are willing to fight for a living wage, decent housing, and free health care for all. Not those who create scenarios where violence is normal. The violence of slave wages and the constant threat of being evicted. Tomorrow will be framed by the imagination of those who resist state violence against black and trans people, who are willing to fight individuals and institutions that criminalize the poor and see our natural resources and environment as their personal source of capital accumulation. There will be no room for fascism or the anti-people policies of the corporate Democrats who have adopted the progressive language but not the necessary courage the moment requires. We will place one foot in front of the other and continue to march toward the sun, giving birth to a new reality where trauma is abnormal, the perpetual trauma caused by inadequate schools and mounting medical bills. That is what we are fighting for. Our challenges are real, they are not theatrical, so neither can our unity be.

4

Concerning the events of June 2, 2020

The murder of George Floyd at the hands of Minneapolis police officers sparked protests that dominated the summer of 2020. Since then, there has been much written about the injustice of our criminal justice system, the metastasis on city budgets and citizen sanity perpetrated by policing agencies, and the violence that the society we inherited inflicts on people of color and the poor. I hope that this personal narrative, anecdotal in nature, can be a modest compliment to these bodies of work.

As a frequent attendee of the New York City protests this past summer, I hoped to document my experience for personal posterity as 2020 drew to a close. My submission to Urban Magazine was the impetus I needed to finally put pen to paper. The following documents a vignette of a night less than a week after the unrest began. I do not believe that this discourse is zero sum, that the presence of my voice in this magazine drowns out that of countless, more deserving others. That being said, it is understandable if the reader is not interested in reading a white man’s perspective. I write using the only perspective I have.

Around 6 pm on the evening of Tuesday, June 2, I left my apartment and headed to a protest that was taking place on the Upper East Side at Gracie Mansion. Finding the East River Path blocked, I deviated to city streets, in search of a group of protestors in Midtown. Around 7 pm, I joined a group marching along Park Ave, my tongue tepidly shaping the names of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor in chants that would become ubiquitous as the summer went on. By 8 pm, the sun was beginning to set and I split from the group when we got to Union Square. Just as the Mayor’s curfew was coming into effect, I ran into a smaller group nearby that was in a confrontation with police. The protestors stood their ground and eventually the police retreated to their vehicles and drove away, to much celebration. One protestor carried an upside down American flag. Another, brandishing a lighter, asked if he could burn it.

Just as the police left the scene a large group made its way to Union Square, merging with the smaller one I was a part of. This group had several leaders, who I only classify as such because they carried bullhorns, although I would soon learn that to the extent the early protests were organized at all it was ad hoc and these leaders were self-appointed. The self-proclaimed leaders disagreed on which way to take the large crowd and encouraged us to take a knee while a decision was made. During this lull in the noise, the sound of glass shattering split the air. The consternation about looters had already begun in the media, but this was the first time I encountered them. The men with bullhorns lambasted the looters and quickly realized their error in stopping the march. The looters didn’t seem to care. We marched south as dusk settled in.

My memory of the events starts to get a bit hazy after nightfall. I’ll admit that I am a terrible estimator of headcount, but if I were to guess, it felt like there were over a thousand of us in our group, which stretched back in an immeasurable tail. I remember being in the West Village and then Soho. Turning left onto Canal Street in Tribeca. The ad hoc organizing became increasingly more organized - particularly among the minority of cyclists in the pack. As cyclists, we played a unique role, scouting ahead for police presence, directing foot traffic with flashlights when the group would turn, and blocking cross traffic, although we encountered few drivers after the curfew. I remember when a cyclist from another protest rode up and told the de facto leaders of our group that their group was heading for the World Trade Center. I accompanied him back to his group to try and arrange a merger between us. Riding between the two crowds took us through a surreal, empty, and starkly quiet city. In some places, we weaved among makeshift barricades of trash that protestors had erected in the wake of their march. Going from the clamor of the crowd to the empty canyons of Soho, its storefronts hardened with plywood, was disorienting.

I remember looters breaking the window of a liquor store in Tribeca. The typical cyclist response to this eventuality was to put our bikes in front of the broken storefront and chant, “keep moving!”, until the crowd had passed, but there was little we could do. The looters were just teenagers and they seemed to be doing it for kicks. As the night went on and protestors trickled into the subway system, the looters seemed to stick around and the proportion of looters to protestors grew. The police became more aggressive too – staying in their vehicles and keeping their distance but occasionally rolling up on the march with lights on in a column. Around midnight, the group was marching around City Hall Park when I noticed a small contingent of protesters leaving down a side street. I recognized one of them as the bullhorntoting protestors who gave me good vibes. I felt like it was time to go, so I followed them. We got to talking and introductions when suddenly a column of police vehicles streamed around a corner. Half of us got away but the rest of us got caught standing stupidly on the sidewalk. When the police officers confronted us, we weren’t read our Miranda rights. My bike was taken away from me. While being zip tied, a white shirt (shorthand for a senior or commanding officer) congratulated the officers on their “nice work.” This was confusing. Hadn’t they let half of us escape and only apprehended those of us that didn’t run? The seven or eight arrestees were lined up and patted down. None of us were violent. One man who was with us must have been 7’ tall and I could tell the police were afraid he would try to resist, but he didn’t. One officer asked what was in my backpack. Before I could answer, he dumped it upside down onto the pavement, shattering my phone screen. Its other contents were a light jacket and a water bottle, which was untouched for most of the night. I was already thirsty.

We lined up to board the paddywagon. On the way in, an officer relished the opportunity to tighten each of our restraints, sharpening the pain in my wrists. Once in motion, we continued introducing ourselves in an attempt to make light of the shitty situation. We were taken to a booking facility on Schermerhorn Street in Brooklyn (the Manhattan booking facility was apparently full) and found ourselves in a line stretching out the door and around an enclosed but open-air parking area. It must have been past midnight when we arrived and having spent the previous 5 hours riding my bike, the next few hours of standing elongated before me. The dehydration and pain in my wrists started to overwhelm me as time passed. Afraid I would faint, I crouched against the bricks, unable to break my fall with anything else. I remember another protester I’d been arrested with, a nonbinary person who I’d later learn studied landscape architecture, kissing my shoulder in comfort. My vision was cloudy. We asked for water many times, and were told there was none. I thought of the full water bottle in my backpack.

