Preface

Letter from the Editors

For centuries, designers of the built environment have deliberately exploited racial tensions by segregating neighborhoods and perpetuating white supremacy. The events unfolding over the course of this past year are devastating reminders that systemic racism continues to plague our society. Meanwhile, a global pandemic continues to underscore and arguably amplify spatial inequities in our built environment.

As students of urban planning, we have an obligation to dismantle the oppressive systems and racist policies that our discipline has enabled in the past. We are uniquely positioned to unlearn whiteness and create equitable spaces for inclusion.

As such, Dialogues hopes to spur conversations and actions by positioning itself as an issue for reflection and discourse leading to action. From autobiographical experiences on racism, to research papers on spatial exclusion, to statements of advocacy, this Fall’s contributions capture our community’s thoughts and reactions as we witness legacies of social and spatial injustice unfold across different geographies.

We want to thank our writers, junior editors, and coordinators for making URBAN possible. Dialogues is only the beginning of a long and challenging road ahead. Our work will not be complete until we, as planners and people, make reparations for past harms and proceed to truly reform our built environment.

URBAN’s Senior Editors,

Tihana, Geon Woo, & Zeineb

1

My Identity & Me: Thoughts from the Quarantine Cave

Source: Riley Burchell

I’ve been fortunate enough this year to spend most of my time in social isolation eating cheese, watching piled up TV shows and movies I had neglected, and Facetiming the family dog. It’s had its moments; don’t get me wrong. But as I vacuum up detritus from another day of snacking well spent, I can locate my own experience in the larger state of things and know that, all in all, I’m fine.

So, it’s been okay. But it’s also been scary. And as national conversations surrounding the killing of George Floyd and police brutality against Black and African American persons in the US continue to gain momentum, it has driven me to reassess and evaluate the way that I have chosen to take part in the outside world.

I am a Korean American transracial adoptee. My parents are white, my brother is white, and I grew up in Upstate New York that is 97% white. The first time I was in a room with more than one other Asian was during my college’s first day orientation. As a kid, my existence was protected by its proximity to my parents’ whiteness. In the ‘90s, the thing to do with kids of color was to pretend that you didn’t notice any difference—the colorblind approach. While most practitioners today advise against such an approach, many adoptive parents back then were told that it was the most effective way to assimilate an adopted child into their new culture and surroundings.

The problem with that was, as soon as I grew old enough, my life became too big to exist solely under the shield of my parents’ privilege. Suddenly, I had to deal with explicit and unabashed judgements of my person based on a birth culture to which I had no relationship. Navigating the paradoxical nature of my existence in, around, and between these identities—touching both but unable to fully claim either—I found myself switching back and forth depending on my surroundings. More often than not, this meant a mimicry of whiteness’s oppression of blackness in the hopes of camouflaging my own reinforced racial shortcomings.

Until now, my consideration of my position on these things has largely been personal, but being a student at GSAPP, events of the past year have challenged me to locate these conversations in the context of the planning discipline. As planners, we are collectively tasked with helping communities carry out a vision for the place in which they live. In doing so, we strive for accessibility of goods, services, and amenities–things that support a basic quality of life. But of course, just as the planning process is not exempt from external social and political pressures and variables, planners aren’t produced in an academic vacuum; it is life experience that creates the lens through which planners engage in these processes. The question is, if this convergence is impossible to prevent, and if the coalescence of planning theory and the practitioner creates the practice, then what is the ethical path forward?

In a personal context, what does it mean to live, to work, and to play responsibly as a person who has both benefited from and been harmed by her own proximity to whiteness. Building on that, what does it mean to hold elements of both Asian America and White America in one’s own identity politics and use the position that they afford to promote social equity especially as it pertains to anti-Black racism and communities of color?

More often than not, conversations about this with my peers end up sitting in the realm of the non-specific, general self-imposed queries about navigation of whiteness in the workplace and reflections on the long ingrained and internalized essentialisms—that have, for so long, shaped the way we interact and, transitively, the way we engage as planners.

Like many professions, planning has had to adapt to virtual environments; the landscape of practice and what it means to be a practitioner has changed drastically in the past six months. But at some point, life will begin to move once more and, at that time, we will be faced with an opportunity—to take the quarantine conversations and Zoom mediations of the months prior inform the way we plan think through issues of space and place.

Riley is a dual degree student in her final year with the UP program at GSAPP and the Social Work Policy Program at CSSW. She likes hiking and soft pillows, & can usually be found raiding the snack drawer or looking at pictures of her dog.

2

The mysteric racial dynamics for individual identities and values

*Source: Xifan Wang*

I couldn’t help but notice the number of people staring at me on the street. Some asked, why wear a mask if you’re not sick. Back then, in February 2020, my family and friends bombarded me with information and rumors about the coronavirus. As a Chinese international student living in the US, I had and took the privilege of obtaining information from both mainland China and the US. Most of the time, messages conflicted with one another, and I had a hard time reconciling them. At times, even I questioned the whole mask-wearing thing. Although I am aware of the strong scientific arguments for mask-wearing, I hesitated because of the way people reacted to my appearance as an Asian, or, more specifically, a Chinese woman – with ideology stereotypes. For those who stared at my mask-wearing in February, I was the embodiment of China.

In the spring, others experienced more extreme behaviors than staring. An asian man was spit on. A woman wearing a mask was blamed and attacked in public. All these events underscore how stereotypes affected Asians during covid-19. The spike of racial attacks during the covid-19 outbreak contradicts the seemingly inclusive environment of New York City and reveals underlying problems. The interesting thing, however, is that when people think they’re attacking the identity of outsiders, it’s really not the case.

“Asian” applies to people from China, I guess. I do feel like an outsider as someone with an F1 visa, living and studying in the US. It is true that Chinatown is the place to go as an international Chinese student. As soon as I settle in a new city, I go there for the food, the people, and the culture. But I had to admit that when I’m standing in front of a retail store with characters from my hometown yet in a different continent, I have this weird feeling of being somewhere “in-between.”

Like many would ask me if the dish is authentic Chinese. I’m asking myself if this is authentic. “Kind of” is the answer, I think. The city made the effort to be inclusive, but it ended up culturally segregated. There’s something here that just makes me feel both close to and alienated from the Chinese culture. It’s even more weird when I realize that I don’t perceive myself as the same as New Yorkers living and working here. I’m always impressed by my family friends who live in isolated areas where English is not well-spoken, and, in such a New Yorker way, speak Shanghainese all the time. “Asian” applies to Chinese Americans, I guess. Inability to speak fluent English doesn’t mean they are not valuable citizens or they are an inferior class, but makes it difficult for them to communicate or express their feelings to a point that their direct voices are often unheard. It reminded me that one time when I had my blinds fixed before heading back to China. The super came in and began his work after I described the issue.

He saw me packing: ”Are you traveling back to your hometown?”

“Yeah, to China.”

“Oh you are from China,” he seemed to be genuinely surprised, “you speak English well.”

“You know, these people living here. I could barely understand them.”

His sarcastic remarks made me uncomfortable.

I knew which group he’s referring to. But at the same time, I understood his frustration.

He must have thought I was an American-born “Asian”.

Under the big umbrella of “Asian,” there exists many communities who would label themselves differently, distinguishing them from the other. The fact that this labeling system hits both explicitly and implicitly just reveals how complicated the issues are. When we are trying to perceive ourselves and the world, the media often labels us “Asian”, “Asian-american”, “ABC”, etc. and as we perceive along the way, we become part of this labeling process.

Often, when I encounter certain behaviors, I would hesitate to conclude whether it counts as racism. But what would be the answer if a non-first generation Asian immigration is asked about their perception of racism? Do they have a sense of safe space in the city? Is Asian American in the center of the issue or Asian people as a whole?

Racism might be an academically well-defined term but hard to apply in daily situations when it’s more about subjective perceptions. The complexities of Asians as racialized subjects raise an interesting question: how can one deal with the racial dynamics, when the narrative for individual stories is scarce and often ignored? The word “Asian” is never enough to describe any of us.

Xifan is a second-year graduate student in Urban Planning program at GSAPP & holds a BS in Environmental Resource Management. She is pursuing concentrations in International Development & Urban Analytics & serves as the president of the Urban China Network for the 2020- 2021 academic year.

Iwamoto, D. K., & Liu, W. M. (2010). The impact of racial identity, ethnic identity, asian values and race-related stress on Asian Americans and Asian international college students’ psychological well-being. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 57(1), 79–91.

Palmer, E. (2020, February 6). Asian Woman Allegedly Attacked in New York Subway Station for Wearing Protective Mask. Newsweek.

Parnell, W., & Parascandola, R. (2020, May 4). Asian man on NYC subway blamed for coronavirus, attacked. New York Daily News.

Shih, G. (2010, May 2). Attacks on Asians Highlight New Racial Tensions. The New York Times.

Starkey, B. S. (2016, November 3). Why we must talk about the Asian-American story, too. The Undefeated.

Tavernise, S., & A., R. (2020, March 23). Spit On, Yelled At, Attacked: Chinese-Americans Fear for Their Safety. The New York Times.

Wang, C. ‘You have Chinese virus’: 1 in 4 Asian American youths experience racist bullying, report says.

Warfield, Z. J. (2020, January 16). Are Asian Americans White? Or People of Color? Yes! Magazine.

3

Reframing Paris: Les Olympiades, XIII Arrondissement

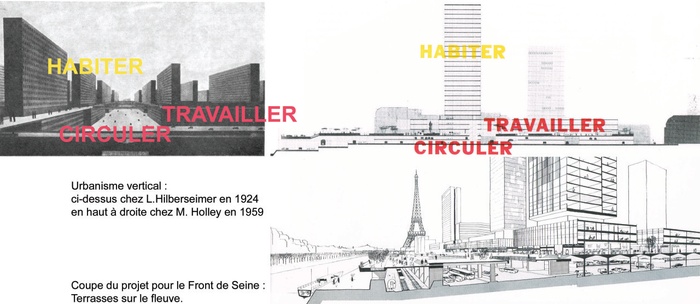

For our Histories of European Cities class, we investigated Les Olympiades, Paris. The neighborhood is situated in the 13th arrondissement and is considered part of the largest Chinatown in Europe. Les Olympiades was initiated under the Italie 13 project, a large-scale urbanism project of Paris, spearheaded by architects Raymond Lopez and Michel Holley in the 1960s. The complex was built with heavy influence from Le Corbusier’s Athens Charter, which emphasizes functionality in the built environment. Hence, this complex has utilized vertical urbanism, a typological approach that optimizes land area by configuring spaces upwards, dedicating layers to different functions.

Presently, Les Olympiades is inhabited by immigrants (predominantly Vietnamese-Chinese), and parts of the vertical urbanism have become a refuge for people who live in poverty. Notably, Paris’ city planning is a socio-economic gradient - wherein the peripheral area of the city is mainly for people with lower-income or middle class status and the inner city for richer communities.

Through rigorous research methods (you might name them), this project explores the realized effects of Les Olympiades’ planning and its implications in the vicinity for its current and future inhabitants.

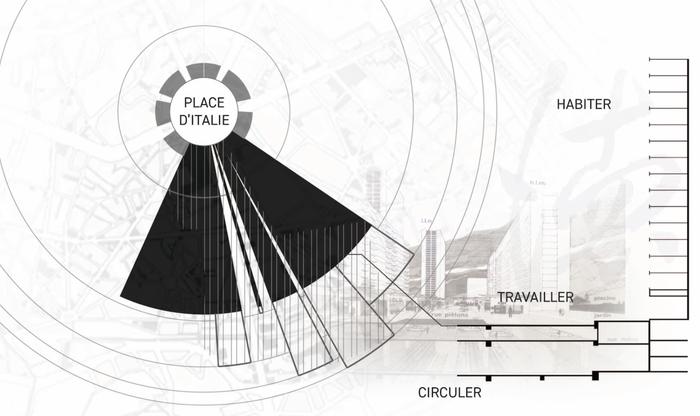

This thematic map-collage compares the verticality in built form of the realized Italie 13 project with the existing urban form. The diagrammatic radii centered around Place d’Italie shows the average height of the build density (lower to the North of Place d’Italie, and taller to the South, where Italie 13 projects are situated). The map is collaged with a section drawing of an example of the Italie 13 projects using the Olympiades, outlining the functions. The Chinese character for “virtue,” taken from the book Paris XIIIe - Lumieres d’Asie, is illustrated as a ‘future prediction’ of the eventual unpredicted Asian migration to the area.

While Le Corbusier’s Athens Charter and the American Planning Theory’s were framed as potential solutions towards improving urbanism, the realized built form of Les Olympiades underscores the shortcomings of the plan. As seen in the diagram of sun dynamics, the towers do not provide equal access to natural light in all areas in the complex, and instead are hovered by shadows. Only during noon does the complex achieve optimal sunlight (looking towards the valley facing south to north).

There are different gradients of light in the different levels of the complex. Apartments on the towers, schools and businesses facing outer Olympiades receive the most sunlight, while the covered mall has only natural light seeping through doors and open slits, and old rails under platforms have least sunlight. Some people under immense poverty also utilize the dimly lit layers of the vertical complex, that is where sunlight is the least, as places for shelter.

The Sociological Aspect in Les Olympiades’ Present State

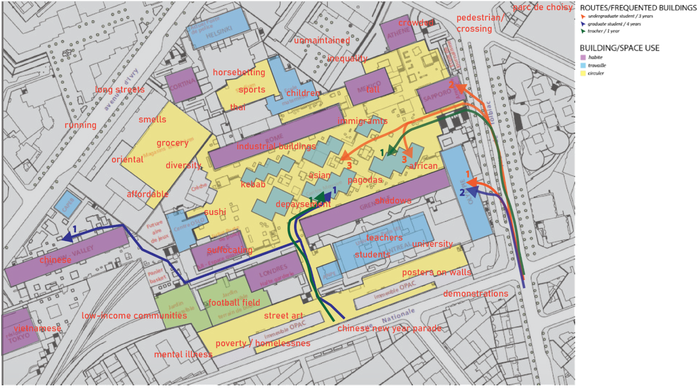

We interviewed a resident — Nicolas Le Bléïs — who has resided in the vicinity of Les Olympiades for more than eight years (during different life phases) to answer these questions: How are the spaces functioning in Les Olympiades presently? What are the routine paths within/around Les Olympiades in your different life phases? During your time in Les Olympiades, what have been your most utilized spaces? His responses are summarized in the map below.

Currently, the most pressing issue that Les Olympiades faces is poor maintenance. Situated in outer Paris, the Parsian government allocates an inadequate proportion of its budget to the site. However, the neighborhood is still enjoyed by many. Le Bléïs encapsulates his current reality of Les Olympiades through a mental map. We also included Le Bléïs’ thoughts on the race dynamics between Asians and non-Asians in Les Olympiades, with the current demographic being mostly Chinese/Sino-Vietnamese (immigrant communities).

Nicolas Le Bléïs’ interview

Do you think there is bias of benefits between Asians with respect to these parameters? For example, food is mostly Asian food, is this a disadvantage for non-Asians (in your perspective)?

“I think there is a bias in benefits, since I am under the impression that Asians mostly hold unqualified and underpaid jobs (cashiers, waiters, etc.) whereas most qualified jobs are held by non-Asians, and most students in the university are not Asians. Public amenities are open and diverse, and since healthcare is free for all, Asians benefit from doctors and pharmacies in the same way. In terms of food, the fact that there is mostly Asian food attracts new customers who are driven to Olympiades to experience foreign cuisine. This tends to increase the prices, since those new customers are richer, and have higher standards in terms of hygiene/cleanliness, products quality, atmosphere, etc. These changes may impact disproportionately those Asian workers who are underpaid.”

We are looking into race dynamics in our project since the 13th and Olympiades is home to Sino-Vietnamese and Chinese communities. As living in the 13th near Olympiades, are there any race contentions between Asians and not Asians?

“As far as I’m concerned, I have never seen or heard about any race contention between Asians and non-Asians. Although most races live in separate apartments for family reasons, most buildings are shared amongst people from different races, and there seems to be a diverse background to the neighbourhood (although influenced by Asian culture). I would say that Asians are held in high regards by middle-class and upper-middle class, who enjoy the atmosphere of the neighbourhood, and the amenities. Friends of mine, from North African descent, and who happen to be muslims, enjoy the company of Asians and find their restaurants to be a lot more compatible with their food restrictions than others. Everytime they have asked for a specific menu, they have been treated very nicely, and with care, which to me implies that this is a common request. A lot of students from the university closeby are also very tolerant and open to diversity, which creates a deeply cosmopolitan environment. In my personal experience, I have never been treated badly by any person from Asian descent, be it by someone working in a company/restaurant, or by a passer-by.