As the line progressed and got longer behind us, we realized we had been treated comparatively well. Protestors arrived with swollen eyes, covered in bruises. It was easy to recognize how the white prisoners were being treated with less violence and more sympathy than the others. Of the arrestees in this staging area, about half had light skin. We kept asking for water and eventually our arresting officer, P.O. Rueda, allowed us to sip from the water bottle from my bag. At the same time, a Black protester my age was vociferously asking for the same of his officer: “We see guys like this all the time,” Rueda explained in undertone. “They just do this for the attention. Give him water, and the next thing you know, he’ll be asking for food. It never stops.”

After a few hours we made it inside the building. Our restraints were removed (the relief!) and we were put into holding cells divided by male and female gender identities. It goes without saying that there was not adequate room for social distancing but I had already concluded that I’d be infected with COVID-19 by the end of the night, and felt no trepidation on the subject. We were searched again. The drawstrings on my pants were cut and my shoelaces removed. I learned Rueda was Colombian and that he had a graduate degree. He referred to the week’s events as “the Purge.”

The rest of the night amounted to waiting in line, being put in a cell, waiting in line, and then being put in another cell. The police called us “bodies” or “collars.” Their badge numbers were obscured by the Thin Blue Line (a motif used by police officers to show their distinctness from the communities they serve. During the protests they would obscure their badge numbers ostensibly to pay homage to officers that died of COVID-19, but the practice had the effect of limiting officer accountability by preventing their identification by badge number). Mask use was infrequent. The hallways were narrow and stained, and a riot helmet and club bounced at the hip of each officer. To open a cell at the end of the long hallway where we queued an officer would have to shout down the line for someone at the front desk to unlock it. This happened constantly. Out of sight, a man had his own cell. He was talking to himself, screaming, rattling the bars of his cage. It was difficult to hear anything else.

Despite the noise, I tried to sleep in the final cell of the night, this one with benches lining the walls. I knew the subway was closed, as were the Brooklyn, Manhattan and Williamsburg bridges. I prepared myself for the long walk to West Harlem. Finally, Rueda arrived to let me out. We had developed a custom of clapping and cheering when one of us was let out and my release was not an exception. At the exit, I was given my summons and my backpack. I walked out alongside my new friend (they had been placed in the female-identifying cell despite their gender ID) who was released at the same time. A smartly dressed detective with a friendly demeanor stopped us and asked us some questions about who organized the protest. She seemed to be trying to figure out if we were “antifa.” We told her we didn’t know and trudged to the sidewalk.

Around the corner we found a group of people with water bottles, snacks, and phone chargers. Jail support. They gave us a ride home.

5

Evolution of City-Organism: Fight or Flight?

I stood in shock amongst my friends on the middle school football ground on January 26, 2001, when a 7.7 magnitude earthquake, lasting over 2 minutes, destroyed many settlements and killed over 30,000 people in the Western State, Gujarat, India. Ten years later, in 2011, I researched the transformation of the city, Bhuj, India at the epicenter of the quake.

We build to endure, to resist time, although we know that ultimately time will win. What previous generations erected for eternity, we demolish. Then, with similar intent, we lay stone upon stone and build again. Permanence is instinctively sought. The built environment, like all complex phenomena, artificial and natural, endures by transforming its parts.

–Habraken, N.J, Structure of the Ordinary

Many beautiful dwellings, streets, monuments, and lives withered, but they picked up the pieces, adapted to the situation, and prepared themselves and their built environment to endure a future calamity. Like Bhuj, many cities are redesigned after a disaster. Consequently, we redesign how we relate culturally, socially, and even politically to the city after re-organizing it to mitigate future perilous events. The urban human finds themselves constantly updating and generating newer versions of themselves, and therefore we see a rapidly evolving society.

We are not strange to these rapid changes in our social interactions owing to the current pandemic. A protein molecule permeated our biological pathways that resulted in reshaping our cultural practices of assembly and congregation, perhaps for many years to come. After almost a year of holding onto the hope that we can go back to our previous state, it is time to see this as an opportunity for urban systems to not merely create possibilities to physically distance and provide sanitary conditions, but facilitate an egalitarian society that can have a chance to thrive under any future adversities.

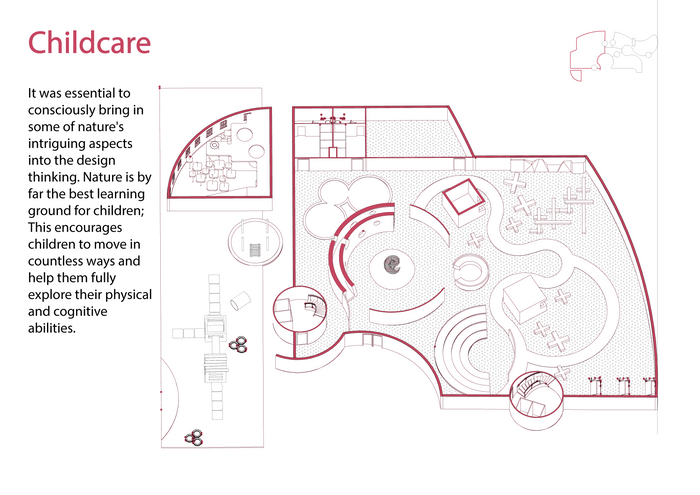

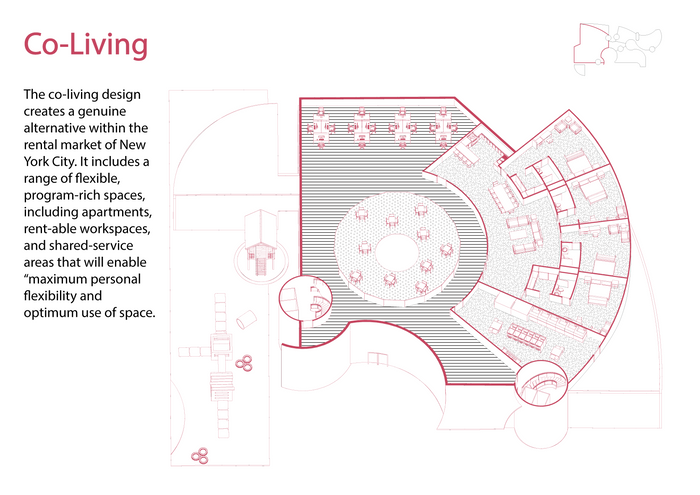

The pandemic brought forth imparities of our society that have been ignored and, therefore, most affected as the economic landscape changed drastically in a matter of days in March 2020. With ‘shelter-in-place,’ the onus of reproductive work (Federici 2012) was thrust on women across all cultures. In the last year, 2.3 million women in the US dropped out of the workforce, often to perform child care, when schools and daycares closed. (Jordan 2021) Within this new ecosystem, a “racial justice paradox” has emerged: Blacks and Latinxs are more likely to be unemployed due to the impacts of the pandemic on the labor market, but they are also overrepresented among essential workers who must stay in their jobs, particularly lower-skilled positions, where they are at greater risk of exposure to the virus (Powell 2020).

Domestic work in Indian urban homes is typically performed by migrants from remote villages that were suddenly left without jobs or support from the administration. Amidst a complete lockdown, unable to commute, helpless and jobless, many chose to return to their villages on foot. There hasn’t been a time when it was more evident that a city’s infrastructure is measured by the equity of privileges and opportunities rendered to its people. What kind of evolutionary changes within the infrastructural zone will help us prevail under these conditions?

In most living organisms, a fight or flight response to stress stimuli causes a reaction within the nervous system triggered in the amygdala secreting adrenaline. The activation of the pituitary gland causes a hormone release that triggers further reactions to boost energy in the organism to prepare for physical action against imminent danger. From an evolutionary perspective, quick physical response to threatening stimuli provided early organisms with biological mechanisms to rapidly respond to threats and thrive under perilous conditions. Some organisms can also maintain homeostasis even under such conditions. (Canon 1915) The fascinating protocols of organism design offer possibilities for an investigation into a city-organism.

Like organisms, cities are an assembly of functioning parts with protocols that describe their disposition. An arborescent metaphor for a city-organism signifies authoritarian yet accretive growth of the settlement. In contrast, Fritz Lang’s “Metropolis” depicts the city as a machine powered by workers’ servitude while the overlords enjoy the expensive skyscrapers. In both cases, the metaphors of an efficient machine and an ever-expanding organism, authoritarian politics and its control over the socio-cultural environment are evident. The growth and efficiencies are controlled by a power regime to toy with the societal imparities, limiting opportunities for some while awarding privileges to a few in exchange for more power. Theocracy ordered the early medieval cities, where the central position belonged to the monarch and subsequent hierarchies were organized based on occupational specialties. Cities past the industrial era remain reminiscent of this disposition based on the socio-economy of its citizens.

Technology plays a critical role in taking control of these protocols and breaking away from the city’s authoritarian structuring. Over the past 30 years, it progressively created a socio-technological environment in which a human exists as an Avatar (a representation) of themselves in media, unbound by their contextual conditions. The socio-technological environment offers its occupants a level playing field, possibly pre-empting devolution of the authoritarian politics that exacerbated the acute economic imparities during the pandemic.

Under the threat of the contagious virus, our collective fight or flight response kicked in, and we locked ourselves out from the thrills of urbanity. We disabled our most tactile and present forms of communication and found media prosthetics to compensate and expand our potential under these circumstances. We accepted a life within the socio-technological environment. Platforms like Zoom, Microsoft Teams, and Google Meet could connect people online, recreating the infrastructure zone that facilitated their physical congregation pre-pandemic. Taking a step further, Gather.town transformed the media to emulate spatial conditions of meetings such as office environments, living rooms, schools, game rooms, speakeasy, waterfronts, and so on. Creating this media environment bore no relationship to the city or context. Instead, traveling across the globe and subverting placeness, it defined a techno-spatial endeavor that may be our most prominent evolutionary feature under these circumstances.

Communication technologies have come to the rescue of the human network in the past. In March 2011, Japan was hit by an 8.9 magnitude earthquake that initiated a 30-foot high tsunami. The giant wave then triggered a nuclear meltdown of the Fukushima Daichi plant, killing 1800 people and completely demolishing Japan’s telecommunication systems. This distressing experience prompted employees of NHN Japan, a subsidiary of a South Korean internet company, to devise a solution for people to contact family and friends during crises. Line was launched as a messenger service for instant communication where users can text and call people from their smartphones that rely on Internet-based resources to connect (Bushey 2014). Not long ago, a group of coders built a free online tool to create child care co-ops such as Komae. “On Komae, parents swap ‘Komae Points’ with other families as a way to manage and coordinate care for their children within a trusted network. I sit for you. You sit for me. We don’t pay for sitters anymore—Huzzah!” as advertised on their website. Mutual aid networks have flourished during the pandemic. A group of people seeking services and help use something as simple as a Google Doc, where they write down what they need and provide in exchange, forming a network of symbiotic relationships. Such initiatives in response to calamities did not rely on the primary infrastructure of their cities. Communities banded together to pool and increase their resources, creating a participatory infrastructure based in a socio-technological zone.

Like a network of biological protocols inherent in the organism’s design, which kick-starts a series of reactions in the neural pathways, the human network switched from a socio-cultural environment to a socio-technological environment as our physical interactions were prohibited during the pandemic. Subverting the geographical limitations, connecting across the continents, and creating an infrastructural zone independent from boundaries of authoritarian ideologies and motivations, the evolved human inches close to dissolving the accumulation of power. This is an evolutionary response of the human network under a bio-spatial threat. Can cities create such socio-technological infrastructures that host a participatory network providing equity of opportunity across communities?

Stepping back from morphological transformations to create adaptability within our environments, we must focus on designing protocols that establish relationships and define the actions performed within the socio-technological zone resulting in an ephemeral infrastructure. This infrastructure will be inherently adaptable, just like an organism.

Colomina, Beatriz, Wigley, Mark, (2016) Are We Human?, Lars Muller Publishers, Zurich

Federici, Silvia, (2012) Revolution at point zero: housework, reproduction, and feminist struggle, Oakland, CA: PM Press; Brooklyn, NY: Common Notions: Autonomedia

*Federici uses this term not simply to refer to having children and raising them; it indicates all the work performed to sustain ourselves and others around us.

Kisner, Jordan (2021, February 17). The Future of Work, The Lockdown Showed How the Economy Exploits Women. She Already Knew. New York Times. Retrieved on February 22, 2021 from https://www.nytimes.com/2021/02/17/magazine/waged-housework.html?action=click&block=moreinrecirc&impression_id=eaeec756-7551-11eb-9838-37ecdfcbe4da&index=4&pgtype=Article®ion=footer

Powell, Catherine, (June 4, 2020). The Color and Gender of COVID: Essential Workers, Not Disposable People, Think Global Health Retrieved on February 22, 2021, from https://www.thinkglobalhealth.org/article/color-and-gender-covid-essential-workers-not-disposable-people

Cannon, Walter Bradford(1915). Bodily changes in pain, hunger, fear, and rage. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts. p. 211.