The only contention that might exist, but I highly doubt it happens in Paris, has to do with the fact that Asians have a reputation (unclear where it comes from) to carry a lot of cash. That makes them more vulnerable to pickpockets or attacks, but I’ve never heard of such stories in Olympiades, only in the suburbs where poverty and crime are statistically higher.”

Sherry Aine Te, Maximilien Chong Lee Shin and Valentina Gamero were students of the 2019-2020 GSAPP New York/Paris program. During their time in Paris in Spring 2020, the team was able to explore Paris in an alternative lens, until the pandemic halted their adventures.

APUR. (2001). Report on 13th Arrondissement. Costa-Lascoux, J. and Yu-Sion, L. (1995). Paris-XIIIe, lumières d'Asie. FR: Autrement.

Downie, L. (2012). Paris: Under Construction.

Hauer, C. (2018). Paris: Les Olympiades, ultra-moderne solitude des architectures urbaines - XIIIème.

Holley, M. (2011). Urbanisme vertical & autres souvenirs. FR: Somogy.

Moiroux, F. (2013). Les Olympiades, Paris XIIIe :une modernité contemporaine.

Texier, S. (2000). Le 13e arrondissement: itinéraires d'histoire et d'architecture.

4

Bilal’s Adhan

Bilal ibn Rabah’s story, may God be pleased with him, sets the immediate stage for how anyone who submits to God is demanded to view race – never something that determines human value. Bilal was a black slave who was of the Prophet Muhammad’s, peace be upon him, closest companions, and exalted as one of the most beloved Muslims, as he valorously made the first call to prayer ahead of Pagan Makkah’s public. The historical accounts describe Bilal’s voice as that which brought the entirety of crowds to tears, if not intense focus. Everyone who has visited Istanbul or Marrakesh, be it a mountain shepherd or Liam Neeson, is soulfully taken by the call to prayer: the adhan.

Malcolm X famously stated that the only cure to America’s racism is Islam, most evidently after he left the Nation of Islam for Sunni Islam. For anyone interested in ending racism in America, with any respect for figures like Malcolm X or Muhammad Ali, should consider the root of what led them to be two figures of quite an incomparable continuity in nobleness and strength in their character, compared to truly any other Civil Rights mover.

Bilal was famously the most tortured Muslim in the early Islamic history. He, being a black slave, had no protection when he first converted/reverted. However, while he was dragged on the coal-hot rocks of the Arabian desert, he would continue to testify the one thing that makes Muslims different from anyone else – their testimony to no deity except Allah, and their acceptance of Muhammad as a prophet. He inspires and tears-up the likes of any Muslim, child or adult. We think of the strong reformative stance Islam had on freeing a slave, and the strong Quranic virtues of racism being a clear error of arrogance, whilst sustaining its anti-aggression norms, this poem provokes the history of Bilal for those who have and have not heard of the black Muslim’s voice, ringing the desert that deserted him.

Without contradiction, and incredibly clear fact, the will of Allah treats racism as wrong, and by the virtue of Malcolm’s view, Islam, in its uniqueness to how it singlehandedly banded people together regardless of race, unlike any other ideology, must be a pointer to something deeper. Hence, I begin the poem: There is a voice to be heard / That is quite yet been muted.

There is a voice to be heard

That is quite yet been muted.

Makkah’s slaved, black man’s rhyming tongue

Carrying a cure to the believers in their every abused moment.

A call to provoke peace,

To acknowledge how we were created,

Was the single greatest march in history

That could see passed the tribe-striped race, that has us separated.

From high and low places,

In their call for justice, a truer Peace seems evaded,

By the unchanging truths that six centuries past,

Had the torturer’s hearts and horses abated.

From a black man’s echo, the words would be Forever reverberated:

God is the greatest,

I testify that there is no God but Allah

I testify that Mohammed is God’s Prophet

Hurry to connection with God

Hurry to success

God is the greatest

There is no God but Allah.

5

Purple Plantation

A poem in response to the death of George Floyd by knee. A purple plantation is something beautiful – cotton is beautiful, the color purple is beautiful, and this honors that those things symbolize something greater. Whilst race is not a matter, if we were to identify people by race, let us identify is based on their deeds – exalted and brought down to provoke change and engage with uplifting demeanors.

The spilling of pillage is happening like decanter,

Its fillings are setting its wastebasket afire;

Ablaze is the moment we are after,

Where a peoples are healed.

My oath that justice is the Master,

And only for He is there call, for slavery,

But your knee took man back to plantation,

I suppose you then reckoned cotton was great because of its white breed;

What a pricking pick you came to be.

But do not you dare call yourself white like a feather,

After all, a man’s submission is whereon he places his knee,

For you are pale as death comes –

And that man naught black like coal!

That man naught black like coal,

Even if his death lighted a smoky flame,

That human, who you treated as cotton-picking poultry,

A shingling anti-Schindler to the word of humanity,

Is, rather, purple like royalty.

Ali Ahmed is a Muslim poet and designer, raised in 7 countries worldwide. Above all professions and identities, his work intends to craft intellectually flourishing places in which God’s remembrance is facilitated and elevated. He has worked as NASA’s space suit designer, Norman Foster’s apprentice, Autodesk’s CEO, and intends for a future designing mosques, farms that promote the ethics of Halal, and writing books of poetry.

6

Who’s Loitering?

Sirens, car horns, an enthusiastic group of young men on super-bikes, and sporadic but passionate cursing by no one in particular – my neighbourhood in New York City is loud. The denizens at the corner of 109th and Columbus are perpetually assaulted by a barrage of transient sounds of all kinds. The more pleasant of these, however, is the music broadcasted to the general vicinity through much of the day. With the windows thrown open to the last of the good weather, I spend a lot of time at the dining table reading for my classes with the infectious Latin beats for company. Sometimes there are cars that drive by with hip-hop music drowning out the bachata. This usually lasts as long as it takes the vehicle to reach the end of the block, sometimes longer if it decides to park. Then it turns into a ‘war of volumes,’ until - I’m guessing - someone gets bored or a truce of some kind is declared. I’ve tried craning my neck over the rusty fire escape to catch a glimpse of these DJs and maybe their audiences. But the trees, and more likely, the disadvantageous position of my window has not yielded any fruitful sightings to date.

While running errands or waiting for the dryer to complete its cycle, I’ve walked around the neighbourhood in search of this music. Sometimes I think it’s coming from the church at the end of the street - but its doors are always padlocked and its message board is empty. Other times, I get close enough to feel the bass through the sidewalk but there’s never anyone around. The echo off the buildings, the closed windows, and their drawn curtains make it hard to say with conviction that the DJ is indeed up in one of these apartments. The parked cars on either side of the narrow street never have anyone in them. In fact, I don’t believe that I’ve ever seen one pull in or drive away in the month that I’ve lived here. The neighbourhood is alive - it certainly sounds like it - but there doesn’t seem to be a soul in sight. Then one day, I noticed a sign painted on a wall next door, just below eye level behind a metal gate of sorts.

“NO LOITERING,” it said in no uncertain terms. I was thrown. It seemed to contradict the reclamation of public space all over the city since early April this year: parks inundated with people, sidewalk cafes and road closures that transformed entire stretches of what were once busy streets into socially-distanced living rooms and backyards. Some even became venues for book clubs, soccer tournaments and the like, all being played out simultaneously. I was even more confused when I began to take notice of the things that were occupying the sidewalks in my neighbourhood: trash bags, battered furniture, a toilet on one street corner, dilapidated (and frankly, redundant) phone booths, and the ubiquitous red-and-yellow newspaper boxes that most certainly do not contain newspapers. No loitering? To loiter is to ‘stand around idly with no apparent purpose.’ A mouldy brown single sofa sits outside my apartment right now. Isn’t it the real loiterer?