Bushey, Ryan, (Jan 12, 2014) How Japan’s Most Popular Messaging App Emerged From The 2011 Earthquake, Business Insider

6

Prohibition and Appropriation:

Spatial Activism During the Coronavirus Pandemic

In fighting this regional, and now global COVID-19 pandemic, governments have deployed both voluntary and involuntary forms of quarantine as an essential measure to contain the spread of the disease. This piece explores how emergent medical restrictions, i.e. quarantine and social distancing, powered over regular social order, restricted daily public spaces, and affected the spread of the disease. Furthermore, this piece discusses how people in quarantine employed different spatial activism strategies to appropriate, create, and reproduce new public spaces.

Pandemic, Quarantine, and the Exercise of Power

The word “quarantine” evolved from the

Italian phrase “quaranta giorni,” which

means the time of forty days. These

forty days of isolation originated from

an ancient Venetian policy enacted in

1377 to segregate ships from plagued

areas to ensure there were no cases

on board (Online Etymology Dictionary,

2011). During the COVID-19 pandemic,

quarantine means retreating physical

movement from public spaces to one’s

home or hotel room. Historical lessons

from contagious pandemics like the 1910

Manchurian plague and 1918 Influenza

pandemic, and current examples of East Asian countries’

response to COVID-19 all proved the effectiveness of

quarantine as a public health tool. Research also showed

strict transmission control measures, like shutting down

public transportation, entertainment venues, and

gathering, will effectively mitigate the spread of the virus

(Kraemer et al., 2020; Tian et al., 2020).

However, exercising power during quarantine can also be discussed through Michel Foucault’s (1977, 1978) medical knowledge arguments. Focault argues the heart of modernity in European discourse relies on the idea that subjects marked as abnormal, diseased, criminal, or illicit should be isolated for their betterment and the collective good. Subjects who resist the logic of these disciplining institutions, who fight their confinement or resist enclosure and separation, simply reinforce the perception that they are dangerous, amoral actors who need and deserve segregation. Foucault (1984) further analyzed the noso-politics[biopolitics] under the topic of medical knowledge as power. He concludes that medical service once exercised surveillance functions identifying “unstable” or “troublesome” elements in the society.

Moreover, in the eighteenth century, the exercise of power furthered the disposition of order, enrichment and health, through various regulations and institutions in the name of policing. Giorgio Agamben (2020c) argued the COVID-19 pandemic turns the state of exception into a normal condition of our society, and worried this sacrifice of freedom for security reasons would erode citizens’ social relationships, work, and even affections. Eventually, Agamben argues, this state of exception would turn every one to bare life (la vita nuda). Agamben (2020a) notes the state of emergency might pose a threat to society by promoting unnecessary fear between citizens, and turn everyone into a potential source of infection, like the “untore[plague-spreader]” in the 1630s Great Plague of Milan under Manzoni’s pen (Agamben, 2020b). Fan (2003) also mentions the pronounced social impact of the 2003 SARS outbreak could be attributed to “the almost costless and rapid transmission of information due to the development of modern media and communication technologies.”

Example of Space (Re)production - Spatial Activism by Skateboarders

The COVID-19 lockdown kept citizens from their usual

public space - sidewalks, streets, and plazas. Where can

we find new public space during the state of exception?

Maybe we can learn some lessons about spatial activism

from skateboarders. Borden (2001) describes the three

steps of spatial activism used by skateboarders to create

territories in his enlightening book Skateboarding, Space

and the City: Architecture and the Body. Skateboarders

first find neglected space in the suburbia city; second,

skateboarders showcase their die-hard skateboarding

tricks to coin the occupation, and; third, spread the idea of

skateboarding space to the larger public by documenting

the activities with photography and movie clips. Through

these three steps, skateboarding transforms the material

realm of American suburbia into a romantic sphere of

destabilized movements.

The following sections review how citizens around the world protect their public spaces through spatial activism during this state of exception brought by the COVID-19 pandemic.

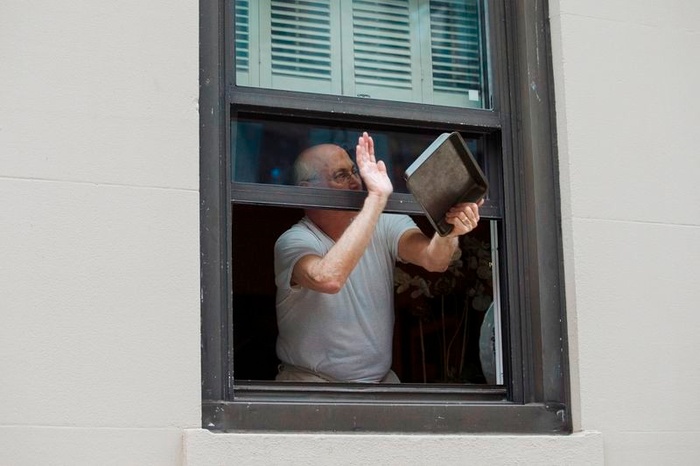

Find and Utilize the Balcony as Public Space

Exercising social activities on balconies marks the

declaration of visibility and the reclamation of public

space by citizens (Caledria, 2012). Facing the street

and plaza, the balcony is spatially proximate to former

public spaces. Balconies are also regarded as the space

between private and public, as activities on the balcony

will be judged by others, despite them being performed

on a private property. By exercising activities like singing,

cheering, and shouting, the balcony serves as a public

space in times of quarantine.

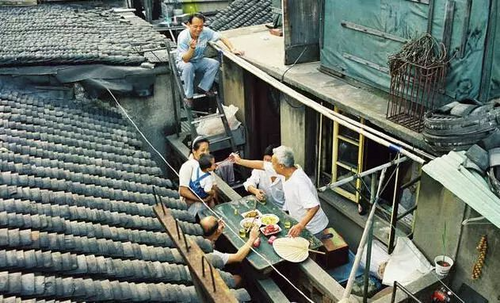

Balcony in western modern architecture has its root from the Greek vernacular housing’s outside room, in the form of a terrace, flat roof, or solarium (Campbell, 2005). Modern European architecture in the 1900s adopted the balcony or open window as a means to treat tuberculosis. However, in modern times, balconies in metropolitan cities usually function as relaxational and recreational spaces. When the COVID-19 pandemic makes the government opt to close parks and trails, the balconies in highly-dense cities rebuild the connection between homes and households. A YouTube video shows that Wuhan residents in a gated community walk to their balconies, first chanting “Keep it up, Wuhan,” followed by singing the Chinese national anthem together (Run Runner, 2020). During the spring and summer of 2020, every day at 7 pm, New York City residents went to their balconies to clap, applaud, bang pots and pans, and play instruments to convey gratitude to frontline medical workers. People in Naples, Italy, hung “solidarity baskets” filled with food from their balconies to help feed the homeless on the street amidst the social distancing orders (Poggioli, 2020). By intensifying the activities on balconies from relaxation to socializing, the citizens appropriated and gave new use to them.

Source: (Mordant, 2020).

Besides the functions of gathering and performing daily life, public spaces in the city have often been valorized as democratic spaces of congregating and political participation, where groups can vocalize their rights. A form of spatial activism appeared when the residents used balconies as a channel of democracy. Since January 23, residents in Wuhan were not allowed to leave their apartment for 45 days. During that period, all groceries and daily needs were delivered to the door by either the neighborhood committee or property management companies. Some residents were not happy that the property management company de facto monopolized the food market and charged high prices and delivered bad produce. On March 8, 2020, when an inspection team led by Sun Chunlan, Vice Premier of China and chief of China Coronavirus Task Force, arrived at a neighborhood in Wuhan, residents shouted “all of this is fake” from their balconies to Sun and other government officials expressing their anger (Guardian News, 2020). Through turning balconies into democratic spaces, the residents vocalized their rights to the public and government.

Social Media as New Public Space

Social media platforms make the world

more connected during quarantine.

People post videos and send messages

on social media, which is more direct

and comprehensive than traditional

print media. During the pandemic,

Internet traffic in China increased by

50% compared to the end of 2019 (Liu,

2020). Flourishing social media, to some

degree, compensated for the loss of

public space. Social media helped some

cities or groups of people gain more

attention under the disease. Webster

(2011) argued that digital technology

provides an unlimited supply of media,

but people only have limited public

attention. During the early stage of the

pandemic, unable to spread the dire

need on social media means being

abandoned by crowdsourcing help,

one of the primary channels of personal

protective equipment (PPE) supply.

Community advocates start fundraising

campaigns on social media for money

and resources to secure PPE for the

hospital, while architects and makers

exchanged knowledge on 3D-printing

face shields to deal with the local

shortage of PPE.

However, social media also has many downsides. While we saw much information about the hardship in United States, Italy, Spain, and the UK on the western-centric English social media and news platform, people suffering the disease in Turkey (#9 total cases) and Iran (#10 total cases) in April, 2020 were barely visible in the English-speaking social media world. The absence of nonwestern stories on international news and social media is critically dangerous when the amount of attention you gain could be directly related to the aid you will receive.

Space after the COVID-19 pandemic

In the foreseeable future, our society will

still be functioning in a state of exception.

The pandemic revealed the extent of our

public spaces’ vulnerability. Government

and social advocates, even the general

public themselves must find ways to

demilitarize our public space and return

the physical and virtual public space

to the public. Jacques Ranciere (2020)

mentioned that neither politicians,

who rely on a “state of exception,” nor

intellectuals, who want to overthrow the

current society, but only those working

for the present can change the process

in the future.

Agamben, G. (2020). The state of exception provoked by an unmotivated emergency (Trans.). PositionsPolitics: Praxis. http://positionswebsite.org/giorgio-agamben-the-state-of-exception-provoked-by-an-unmotivated-emergency/

Agamben, G. (2020). Contagio. https://www.quodlibet.it/giorgio-agamben-contagio

Agamben, G. (2020). Chiarimenti. https://www.quodlibet.it/giorgio-agamben-chiarimenti

Baltimore, D. (2003). SAMS – Severe Acute Media Syndrome? Wall Street Journal, 2003, April 28.

Borden, I. (2001). Skateboarding, space and the city: Architecture and body. Oxford: Berg.

Caldeira, T. P. (2012). Imprinting and moving around: New visibilities and configurations of public space in São Paulo. Public Culture, 24(2 (67)), 385-419.

Campbell, M. (2005). What tuberculosis did for modernism: the influence of a curative environment on modernist design and architecture. Medical history, 49(4), 463-488.

Fan, E., X. (2003). SARS: Economic Impacts and Implications. Asian Development Bank. https://www.adb.org/publications/sars-economic-impacts-and-implications

Foucault, M. (1984). The Foucault reader (P. Rabinow, Ed.). New York: Pantheon Books: 276-277

Foucault, M. (1978). About the concept of the “dangerous individual” in 19th-century legal psychiatry (A. Baudot & J. Couchman, Trans.). International journal of law and psychiatry, 1(1), 1-18.

Foucault, M. (1995 [1977]). Panopticism. In Discipline and Punish. The Birth of the Prison (A. Sheridan, Trans). New York: Vintage.

Kraemer, M. U., Yang, C. H., Gutierrez, B., Wu, C. H., Klein, B., Pigott, D. M., … & Scarpino, S. V. (2020). The effect of human mobility and control measures on the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Science, 368(6490), 493-497.

Lefebvre, H. (1991). The production of space. Oxford: Blackwell.

Liu, Y. (2020, April 24). [During the epidemic, Internet traffic increased by 50% from the end of last year]. Science and Technology Daily, 4. (in Chinese)

Mordant, A. (2020). Tony Manning uses a frying pan to make noise from his window Tuesday night [Online image]. New York Daily News. https://www.nydailynews.com/coronavirus/ny-coronavirus-apartment-applause-20200401-krgylnadfferrgqqp5tlm6vnay-story.html

Poggioli, S. (2020). In Naples, Pandemic ‘Solidarity Baskets’ Help Feed The Homeless. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2020/04/07/828021259/in-naples-pandemic-solidarity-baskets-help-feed-the-homeless

quarantine (n.). (2011). In Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved March 30, 2020, from https://www.etymonline.com/word/quarantine

Rancière, J. (2020). [Viralità / Immunità. due domande per interrogare la crisi: #2 | JACQUES RANCIÈRE / ANDREA INZERILLO]. Institut français Italia. https://www.institutfrancais.it/italia/viralita-immunita (in Italian)

Rose, N. (1999). Powers of freedom: Reframing political thought. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Run Runner. (2020). Coronavirus - People singing the Chinese national anthem. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cdvBkyNbhfs

Tian, H., Liu, Y., Li, Y., Wu, C. H., Chen, B., Kraemer, M. U., … & Dye, C. (2020). An investigation of transmission control measures during the first 50 days of the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Science, 368(6491), 638-642.

Webster, J. G. (2011). The duality of media: A structurational theory of public attention. Communication Theory, 21(1), 43-66.

7

Casa de Todos (Home for all):

The day when the arrival of

COVID-19 in Perú brought along a new chapter of hope

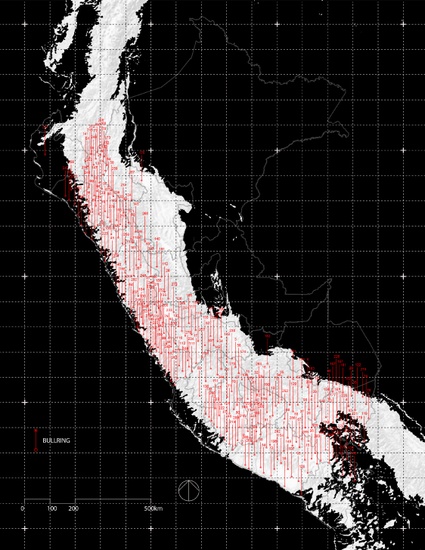

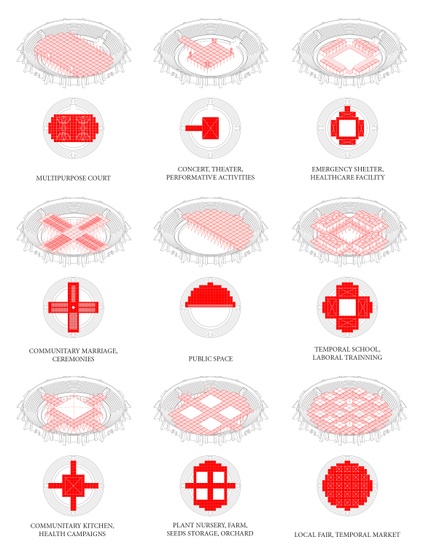

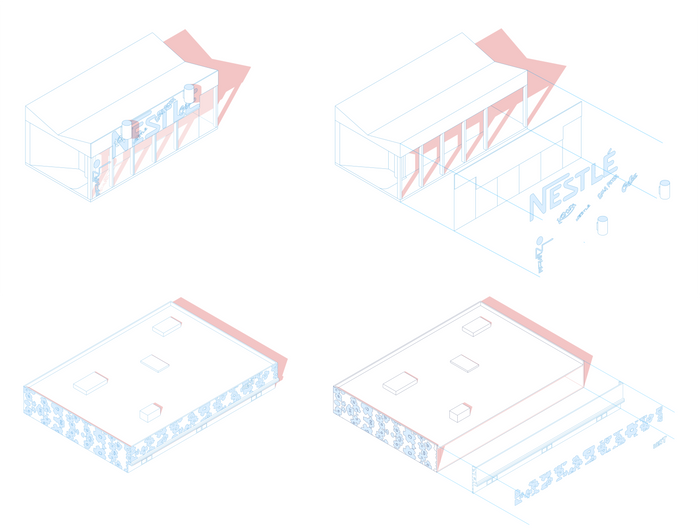

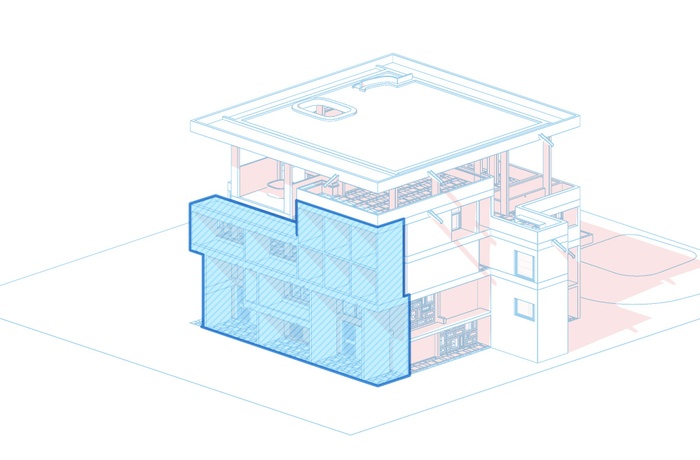

On March 31st, 2020, a few days after the Peruvian Government had imposed a strict period of confinement, a temporary structure for homeless shelter Casa de Todos (Home for all) was installed in the arena of the oldest bullring in the Americas, Plaza de Acho. The day that COVID-19 arrived, not only marked the beginning of a nationwide emergency, but also represented the disruption of a century-long systemic patriarchal norm that uses violence for spectacle.

Casa de Todos is a private-public initiative proposed by Lima´s Governor, Jorge Muñoz, and the Society of Charity of Lima, which sought to bring more than one hundred homeless people into a safe space where they could receive medical care and food. Most importantly, Casa de Todos served as a temporary shelter. The central arena was covered by a membrane floor and organized in 5 modular structures: a central structure, divided into bedroom units, and 4 smaller modules for services and medical assistance.

Since its construction in 1766 in the Historic Center of Lima, Plaza de Acho has witnessed a number of unusual events, such as the rise of the first hot-air balloon in South America in 1840, political rallies, concerts and different sport tournaments. Nevertheless, it was the first time in its 254-year history that Plaza de Acho was utilized for a purpose other than leisure activities or spectaclerelated events. In fact, it was the first time in 74 years that the biggest bullfighting festivity in Peru, El Señor de Los Milagros (Christ of the Miracles), was canceled since it started in 1946. Certainly, the COVID-19 pandemic made a humanitarian effort possible, an attempt that different social and political groups had sought for many years.

Even though this humanitarian effort was celebrated by the majority, it was still expectedly condemned by some people. Nevertheless, a space for exclusion purposely conceived for activities perpetuating non-human violence has now been transformed into a space for healing and refuge. Certainly, the decision on choosing Plaza de Acho for a medical emergency event is way beyond its capabilities for accommodation: the bullring not only offers a secluded empty space, but also comes with technical installations and basic services, such as electricity, sewage, and water.

inception of Casa de Todos reinvigorated a fervent debate on whether the eventual prohibition of such a sanguinary practice must necessarily be followed by the inherent demolition of these buildings. The abolition of bullfighting not only requires social and political efforts but also architectural responses. Casa de Todos raised a desire to reveal possible modes of occupation and to explore new ways to re-signify nearly 300 existing bullrings dispersed throughout the Peruvian territory, most of which are located in underserved communities in the Andes mountain range.

Architects and urban thinkers have a responsibility to question the underlying essence of infrastructure within the built environment, critiquing its implications of oppression, emanating from a period of European dominance, and its systemic dimensions. In less than 6 months, ahead of the bicentenary of the Peruvian Independence, it is important to question whether existing infrastructures, such as Casa de Todos, represent an opportunity to intervene in the inherited territory in a responsible and sustainable manner, avoiding the repetition of past mistakes perpetuated by former colonizing powers, to work from a logic of tabula rasa.