‘No loitering.’ Who is a loiterer and what characterizes their loitering? The dichotomy of this writing on the wall is easy to overlook as one power walks by it to ‘wherever.’ It is both benign and hostile, either directed at someone specific or no one at all. This obscurely painted sign is dangerously explicit or implicit depending on the eyes of the beholder – the homeowner, the citizens of the neighbourhood, the lawmaker, the enforcer, the policy maker, the urban planner. In a metropolis that has long claimed to be the epitome of urbanism, the embodiment of “a place where differences encounter, acknowledge, and explore one another” (Schmid, 2012). This phrase – a double negative – seems to be tragically out of place, especially in the on-going pandemic that unmasked the deep societal inequity . Are my neighbourhood’s DJs and their audiences loitering? Is that why they’re sequestered somewhere?

Nupur Roy is an architect pursuing a Master of Science in Architecture and Urban Design at Columbia GSAPP.

Schmid, C. (2012). Henri Lefebvre, The Right to the City, and the New Metropolitan Mainstream. In Brenner, N., Marcuse, P., & Mayer, M. (Eds.), Cities for People Not For Profit: Critical Urban Theory and the Right to the City (pp. 42-62). Routledge.

7

“Rolezinhos” and discrimination in Brazil

On December 7, 2013, over 6,000 adolescents from the age of 14 to 17 gathered for a “rolezinho” in a shopping mall in Itaquera, a neighborhood in the East zone of São Paulo. Usually arranged by social media influencers, this was supposed to be another “rolezinho” for them. Middle-and-low-income teenagers, mostly black or brown, stemming from the peripheries of the city gathered to enjoy a modern amenity, a shopping mall.

Unbeknownst to them, this “rolezinho” attracted the attention of the media. After gathering in the parking lot, teenagers entered the shopping mall en masse. Many shop owners were taken by fear and saw the event as an “arrastão,” a mob or collective robbery. They falsely claimed that goods were stolen by the teenagers. The police were called, chased teenagers away, threw tear gas, and shot rubber bullets.

What was supposed to be another encounter to flirt and meet with friends became a violent battlefield within a matter of hours. The police justified their actions to prevent an “arrastão.” Observers claimed that they saw teenagers drinking alcohol and smoking marijuana. A video, showing a teenager bragging about his stolen sneakers, became viral. Yet, there were no charges for robbery or vandalism and the mall administration affirmed that there was no known case of theft on that day.

Debates on spatial exclusion and discrimination are central to contrasting viewpoints of that day. There are certainly many distinct perspectives on the significance of the “rolezinhos.” It can be understood as one expression of a new rising social class, a result of the economic development following the re-democratization of the country after a military dictatorship. Or even that it was a movement that enabled invasions of personal spaces and violences to spring on every stakeholder involved. However, this event has once again put in evidence a veiled bias on race and class that is prevalent throughout the nation.

Nonetheless, this is not a new observation; it still upholds its relevance. Following the Black Lives Matter movement that reverberated across the world, many Brazilians might indicate that racism and discrimination are not profusely evident or discussed in Brazilian society. Yet, there is a strong underlying current of social stratification and attribution of value depending on your race, origins, educational background, and social class that permeate individual perceptions of others and that impact and shapes our cities and policies.

From the “rolezinhos,” this differentiation from the other can be more quickly perceived in the commentary section of a Youtube video depicting the social gathering in the parking lot of the Itaquera shopping mall. Amongst the 42 comments, only one showed support, while the rest used words such as: rotten race, kill, children, prostitutes, criminals, vagabonds, lack of education (Martin, 2013). The aggressiveness of the commentaries shows the accumulation of unjustified hatred between two groups. There is a high level of frustration that has been wrongly canalized onto the other group.

After the Itaquera mall incident, other “rolezinhos” were planned on social media but the mall’s administrations soon sought legal injunctions to bar these encounters. The rulings clearly juggled a conflict of interests and, in these cases, favored the mall administrations. Security guards were stationed at the doors impeding underage people unaccompanied by their families from entering the premises. There were a handful of other requested injunctions throughout the country that were in fact denied, as these unconstitutional impediments were seen as unfounded and based solely on rumors of violence and robbery.

As the majority of court orders has demonstrated, the public sphere commonly corroborates this social valuation that is so pervasive but unvoiced. The civil society ends up suffering serious consequences that can impact generations. The development of the Água Espraiada Avenue in the southwest part of São Paulo is an example that materialized the effects of such valuation. In an area where thousands of low-income families in informal residences were established for decades, a massive displacement project occurred leading them to peripheral areas of the city. What entailed was an elitization of the region, which now has achieved an exponential elevation of land values and the investment of numerous transnational companies.

Considering how these events have transpired very recently, what remains evident is the need to maintain the recently-awakened momentum of discussion and action.

Thiago Lee holds a Bachelor of Architecture and Urbanism from the University of São Paulo and is currently a candidate for the M.S. in Urban Planning and M. Architecture at Columbia GSAPP.

Martins, J. [Joel Martins]. (2013, December 9). Marginais causam tumulto e arrastão no Shopping Itaquera [Video].

[vmbarbara]. (2014, January 12). Rolezinho no shopping Metrô Itaquera [Video]. Youtube.

8

The Sacred Space

Covid-19 is reshaping public space, or at least for now, it is reshaping our behaviour in the public realm. After the citywide lockdown in the early months of the year, New Yorkers oscillated between yearning for the outdoors and fearing the pandemic that claimed the lives of many. The various typologies and liveliness of public space in the city were enticing enough to get people out of their homes. Whether it is riverfronts, beaches, lawns, plazas or promenades, people went out. As a result, the emergence of the sacred unit of 6 ft was introduced into our collective imagination as medical experts continuously preached this unit as the safe bubble that we must abide by to stay safe. The Sacred Space is indicative of a privileged lifestyle where people bathe in the sun and enjoy the summer, rather than having to queue for basic necessities such as water, food, or medicine.

Representation of the Sacred Unit began to appear in the public sphere in all sorts of forms; fences, sprayed circles on the ground, tables and benches with a 6 ft diameter, 6 ft picnic blankets, and whatever that could be used to represent it. As an observer of the built environment, I was eager to explore the relationship between people’s behavior and the Sacred Space. Did the form of representing the Sacred Space affect its effectiveness in people abiding by it?

The pandemic led to unconventional ways of exploring the city and documenting this phenomenon. Public transportation remained a relative risk especially in the early stages of the pandemic, so I took on cycling around the city to discover this new relationship. The planar aspect of The Sacred Space posed a challenge to observers on the ground level. If our understanding of 6 ft was already skewed and needed representation, then imagine trying to document this relationship in the same manner. The exploration broke the two dimensionality of the ground and further navigated in the z plane to document the Sacred Unit through drones and helicopters.

The photo essay which explores New York City’s vital public life in this critical time invites us to consider the relationship between our collective behaviour and representations of the Sacred Unit.

Bisher Tabbaa is an Architect and Photographer who is currently pursuing a Masters in Architecture at Columbia University GSAPP.

9

Minority on the Border: Integration & Reconfiguration

INTRODUCTION

Humanity has been intertwined with nature since the first day they struggled to survive. Hence, the constant interactions between the two have constructed splendid historical and cultural heritages for posterities. However, we must remain vigilant about the epistemological shortcomings here. Although intriguing, the disadvantages brought out by this binary opposition are obvious, the struggle and complexity of the real situation with euphemistic details and self-contradictions may be ignored by simplification and obscured by essentialization. That is to say, “human” and “nature” are never self-explanatory, pure, and static concepts or subjects, of which both connotations need to be distinguished and explained in specific situations, spatiotemporally. Only in concrete space-time coordinates, can we historicize and materialize our exploration.

Therefore, this paper does not attempt to rationalize and legalize the binary thinking pattern mentioned above which has been repeated unintentionally for too long: the power relations are determined by the transcendental nature of two subjects and came along with a strong irreversible tradition. These two concepts are always selectively constructed with highlighting certain characteristics for the sake of specific needs. Thus, they are not only artificially designed and constantly updated, but also a time shifting construction without seemingly solid traditions.

We would like to demonstrate that on one hand, humanity is self-regarded as a powerless feature that requires obedience and reliance on the laws of nature, on the other hand, humanity can also be self-worshipped as a positive master with the right and power to transform or even reproduce nature. Nature, similarly, was in some circumstances honored as sacred and inviolable subject, but could also be vilified as a negative object, the pure “other” of humanity, that could be modified arbitrarily without fear anymore——as “landscapes” to be gazed, “resources” to be extracted, “wild” to be civilized, and “land” to be colonized. Only when these two concepts are first deconstructed and historicized, could some practical questions be effectively analyzed.

Further, we would like to put our attention on the whole “process” of how the power from different aspects in the field, underneath the name of “humans” and “nature”, coexist, shape, and transform each other. Finally, this article will focus all those concerns in one spot: a “border.” Through the example below, we can see how the border was not only generated naturally but also constructed artificially. The process of shaping, rewriting, distorting, breaking, and deconstructing, is driven by political concerns or economic demands, rather than random autogenesis. The example will be a story of a primitive ethnic group from virgin forests, their struggle among diverse borders: of nation-states, regional planning, and modern cities.

CASE STUDY: MINORITY ON THE BORDER

1. The Construction of Border:

1.1 Integration: Nation-state as Framework

“Ewenki” (Эвенки) is a nomadic and hunter-gatherer group scattered in Northeast Asia, especially in Siberia Region. Three hundred years ago, a handful of Ewenkis, herding their reindeers from the upper reaches of the Lena River in Siberia, moved south to the northeastern frontier of China. At the end of a war, they resettled at the northern foot of the Greater Xing'an Mountains, a region of primeval forest on the right bank of the Argun River. They divided into three branches: the Sauron tribe, the Tunguska tribe, and the Yakut tribe (also called Aoluguya). Our focus will be the story of the Aoluguya people.

The Aoluguya tribes spent their hunting-gathering life peacefully in the forest for generations since they resettled. Yet, out of the forests, the geopolitics of East Asia changed dramatically. Mainland China went from the demise of the Qing dynasty, after years of chaos, to the establishment of the People’s Republic of China. An ancient world with blurred borders finally was reaffirmed as a sovereignty with clear boundaries, a feudal dynasty transformed into a new form of nation-state. The Argun River happened to be identified as the Sino-Russian border river. Thus, the right bank where the Ewenki inhabited became a part of PRC. Since then, the tribe is officially recognized as one of the “55 ethnic minorities,” aggregated with the rest of the sovereignty, and dissolving the tribal border politically. Nation-state, as the new framework will be a vital premise for the following discussion.

1.2 Redistricting: Dichotomy between Nature and City

Although, like flows into the sea, the home range of the group has been eroded into a larger nation-state, the new nation’s urban development generated another type of border.

The 1200-kilometer stretch of the Xing'an Mountains is a natural barrier, and the abundant animal and plant resources make these hunter-gatherers self-sufficient with little dependence on the outside world. More importantly, different spatial patterns also foster varying characteristics, laying multiple challenges for future interactions. The Aoluguya tribe, retaining their nomadic lifestyle, worshiped shamanism and nature, domesticated the reindeer around their camp, and through so-called “forest boats” as a means of transportation, traveled among the vast forest and hunted animals, such as bears, meese, foxes, and rabbits. This was a complete departure from the agricultural and urban lifestyle. Gradually, a border was generated spontaneously between the independent natural systems in the mountains and the urban life in the plains.

2. The Re-shape of the Border

2.1 Displacement: Political Intervention

As mentioned above, the distinction between mountain and plain, nature and towns, nomadic and agricultural, gradually formed a blurred “border.” However, at the same time, this natural separation has always been modified by various forces. The most significant one is the interference of political forces with the local government as an agency. In this case, the initial displacement of the border was out of political concerns: the nation-state’s security. In 1965, due to the deterioration of Sino-Soviet relations turn to be intense. Therefore, the Chinese government relocated the Ewenki people from the border slightly inland to Aoluguya riverside, away from the front line, and established “Aoluguya Ewenki Hunter Village.” Since 1957, the local government considered building “MuKeDen,” a Russian style wooden house with a stone foundation for Ewenki’s resettlement. With the relocation, some Ewenki people began to leave their birch bark tents in the mountain camps, moving down to the wooden house. However, they still need to hunt for fur and graze reindeers in the forests. As a result, many Ewenki people started to live a “dualistic life”: moving between the hunting spots uphill and the residential house downhill. Along with this, the border of natural divisions has been broken and modified, driven by political considerations and power. The range of ethnic minority activities has expanded to other regions, and the previously self-sufficiency within nature was remodeled. Gradually, they built more relations with towns, participating in the urban production and consumption cycle. For example, the local government initiated a plan to purchase Ewenki’s reindeer by-product regularly, such as antlers, which has become the most significant source of their income. During these interactions, their dependence of urban commerce and government distribution has increased rapidly. Whether passively or actively, the previous border was reshaping.

2.2 Transition: Economic Driving

More profound changes, also the core contradictions, in this case are no longer the politically-oriented “displacement” in small-scale, but rather the “transformation” further driven by economic development concerns, which may lead to conflicts between government dominance and ethnic traditions.

The government project titled “Ecological Migration,” implemented in August 2003, caused a fundamental change in Evenki’s life. This project involved a brand-new village for the Aoluguya tribe, only five kilometers away from downtown. The infrastructure included office buildings, museums, schools, hospitals, nursing homes, and 62 brick houses for hunters with unified paint colors and heating for the freezing winter, entirely constructed according to the standards of a “modern town.” There are two striking highlights of this over 11 million RMB-investment-project. One is the provision of 48 individual huts, not to resettle the hunters, but their reindeer. Another is the government confiscation of the guns used for daily hunting. These two arrangements ended the dualistic life the Ewenki had previously maintained, even completely desisting their nomadic life without guns for hunting or a need to graze. The lifestyle of the Ewenki people had been transformed into a standard urban lifestyle. The border was completely eradicated and disappeared.

2.3 Space-in-between: “Flâneur”

From natural formation to artificial division, from displacement to transformation, even from fusion to modernity, historical interactions are clearly represented on the border.

However, the story does not always linearly follow the expected direction. Although the local officials’ intentions were good, keenly hoping the marginalized group could take this once-in-a-lifetime opportunity of policy and financial support from the central government. The “Great Leap Forward” from primitive to modern, nomadism to settlement, and nature to urban life was more problematic for the Ewenki than good.

Soon after moving to the modernized and urbanized village, some Ewenki people drove their reindeer long distances to return to the “primitive” camp life in the woods. There were three reasons for their departure. First, many reindeer died to their inability to adapt to captivity, and hunters suddenly suffered substantial economic losses. Second, hunters were facing increased living expenses, such as water, electricity, gas, heating fees, which brought additional economic pressure compared to the camp life before. Most importantly, hunters without guns had nothing to do; modern life without nature voided their previous aspirations and dreams. Official subsidy was allocated to support the re-employment of hunters, but was mostly abused to buy alcohol to relieve their homesickness. Several even lost their lives to alcoholism.

Urbanization seems to have failed the Ewenki people. The problems have not ended here; the consequences of border destruction and the penetration of modernity are irreversible. Returning to the forest did not reduce their confusion, since the youth was already fascinated by the wonders of modern urban life. More practically, they were already economically dependent, the city becoming an “absent presence” in their daily life. Although their bodies were returned to nature, their minds were still attracted to the cities, losing any intention to live a primitive life anymore. Without shotguns, they had no income from hunting nor defense against bear attacks. Any other Ewenki people descended into vagrancy, suspended in “a life of exile” between nature and cities, neither settled nor nomadic. These border issues signified the value of our further critical thinking arising from the relation between humans and nature.

Yuheng Wu hold a B.Arch degree in architecture design and is currently pursuing the MS Real Estate Development at Columbia GSAPP. He worked at Beijing, Japan, Paris as an architecture designer and was interested in researching urbanism issues located in China. Yue Qi is Research Scholar and Visiting Fellow at Harvard University, Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations. She is also a Ph.D. Candidate of Chinese Contemporary Literature in Peking University, Department of Chinese Language and Literature.

10

Monuments: Worth the Retelling?

After my usual Sunday forays down Broadway to Westside Market, I turn right onto the pedestrian-only stretch of 116th Street that spans the width of Columbia University’s Morningside Heights campus. The sun beat down in late September fashion, causing others traversing the long campus block towards Amsterdam Avenue to covertly pull down their COVID-mandated masks to dab hints of sweat from the crevices of their noses, mouths and cheeks. It was business-as-usual; parents pushing prams and newly minted dog moms proudly prancing their pooches.