This speculative exercise is part of an ongoing research that aims to unveil the spatial and polyfunctional possibilities of third category bullrings in Peru, through the design of a flexible and temporary structure. The project seeks to enhance different modes of interactions and occupations, allowing to inhabit these infrastructures in a short time period, in an economical and sustainable manner. The elaboration of a manual of instructions will allow its systematic production and implementation, making possible its replicability throughout the Peruvian territory.

Baez Gonzalez, J. (2021, February 05). Casa de todos, el proyecto en Perú que transformó una Plaza de toros en albergue durante la pandemia. Retrieved February 12, 2021, from https://www.aa.com.tr/es/mundo/casa-de-todos-el-proyecto-en-per%C3%BA-que-transform%C3%B3-una-plaza-de-toros-en-albergue-durante-la-pandemia-/2134520

Beneficencia de Lima. (2020). Retrieved February 12, 2021, from https://beneficenciadelima.org/public/casadetodos/

Cáceres Alvarez, L., Fuller, C., Krajnik, F., & Vidal, J. (2020). Casa de Todos. Rostros de la calle en Plaza de Acho. Lima: Universidad Peruana de Ciencias Aplicadas (UPC). Available at https://repositorioacademico.upc.edu.pe/handle/10757/653738

8

Advocating for Public Space in a Pandemic

Not many would know that Eastern Queens is home to beautiful parks rich with natural resources. While the parks are geographically close to each other, they are physically isolated and many existing pathways are disconnected. While a few plans to connect these parks were drawn in the 1970s and 1980s, neither were fully implemented.

Upon conducting research and community outreach, the value of this network of parks to the surrounding communities became evident. Residents use them for sports, leisure and family time, and essential day-to-day activities. However, massive highways and infrastructure systems built in the 1970s resulted in multiple gaps and barriers between the parks. They not only altered the physicality of the space, but also left inconsistencies in a landscape that was meant to be for people and ecology to flourish in the city. Many inaccessible and accident prone zones have immediately excluded parts of the community – mostly the elderly, children and disabled.

For the last few years, caring members of the community have been advocating to address these inconsistencies and create a continuous, protected and accessible trail that serves walkers, joggers and cyclists along the historically-proposed greenway. The proposed pedestrian routes and bike lanes would encourage sustainable modes of transportation and walkability, significantly improving public health. At a time when access to open public space is especially important, it is crucial to think about its quality and long term feasibility.

Our process began when concerned community representatives sought to expand their advocacy efforts. The cancellation of their annual event, Tour de Flushing, in July 2020, instigated the rethinking of their advocacy methods. Prior to the pandemic, the event raised awareness and garnered incredible support for the Eastern Queens Greenway (EQGW). We collaborated with local activists and Transportation Alternatives (a non profit organization) to design and visualize a cognitive map, supporting their vision. Sagi Golan, Senior Lead Urban Designer at NYCDCP and our Summer Studio faculty from GSAPP, mentored us.

The project’s potential to implement a bottom-up approach to urban design was especially exciting. Additionally, we saw it as an opportunity to inspire the residents around the area and the entire city to recognize the Greenway network’s capacity to benefit the economy of surrounding neighborhoods, promote inclusion and equal opportunities, and, thereby, enhance the livelihood of future generations, specifically in Queens, which houses one of the most ethnically diverse and underserved population in the city.

Framework and Site Visit

After our initial meeting with community members, we identified our main goal: creating a virtually accessible tool, with a tangible product, that can be easily used by the residents. This tool could potentially aid future advocacy and speak to safety and accessibility in their neighborhoods. A compelling visual map would be a useful output to reach out to the communities around the greenway as well as key stakeholders.

Next, we visited the site accompanied by two community members familiar with the trail and its history. With complete safety measures and physical distancing, we experienced the fragmentation and discontinuity caused by the highways bisecting the parks, while also observing the rich ecology and transformative landscapes along the route. Interacting with the community members allowed us to see the greenway through their eyes and to share their vision. This experience set the tone for the virtual collaborative work going forward.

Process and Collaboration

We arranged bi-weekly meetings with the community and Transportation Alternatives. We also conducted virtual meetings with neighborhood residents, to better understand their perspective and interactions with the EQGW. Upon publishing the first version of our work, we were contacted by a HUD politicians team to brainstorm planning policies for the coming term that would enable greenways like the EQGW to come to life. All of these meetings aided our holistic understanding of the realities of the EQGW, particularly its undeveloped potential.

Presenting the EQGW

The map was created to increase awareness, accessibility and orientation around the EQGW; outlining the experiential route of the greenway, highlighting hidden gems and attractions, and revealing the diverse ecologies existing along the trail. The trail is divided into segments to demonstrate time based on different means of movement: cycling, walking and running. The map introduces historical anecdotes, wayfinding guidelines, and amenities. It contains 4 main layers—Highlights, Activities, History and Ecology—referring to different components throughout the trail. We used a pamphlet and a story map to support the community advocacy effort. The pamphlet, a folded letter format, is used as a guiding map to explore the trail, and its hidden magical spots while marking the dangerous intersections in real time. As a complementary tool, the storymap gives the community and other visitors context of the trail history, recommends sites to visit and offers videos from existing cycling paths. Both tools provide information for new visitors while, at the same time, improving accessibility for current users and local communities.

Conclusion and Future Vision

The pandemic highlighted the vitality of open public spaces in the city. It pushed to advocate for their existence and their quality — sustaining themselves and creating space that are contiguous and pleasurable for all. We should be rethinking how we use open space to improve community life, environmental sustainability, and improved health and quality of life. In the same way that past afflictions were a catalyst for improved infrastructure, we must similarly reform open space to make it a viable infrastructure. This concept may sound basic to an urban designer or an architect, but it has been proven to us that public open space is integral to the community as well, and residents are willing to participate actively in order to move forward.

As designers, we began envisioning what the greenway could be and were fortunate to be able to explore our skills for a worthy cause. Spatial analysis and mapping tools were successful in engaging with the locals in a straightforward manner that resonated with them and their aspirations. This collaboration has taught us that small steps and gradual processes can be the seed for immense change – one that is more contextual, grounded, and achieved only over time. As we wait for this big change to come, we can enjoy what the Greenway has to offer and hope that more people will come together to make a change, and imagine what the EQGW can become, together.

9

International Travelling in Times of the Pandemic: Worth the Retelling?

After taking the longest nonstop commercial flight for 19 hours, I landed in JFK airport on January 23, 2021. I passed through the Customs Counter – which used to be full of snaky queues of foreigners – in about 10 minutes, picked up my luggage and hopped on a taxi to my apartment.

During the pandemic, empty customs lobbies became a norm at every metropolitan airport. Singapore Changi International Airport was handling very few flights too, when I arrived two weeks ago on January 8. The pandemic also made unusual traveling purposes sound acceptable. When the Singaporean Customs Officer asked me about the purpose of my stay in Singapore, I answered, “I want to enter the US in 14 days.” The Officer nodded silently at my answer, which would sound weird in a pre-pandemic world. Later, I overheard a student-looking young man answering in a similar fashion to another officer.

When I told my friends in the United States of my self-imposed refuge in Singapore, it bewildered them. A year ago, President Trump issued a travel ban restricting travelers who had been to mainland China in the last 14 days from entering the United States. To circumvent the restriction and arrive in the US, mainland travelers like myself resorted to staying for 14 days in a third country which not only welcomed travelers from China, but also posed little risk to the US.

Excluded from the US restriction, Singapore was a viable option for Chinese travelers. On November 6, 2020, Singapore began to receive Chinese passport holders, after mainland China reported a COVID local incidence rate of 0.00009 per 100,000 people over the past 28 days (Channel News Asia, 2020). In the same month, case numbers in the US were climbing, with 371.08 per 100,000 people, the highest 7-day average case rate in November (CDC, 2021). Based on the data, Washington’s insistence on banning Chinese travelers seemed more political than practical.

At both JFK and Changi, the experience as a flight passenger was smooth, but there were some differences. After I picked up my bags in Singapore, I followed instructions directing me to a testing center located inside the arrivals hall. Having prepaid before departure, I got tested immediately and was instructed to stay in my booked room at one of the quarantine hotels to await my test result. The hotel workers sent me to a designated floor reserved for quarantine guests and told me that food and deliveries would be dropped at my door.

The result came out fast. In 7 hours, I received a negative indication via email and was freed from my quarantine room. If you read about the quarantine experience in Singapore on English news media, the tone may have been less delighted. Travelers flying from European countries and the US are subject to 14 days of mandatory quarantine, regardless of test results at the airport. A Columbia Journalism affiliate who quarantined in a hotel shared that she was given a single-use room key, which was only valid for 20 minutes after check-in (Low, 2020). Breaching quarantine law meant severe punishments, including heavy fines, imprisonment and even losing Permanent Resident status for foreigners. Because I had flown from China, I was able to enjoy the rest of my stay as a true tourist. The mandatory quarantine regulation, which has been strictly enforced in Singapore and China, had been carried out weekly in the US. In New York, quarantine rule breakers were seldom punished and the state depended heavily on the travelers’ integrity for observing quarantine rules (Dorn, 2020). Flying from Singapore, a low risk country determined by New York State, I was neither required to quarantine, nor given a test upon landing.

As I explored the city, Singaporean streets looked almost no different from a pre-pandemic world, with the exception that every person wore a mask. On a weekend afternoon, visitors were sometimes shoulder to shoulder at the malls on Orchard Road, the most popular shopping district in the city. Later that night, I went to a semi-outdoor food court at Bugis – a hip, local neighborhood where restaurants selling street foods were packed with customers.

The vibrant street scene did not surprise me because my hometown Beijing had also recovered well from the pandemic. When I took the subway to work in Beijing, the compartment was so crowded during rush-hour that people had to wait for a second train. Yet, the bustling street scene stood in sharp contrast to New York City where I now live. Last week a friend commented that Midtown Manhattan, where every tourist used to go, was “dead.” I felt the same when I was on campus, reminiscent of College Walk so populated with students.

The recovery in Asia was not achieved without “sacrifice.” Prior to my departure to Singapore, I had to show airline employees at the check-in counter in Shanghai Pudong International Airport that I had installed and activated the TraceTogether application on my phone. The app uses bluetooth to track other TraceTogether devices within six feet distance from the user, and the installation and activation of the app are mandatory for all travelers prior to their departure to Singapore.

Whenever people entered an indoor public space in Singapore, they scanned a Safe Entry QR code which registered their visitation. The same registration system was also applied in China, using built-in features in multiple popular apps such as Wechat and Alipay.

In Asian countries, people seem to be more comfortable with disclosing their personal data to disease control agencies. At first, when I was told to register at every shopping mall and restaurant I wanted to visit, I was reluctant. But I succumbed, noting that data privacy was not on the agenda of discussion in Chinese society, and complied when I desperately wanted to hang out with friends at my favorite bar. The Asian governments were successful in cultivating a consensus that sharing personal data was in the public’s best interest. By building trust, public agencies could then deploy this personal data for the public good.

Having lived most of my life in metropolitan areas such as Beijing and New York City, I was used to picturing rural issues as remote from my personal life. When the pandemic broke out in Wuhan and other major cities in the globe, I thought of public health as a huge challenge that densely populated cities would face. However, this January, I realized that it has been a misconception that cities are more vulnerable to infectious disease than rural areas. A couple of days after I left my hometown Beijing, I heard from my family that the municipal authorities were tightening up pandemic controls due to the discovery of several clusters of cases in the nearby rural areas. Streets became quiet again; people were advised not to travel for family reunion during the Spring Festival; mass testing was initiated in affected neighborhoods. My family canceled plans for vacation.

Local news described that the populous, rural area with inadequate health care service had been a loophole in the country’s containment effort (The Strait Times, 2021). Authorities attributed the spread to a combination of the rural residents’ low health awareness and an ill-prepared rural clinic system loosely incorporated into the national epidemic monitoring mechanism (The Strait Times, 2021; China Daily, 2021). Research also indicated that rural communities received little government aid of any sort and suffered a number of consequences such as high unemployment rates and reduced household income (Wang et al., 2021). The local news report also called it a “misconception” that the risk of infection is higher in urban areas than in rural areas (The Strait Times, 2021).

In the US, rural infection rates surpassed those in metropolitan areas in August 2020 (Marema, 2020). The spread of COVID on farms, meatpacking plants, prisons, and nursing homes created substantial impacts on marginalized and vulnerable communities in the countryside, where rural residents lack accessibility to quality healthcare and are excluded from fiscal relief (Ajilore, 2020). In comparison, Singapore’s disease control was a largely urban story. Unlike the US and China, which faced issues of containing the infectious disease in their vast rural lands, Singapore was able to swiftly mobilize its resources majorly located in a highly urbanized physical environment. Although urban density has been seen as a disadvantage to containing the spread of disease, cities such as Singapore enjoy advantages of advanced amenities and well-managed disease response systems.