As I pound home atop the herringbone bricks towards Amsterdam, my gaze first shifts right towards Butler Library, scanning the frieze engraved with its litany of the “best of” ancient classical thought. I say my hello’s to Herodotus, Sophocles, and Vergil. Then, my eyes veer left to the open South Court below Low Library. I take a pause, delighting in the dome, portico and small but happy gaggle of students finally returning to their beloved steps, sunning themselves and snacking on their Shake Shack or Dig Inn takeaway. A small crowd surrounding the 1903 statue of Alma Mater at the center of the court seemed somehow out of place (Dolkart, 1998).

It was not unusual to see someone posing for a souvenir photograph in front of the bronze woman wielding the King’s College scepter in one hand and a gesture of welcome with the other. Today, however, bouquets of peach and white roses, a pot of seasonal yellow mums, and sunflowers lay at her feet. Tucked in between the flora were legal pads in white, yellow and cream. A white poster in a child’s handwriting solved the mystery: Ruth Bader Ginsberg. Another read: Thank You. A third: When There Are Nine.

Looking up, a white collar graced Alma’s neck. Unexpectedly, it came. My chest tightened, the rush of wet rose to the corners of my eyes. A subtle clench of my fists, formed by pride and feeling – feeling that had grown mute given all the year had provoked so far – released. I felt a moment of reprieve. How was it, that in 2020, when the world had been erupting due to global sickness, political upheaval, and anguish over racial injustice – that I, we, the community, were able to find a moment of solace in the most ancient of memorials– a monument?

There is a lot of debate about monuments these days. Asserting their value in the digital, global 21st century, when their presence may invoke feelings of hurt and pain, is a questionable attempt. Activists have condemned them. The Andrew W. Mellon foundation has recently set aside $250,000,000 to rethink them (Schuessler, 2020). Even defining what constitutes a monument is tricky: do mausoleums, museums and decaying ruins count? Are we ourselves nothing but talking statues? According to the 19th century theorist Alois Riegl who contributed to the development of modern, Western historic preservation, a monument is all-encompassing (Riegl, 1903). For Riegl, every work of art is in fact considered a historical monument and the value ascribed to it establishes its worth and importance as such. In the 21st century the value of a monument is more directly derived from the community that surrounds it, supports it, creates it, and takes actions to maintain or even destroy it.

What happens when monuments no longer represent the values of a community? Confederate monuments honor individuals or express symbolisms that imply reverence for a U.S. that justified the worth of a white person over that of a black person. Seeing these monuments displayed prominently in public spaces functions as a reminder to the community of this wrong and constantly exposes unhealed wounds. The Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement has reignited the fight to remove, retake, and replace monuments at a rapid rate (McGreevy, 2020). The movement has also driven the removal of monuments that have reinforced ideas of colonial supremacy and racial dominance such as the Roosevelt statue on the front steps of the Museum of Natural History (Pogrebin, 2020). Since 1940, this statue has greeted visitors from all over the world. The community’s successful call for its removal shows how an assessment of community values can lead to action. Monument free, all visitors will now enter the museum as equals. As the dismantling process unfolds in courtrooms, by committees and by physical means, the worth of a monument seems, well, questionable.

Monuments are erected with the intentional aspiration of permanence: to honor, remember and never forget. In ancient Rome the process of damnatio memoriae removed all physical evidence of an individual (Varner, 2004). Names were scratched out. Statue heads were toppled and replaced. Monuments were not deemed worthy of preservation because their value had diminished in the eyes of the empire. Acts of damnatio memoriae were meant to remove the past from public memory. As we embark on a modern day damnatio memoriae, rightly offering up monuments to destruction and removal, I argue for a brief pause.

Not all wish to remove these symbols of inequality. The Robert E. Lee monument in Richmond, Virginia continues to face legal action blocking its removal (Kolenich, 2020). As the matter pends, however, the monument has been transformed by the community. Spray paint, banners and murals have encased the ode to a Confederate south in a tangible coating. This coating expresses the cry for equality and the end to systemic racism that continues to permeate U.S. policy. Time has allowed this site to become a rallying point for reflection and action. The opportunity for people to engage with the monument allows those that oppose its removal to see firsthand the deep seated pain that comes with a statue that heralds defunct values. The physical symbol gives urgency and realness to a community’s cry and offers the chance for a shift in perspective. This shift could drive what will replace the monument. Perhaps there is value in not fully embracing damnatio memoriae, at least not right away. Time will pass, the emotions of the BLM moment at this exact point in time will become part of history. Maintaining some physical element of the community’s interventions to the monument as the built environment is recast could make for an even more effective and powerful retelling than if the site were fully erased.

Monuments will continue to engage us. They stir up intense emotion, whether it be release in mourning the loss of an irreplaceable Supreme Court Justice, or anger and rage over a government that has failed to right past wrongs. Monuments provide a symbol, a breaking point, and a space of unity for us humans with diverse views and stories. They have the ability to establish a sense of community and push us to reassess our beliefs. By doing so we have a better chance of achieving equality for all. An imperfect symbol of this goal is worth pursuing and, in the end, affirms the utility of a monument in the 21st century.

Rachel Ericksen holds a BA in English Literature as well as a law degree. She is currently pursuing the MS in Historic Preservation at Columbia GSAPP.

Dolkart, A. (1998). Morningside Heights: A History of Its Architecture and Development. NEW YORK: Columbia University Press.

Kolenich, Eric. (2020, Aug 25). After judge’s ruling, Richmond’s Robert E. Lee statue will stay in place until at least October. Richmond Times-Dispatch.

McGreevy, Nora. (2020, June 9). Confederate Monuments are Coming Down Across the Country. Smithsonian Magazine.

Pogrebin, Robin. (2020, June 21). Roosevelt Statue to be Removed From Museum of Natural History. New York Times.

Riegl, Alois. Moderne Denkmalkultus : sein Wesen und seine Entstehung, (Wien: K. K. Zentral-Kommission für Kunst- und Historische Denkmale : Braumüller, 1903). Translation first published as Aloïs Riegl, “The Modern Cult of Monuments: Its Character and Its Origin,” trans. Kurt W. Forster and Diane Ghirardo, in Oppositions, n. 25 (Fall 1982), 21-51.

Schuessler, J. (2020, Oct 05). Mellon foundation to spend $250 million to reimagine monuments. New York Times.

Varner, E.R. (2004). Mutilation and Transformation: Damnatio Memoriae and Roman Imperial Portraiture. BOSTON: Brill.

11

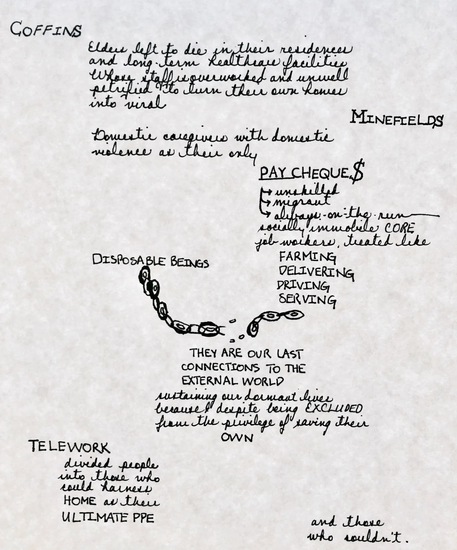

Commoning Care in Barbados: Home Away & Beyond

Until now, global responses to COVID-19 have greatly centered around epidemiological and economic cures, whereas the pandemics’ impacts on our fragile systems of care have only started to be understood. While care is characterized as “clusters of practices and values”, it is a form of labor (Held, 2006) ensuring social reproduction, with carework “performed to fulfill the needs of those who cannot do so themselves, such as food provision, cleaning, health, etc.” (Akbulut, 2017). Months of quarantine have significantly intensified care burdens, known to be borne predominantly by girls, women, and the underprivileged. Despite emancipation, booms of female employment have always been in the service sector. Women traded unpaid housework at home for the “most monotonous, hazardous, least secure and lowest paid” housework in restaurants, hospitals, cafeterias (Federici, 2012), and child care facilities, thereby enforcing and capitalizing on gender stereotypes and segregating spaces for production, consumption, and reproduction. These spaces are now suddenly fused, coronavirus obliged, into one single, hermetic bubble. For many, this amalgamation embodies the ultimate spatial archetype of care: home.

Whether home is prison or privilege largely varies upon how we take care, and have been/are being “taken care of”. In an era of neoliberalizing social care systems underfunded by state agencies, care is indissociable from self. Images of marketed practices around consumption and (self-) expression spread, while indulgence and therapies are sold as personalized rewards - (by-)products that fuel the capitalism circuit, sugar-coated in well-deserved “breaks” in the marathonian pursuit for eternal growth. Such forms of care that lack recognition of humans’ social and relational needs do not stand in the face of collective crises. Care is committed to the flourishing and growth of individuals, yet should acknowledge our interconnectedness and interdependence (Hamington, 2004). Carework, “just like other types of commons”- especially performed as unpaid or underpaid, flexible labor- has been historically and still is, largely devalued and rendered invisible, “resonating closely with ecological commons insofar as they provide unpaid goods and services that support capital accumulation” (Akbulut, 2017). Enforced global primacy of liberal values such as autonomy, independence, self-determination, and others, has led to a ‘culture of neglect’. Structures exploit differences to exclude, marginalize and dominate (Robinson, 1999)- as we have seen in the recent events related to the intensification of racist, xenophobic, anti-feminist, neoliberal and authoritarian, populist threats. While current tumults have laid bare the bloody consequences of politics and spaces that subordinate processes of care to economic ends, goals of care need not fully oppose profitability (Engster, 2007).

This essay is an exploration of commodified and hierarchical relationships within the commons in Barbados. It examines collective care as negotiated resistance with a context-bound consideration for colonial legacies of structural inequity, and today’s domination of market-led priorities.

RELATIONSHIPS

Barbados is a former British colony in the eastern Caribbean islands. As a Small Island Developing State (SIDS), it is characterized by its dense urban population, limited resources, fragile environment, and unstable revenues due to its dependence on international trade - from imported goods to foreign tourists. Historic inequities from colonisation and slavery resulted in poor housing conditions and an insecure land tenure system (Potter, 1989), evolving into highly skewed and uneven distribution of population and settlements (Potter, 1986). After independence, the Euro-Caribbean minority (5%) still controls the economy, while the Afro-Caribbean Bajans (90%) remain employed in service-related sectors, both public (government) and private (tourism industry).

Known for its luxury enclaves on the Platinum Coast owned by highly mobile global elites, a mature industry of real estate tourism blossoms through transformational processes centered around convenient international mobility systems and neoliberal development nestled in interlocality competition. Affordable for foreign house flippers, the vast majority of households in the country cannot afford even the cheapest properties produced in the formal private sector or even in the public housing sector (McHardy & Donovan, 2016). With one of the largest national debts worldwide, the IMF has imposed strict restructuring measures aiming to reduce the 160% debt-to-GDP ratio to 60% over the past decade. While wealthy White tourists bathed their dogs, raw sewage was leaking onto the streets and life-threatening water shortages were frequent in non-touristic Black neighborhoods. Bajans lost their free access to higher education, and essential public services crumbled. Confrontations between local Bajans and tourists, “who form an ethnic category by themselves”, are seen as racial tension between Blacks and Whites (Valkeners, 2007). The recently launched 12-month Welcome Stamp, which encourages non-nationals earning more than $50,000 annually to reside in Barbados without paying any Income Tax, further disembed Barbadian places and materiality from structures of local governance and territoriality, amplifying existing polarization between races.

For many, service and servitude are interchangeable.

Disappearing Boundaries: Swallowed Lives

Despite governmental set-back requirements for coastal constructions, hotel and luxury home developers have still built closer to the shoreline than advised. Sand disappears, fragmenting the coastline and public access to it. The deeply intertwined feeling of thrill and threat while standing on the constantly eroding, thus fluctuating boundary between life and death mirrors the everyday struggles of those at the margins of our society. On the southern and eastern coasts of Barbados, sargassum invasion has been a concern for many years. Marine animals are deprived of their habitats and nearby, their livelihoods.

Plaza and Esplanade

Multifunctional plazas are lifelines for local communities. Known for its “authentic” cultural heritage tours, Barbados’ second largest town is unsurprisingly among the most walkable cities in the country. Public spaces are greater in number, but their condition is degrading due to a lack of governmental funding for local non tourism-related infrastructures. The Esplanade, once a lively hub in the collective memory of many local performers and citizens, suffers today from neglected maintenance.

Privately Owned Public Space (POPS)

Privately owned public spaces (POPS)commonly intrude on public spaces and exude commercialization and exclusion. High-end hotels exclude local beachgoers and fishermen by roping off swimming areas in front of their properties, using client safety as justification. Restaurants with backyard terraces on the beach are often located in between two public spaces, creating a hefty barrier that goes beyond the price tag.

ERECTING COMMONS

Vacations to cure Westerners from their winter blues are marketed as self-care products. Within the same logic, local Carribean employees are care workers too. With the rising number of foreigners staying longer, their relationships with Bajans could be reimagined through the sharing of commons, connected by a mutual understanding to steward them. Supporting local initiatives is instigating dialogue, caring for the home-away-from-home that takes care of them whenever they need it.

Church: Faith above Race

First Sunday in Lent service. Reverend Beverley Sealy-Knight, a young female Black pastor delivered a Sermon about fasting, temptations, greediness, bad habits. While interpreting Matthew 4:1-11, where Jesus “shows himself to be the ideal Israelite, as he refuses to use his power in self-gratifying ways,” she mentions humans’ relationship with nature, encouraging actions of care, protection and non-wastefulness towards our physical environment. In the service program under the “notices and announcements” section, it is written “we offer a very special welcome to all of our visitors, especially those from overseas.”

Church is the only well-known public place frequently and equally accessed by both locals and tourists. Evangelical churches, many attached to progressive communities, could act as a strong voice for advancing local Bajans’ awareness and participation in shaping the “home” they want, while serving as a platform of education and unity that leverages on the common faith to entice a shared sense of responsibility towards the island.

Collectives: Togetherness is Regeneration

Huge customized branded Eco Rebel bins with regenerated vegetation were found on the roadside with the hashtag Eco Rebel- a local community organization advocating for veg-ware (biobased polymers) as an alternative to single-plastic waste. While giving a second life to neglected physical space, Union Collaborative acts as an incubator and a networking core. By “reactivating underutilized properties and collections of cultural artifacts in the community with arts and culture programming,” (Union Collective, 2020) it has provided many grassroot artists with affordable and safe space for creation during the pandemics.

Front Yard, Back Yard: Food is Home

Food is associated with togetherness, from harvest celebrations to family dinners and food markets, where commercial spaces are first and foremost, social, cultural and political spaces. Home could potentially be the node that ties together sustainable tourism, cultural preservation, agricultural self-sufficiency and public health campaigns against the rising epidemics of diabetes.

While Westerners equate Barbados with the utopia of endless vacation, heliotherapy and restorative care, their escapism from Winter cities could complicate locals’ quest for their well-being. Rethinking current configurations of commons is an invitation to create synergies, reinvent the ways people and systems interact: aren’t commons above all spaces of interactivity and connectivity? Suppressed desires during quarantines heightened our longings for physical contact, and the pandemic accelerated existent trends of sustainable and equitable change (Foster, 2020). I see the ongoing multiplication of civil and civic initiatives as our awakening to the deeply political act of collective care. However, with another Great Recession at our doorstep, when lockdowns end but telework does not, how do we keep citizens and cities engaged in deliberate efforts to “address issues of emergency more as norm than exception” (Sample, 2012)? My intention to discuss local examples of a SIDS, where vulnerabilities and resilience are both amplified within a unique country context, is to underline the strong connections that exist between different global forces. Whether it’s climate change, neoliberalization, or COVID-19, socio-spatial inequities remain anchored in everyday spatial practices through a diversity of human-human and human-nature relationships of exclusion, competition, dependence, and interdependence. In ecology, edge is known as “the zone of highest exchange and diversity - the most important of the system” (Pollack, 2012). To learn from a geographically marginalized island, and to continuously magnify voices from the edge in all of their intersectionality and complexity, is to always hear and consider more than one story and enrich ourselves horizontally. Design and policy interventions must embrace multiple meanings within a single project, and countries must consider caring through commoning as a post-growth, sustainable development program.

How would it feel to replace GDP with an indicator for systemic well-being?

It would probably feel like home.

Sophia FY Chen (MSUP ‘23) holds a BSc in Physical Geography, Urban Studies & Interdisciplinary Life Sciences from McGill University. Her passion for field research stands at the interesection of ecology & geology, where our resilience is deeply rooted. An avid chessplayer and explorer of infinite permutability, her favourite book is Calvino’s Invisible Cities.

12

Re-Defining Capital: Leveraging Social and Ecological Capital for City

Addis Ababa is considered the diplomatic capital of Africa. Today, the city center is going through rapid development with a large influx of people and capital. The government and foreign developers are implementing a generic vision of a ‘modern developed city’. Although perceived as progressive, this development is in fact fragmenting the city, destroying ecosystems, and widening socioeconomic gaps.

Foreign investments extract capital from the city rather than benefiting the locals. The city prioritizes developers that bring in investment for high-end projects, which inturn encourages gentrification. Instead of investing capital in housing and infrastructure to support local communities, this development displaces the Kebele (low income housing) residents and disrupts social networks. This process increases real estate value in the city center, thereby forcing low income communities to migrate to the condominium housing built on the outskirts of the city. This shift leads to breaking of social networks, loss of job opportunities and isolation from the city’s economic center. The change from informal, community oriented Kabele housing to the generic high-rise, high-density typologies impact social interaction and culture. In addition, the river lacks connectivity to the city fabric and suffers from ecological degradation that will worsen with the concreting of its banks.

Today, monofunctional systems dominate developing countries and high-end real estate projects receive the most capital. These imported ideologies of development fail to address the current spatial and social challenges of Addis Ababa. Multifunctional capital systems promoting a more progressive and participatory approach to urban challenges may reverse the current practices driven by real estate interests. The project not only looks at addressing urban challenges through design but also delves into how we can mobilise and maintain cohesive collations among communities and agencies to build stronger social capital. Taking advantage of the banks and global actors in the city center, the project can be realized through private-public partnership. The Edir and the Equb are existing social cooperatives that serve as social nets for the community. Multiple Edirs could come together to combine a bottom-up and top-down approach to implement and take ownership of the design.We envision the implementation of this project through multiplicity of interventions rather than a masterplan.

The new development in the city center pressures displacement of Kebele residents. The design will empower residents with flood-mitigating ecological infrastructure, such as stormwater collection and reuse systems, decentralized waste stabilization and retention ponds. The social infrastructure will support financial empowerment, education, training center, health and recreation. The community organization will mediate incremental housing, which will be funded as part of the private investments that come into the city center. The incremental housing will evolve vertically, saving 50% of the coverage area for future densification.

The Filwoha hot springs form the ecological center of the city. A series of constructed wetlands and restored riparian vegetation will clean the River, retain flood water and allow biodiversity to thrive. This ecological infrastructure will grow to include the commercial areas, thereby empowering local custodians to maintain the river. Inclusive recreational spaces and walking trails will improve accessibility, and the bath will create a public space.

Meskel square is one of the most resilient public spaces in Addis Ababa, yet there is lack of connectivity to the River due to massive car centric transportation infrastructure. The vacant lot on the river edge will facilitate religious functions, daily leisure activities, local trade and river cleaning mechanisms like floating trash collectors. Through cleaning, the community will earn social capital credits, which can be exchanged later for services. Further, pedestrian connectivity to the River edge will be improved through a road diet. Gradually the public institutions will network to form a flexible public realm.

The city center supports multiple daily activities and annual celebrations. Hence, resiliency, flexibility and adaptivity are central to the design.

This project was designed as a part of the Graduate program at Columbia University, GSAPP, 2020.

We are a team of graduates from the Masters of Science in Architecture and Urban Design (MSAUD) program at Columbia GSAPP and we are currently engaged in research and urban design projects of varying scales and contexts in esteemed public and private sector organizations. As an international group of designers from India, Israel and Saudi Arabia, “Redefining Capital” instigated rich discussion and a fruitful collaboration exploring the urban paradigm shift through the lens of social and ecological capital.

13

Letter & Plan

The GSAPP UP ACTION: LETTER & PLAN – one of ten letters that called for institutional change at GSAPP in the summer of 2020 – was published and disseminated to GSAPP Administration on July 10, 2020. Over 30 current, incoming, and graduated students of the Masters and PhD Urban Planning program contributed to the publication, demanding GSAPP to abolish its racist foundations and rebuild an equitable and inclusive professional school. The swell of frustration and urgency to organize followed the lack of support and communication from GSAPP Administration during the COVID-19 pandemic that halted in-person classes in March 2020. GSAPP also demonstrated a lack of awareness, commitment, and action to undo the anti-Blackness within the school’s curriculum and pedagogy, student recruitment and faculty hiring processes, and general school culture. This was sorely felt since the reignition of the Black Lives Matter movement after the police murdered George Floyd in May 2020. In addition, the Trump Administration in July 2020 threatened the safety and security of international students in the United States, furthering frustrations as students waited for support from GSAPP. Re-publishing this letter in URBAN Magazine documents and preserves a small piece of the student-led activism that occurred at GSAPP in the wake of nationwide civil unrest during a pivotal moment in the ongoing fight to end racism.

Since the letter’s publishing, almost 100 UP affiliates have added their signatures in support. The UP Action Group has held multiple student-led workshops, open town halls, and meetings with UP faculty and administration, using the plan as a base for discussion and as inspiration for new ideas. The UP Action Group has also worked to develop student-led networks of mutual aid, including the UP Emergency Fund and a growing repository of online resources to help students navigate confusing, unfamiliar or intimidating systems at Columbia and across New York.

This work has served as a model for a number of other GSAPP programs to call for change, inspiring students in Historic Preservation and Architecture to organize and write action plans for their respective programs. The UP Action Group has since joined and become active members of a larger coalition of GSAPP student organizations. The GSAPP Student Advocacy Coalition harnesses the momentum of program Action Groups, BSA+GSAPP, LatinGSAPP, QSAPP, Program Council, and others to push for change in GSAPP student governance, demanding more transparency and accountability at the administrative level.

As written in the letter, “we cannot move towards an anti-racist planning profession focused on equity and social justice without achieving it within our own program and school.” Even with the encouraging progress made to date, this work is just the beginning. We hope that the publication of this letter can inspire future classes to carry this work forward, build on our demands, and continue to strive towards realizing a more inclusive, equitable, and anti-racist urban planning education.

7/10/2020

Dear Dean Amale Andraos,

Director Weiping Wu,

UP Program Faculty, and

GSAPP Administration,

cc: onthefutilityoflistening@gmail.com

gsappblackfaculty@gmail.com

In the past few months, the murders of George Floyd, Tony McDade, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, and countless other Black people have fueled a national reckoning with the anti-Black racism and white supremacy at the core of this nation and its institutions. Throughout this reckoning, it has become abundantly clear that awareness and acknowledgment of systemic inequities are not enough. Changing the systems that continually oppress along race, class, and gender lines requires action that undoes, reimagines, and reconstructs these systems.

With this in mind, a group of incoming, current, and recently graduated Urban Planning (UP) students in Columbia’s Graduate School of Architecture, Planning, and Preservation (GSAPP), formed with the understanding that a just and equitable future requires looking critically at how the institution that brought us all together—GSAPP—perpetuates these very systems of oppression. The UP Program repeatedly emphasizes the “importance of advocating for social justice through planning” and claims to pay “special attention to…the quest for social justice.” But in order to claim a “quest for social justice,” we must first reflect critically, honestly, and humbly on whether the UP Program has fulfilled this commitment. In reflecting, we have reckoned with the ways that programs across GSAPP, including the UP Program, falls short of these goals, and we have also identified immediate actions and processes that the UP Program, with the collective support of its students, faculty, and administration, can enact to genuinely accelerate progress towards social justice, as the program promises.

We recognize that this work must center and amplify Black voices in the GSAPP community. First and foremost, we stand in solidarity with the Black Student Alliance (BSA+GSAPP) and fully support the powerful reflections and demands articulated in their recently published statement, “On the Futility of Listening.” As BSA+GSAPP states: