“Anyone who can solve the problems of water will be worthy of two Nobel prizes—one for peace and one for science.”

– President John F. Kennedy, 1962

Studio participants

Volta Redonda

FOREWORD

When A River Crosses Frontiers

Paraíba do Sul River gives its name and meaning to an extensive valley in Brazilian lands. It crosses three main states of the country—São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro and Minas Gerais being responsible for water supply, energy generation and water resource to social and economic activities that are carried out along its course.

It has been considered a strategic river in the last decades, in which water crisis has been discussed, especially due to the importance given to water provision in the Rio de Janeiro metropolitan region, from which Paraíba do Sul River represents an important supplier.

The recovery of its waters, the protection of its wetlands and tributaries, the consciousness, the valuation and the appropriation of its notable landscape, together with the valley’s residents, constitute themselves, however, as hard tasks to social actors involved direct or indirectly with the river: administrators, managers, users, researchers, residents and visitors.

The importance of Paraíba do Sul Valley to the Brazilian culture and economy is centenary. The extensive Valley made of varied regional shades, sheltered coffee plantations in the 19th Century, the industrialization in the 20th century, besides the country’s main economies fostering agricultural and rural development, structuring itself as a linking axis among its biggest metropolitan areas: São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro.

In the 21st Century, new perspectives need to be outlined to what is called “extended metropolitan region” which is formed by the Valley’s succession of cities, added to approaches to a fairer social and environmental responsible economic development. There are demands and passives of all nature: environmental and urban planning; managerial and political-administrative; from social and cultural nature. Above all, there is a difficulty in regional integration and also of understanding peculiarities and features of this place—the Paraíba Valley.

In the last 15 (fifteen) years, cities from the Mid-Paraíba Fluminense Valley, one of its specific sub-regions, and the Paraíba do Sul River itself have been objects of my research investigations. Being an architect and urban planner and also living in the region, I developed my Master’s dissertation and my doctoral thesis at the Post-graduate Program in Urbanism of the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (PROURB/UFRJ), on themes that focused on the valuing of significant aspects of some cities along the valley: their cultural and built heritage as well as the presence of the natural features and landscape of considerable beauty.

The thesis entitled Paraíba do Sul: one river, four cities, a socio-environmental heritage at stake, carried out between 2010 and 2014, had as its main goal to reveal some strategic ways that could enable a more respectful and approximated human approach to this river, in Resende, Barra Mansa, Volta Redonda and Barra do Piraí.

The thesis is based on analyses and proposals of diverse dimensions, such as environmental and urban history of the region, the legal framework, water and city management, contemporary intervention perspectives and their feasibility within the regional reality. Since its publication, the thesis has been used as a contribution for a critical thinking about the river in the Mid-Paraíba Valley trying to reach in this process, the largest possible number of social actors.

Documental analyses and miscellaneous prospection have confirmed the original hypothesis of the thesis that the Paraíba do Sul River is a still questionable social and environmental heritage, due to delays in terms of protection, conservation and enhancement actions in its history.

The partnership between Columbia University Urban Design and UFRJ directly involved my research and my current institution in Volta Redonda – Centro Universitário Geraldo Di Biase (UGB). It reinforced the relevance and the growing centrality that the Paraiba do Sul River and its water issues, could achieve.

We co-organized a workshop that took place January 8-15, 2016 on Water Urbanism focused on urban design in some of the cities crossed by the Paraíba do Sul River, the same studied in my doctoral thesis.

The workshop had the participation of university teachers, undergraduate and graduate students in architecture and urbanism from UGB associated to faculty and students from PROURB-UFRJ and from the Urban Design Program of Columbia University, in New York. Beyond the academic interest, the participation of UGB through its Program in Architecture and Urbanism—a traditional and well-known institution in the studied region, was essential to the work developed as the assumption was to produce useful proposals founded in the local and regional reality.

The organized activities aimed at developing preliminary urban intervention proposals oriented towards the water crisis issue, which currently affects not only the municipalities of the Mid-Paraíba Valley, but also the water supply of Rio de Janeiro’s Metropolitan Region itself. It included a trip to the Region with the purpose of studying the intervention areas, as well as establishing contact with different local actors.

Besides the great joy of seeing my thesis being interpreted and applied in such a responsible and inspiring way, UGB professors and students felt proud in participating in this event and in narrowing contact established by students who have distinct and diverse nationalities and cultural backgrounds. Furthermore, there have been data and digital files accumulation acquired about the Paraíba Fluminense Valley. In this way, the workshop stated the importance of widening academic and scientific borders both to the teaching staff and to the students, due to two academic and scientific centers of excellence at both national and international levels.

The closing workshop and the preliminary proposals presentation happened at Studio X, in Rio de Janeiro, on January 14 and 15, 2016 and were then further developed during the Spring semester of the Urban Design studio of Columbia University.

At the conclusion of the studio, in New York, in April 2016, all felt that the work opened the doors to an up-to-date and more systemic organization among technical, academic, administrative and social institutions within the Mid-Paraíba Valley region and beyond. The diagnostic syntheses, followed by strategic indications to the studied cities and their connections, will be of great value to the Valley managers and residents. They will be able to find themselves strengthened in the network under the insight of scholars and specialists in predicting opportunities of using urban territories all over the world in a more responsible and sustainable way.

INTRODUCTION

Water Urbanism

Water Urbanism is an innovative approach to design practice and pedagogy that holistically joins the study of social and physical infrastructures, public health, and hydrological systems. It challenges conventional planning practices that isolate elements of an urban system and instead starts with the assumption of a joint built and natural environment within which humans and machines operate. These complex, interrelated issues require a design-driven, integrative, and systems-based approach, one grounded in a deep understanding of social life, political context, and spatial thinking.

Water Urbanism posits that water and cities must be understood within an expanded notion of a constructed ecosystem. These systems- including rainfall, water retention, water harvesting, industry and agriculture use, re-collection and re-cycling, culture, water access and sewage, are framed as opportunities within an urbanized ecology with the potential for design interventions along multiple points in the cycle. Water Urbanism also implies a set of design practices that engage people with policy and to continuously manage the urban eco-system to promote resilient communities and participatory practices. The spring semester 2016 Urban Design studio investigated these urbanization challenges in two regions with robust ecological contexts and development trajectories: the Vaigai River valley in Madurai, India and the Paraíba Valley in Brazil.

Paraíba Valley, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

The lack of regional cooperation between Rio and Sao Paulo, and water contamination of the Rio Paraiba and related waterways has created a public health crisis for the region’s poorest inhabitants.

The Paraíba Valley extends between the two largest cities in Brazil, Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo. The valley is crossed by a national highway serving a series of regional centers and medium-sized cities which are forming continuous conurbations in several spots along the corridor. This phenomenon has been associated with the formation of the first macro-metropolis of the southern hemisphere: the so-called ‘Brazilian megalopolis’ that includes the metropolitan areas of São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro but also the entire corridor. The strategic aspect of the valley is directly related to the water flowing through the Paraiba River. Cities located on its immediate banks are dependent upon its waters, and above all, 10 million people living in the metropolitan area of Rio de Janeiro are intimately dependent on it: 80% of all drinking water consumed in the second largest city in the country comes from the Paraíba watershed. In addition, the same water is also an important source of energy due to a complex infrastructure of dams and pumping stations created to overcome the mountain ridge of Serra do Mar. The massive water is collected in the Paraíba River and is transposed from one watershed to another, feeding a series of reservoirs equipped with hydroelectric plants, reversing the course of rivers and even creating an entirely artificial water body: the Guandu River, the main source of water supply in the metropolitan region of Rio de Janeiro. The fact that Rio is highly dependent on the Paraíba River and its watershed explains the conflict of interests that has developed between the opportunity of economic intensification of a region whose connectivity with the neighboring fast developing areas of São Paulo gives the region a great potential for development and, at the same time, the need for environmental protection and remediation of the Paraiba River watershed, which is essential for the conservation of its natural resources (water and energy) on which ultimately depends the economic growth itself. Faced with such a situation, the 2016 Columbia Urban Design studio is investigating the ongoing process of urbanization along the valley, the regional interdependencies of resource extraction and consumption, climate and deforestation, settlement pattern and migration relative to emerging spatial forms along the river corridor. Design teams are moving beyond notions of city vs. countryside to describe interdependent systems that comprise the larger territory and advance a holistic approach of urban life that is inclusive of social and natural systems. The studio is focusing on water as a lens through which to discover, investigate, and transform this condition. Water is a central theme, and a study of the rapidly urbanizing Paraiba valley itself reveals both the political conflict and regenerative potential of water as an urban catalyst. By adopting an integrated design methodology, students move beyond traditional questions of density and built form to consider public health, access, food, waste, ecology and energy as key urban questions.

Columbia Faculty: Kate Orff (Coordinator) Ziad Jamaleddine, Petra Kempf, Laura Kurgan, Guilherme Lassance, Geeta Mehta

Collaborators & Friends of the studio include:

- Centro Universitario Geraldo di Biase (UGB) in Volta Redonda

- Universidade Federal Do Rio De Janeiro Faculdade De Arquitetura E Urbanismo

- Studio X Rio

Andréa Auad Moreira, Ph.D. in Urbanism (PROURB/UFRJ), Professor and Coordination Supporting Staff of the Architecture and Urbanism Graduation Course, Coordinator of the Graduate Program Course in A&U: Theories and Contemporary Practice at UGB.

UGB Teaching Staff:

UGB Undergraduate Students:

Letícia Araújo, Mario Robson Duarte, Rafael Dias, Vinicius Duarte

1

Urban Portraits

Expanded metropolis: a highly strategic region

A regional challenge: how to combine economic development with the conservation of natural resources

Paraíba do Sul River: a major water resource for Rio de Janeiro

The industrial decline: what are the prospects for the future?

The need for environmental remediation: how to reinvent the regional economy?

Existing infrastructure: what opportunities are there to repurpose existing infrastructure?

Water pollution: can we rethink the water system as a regional asset?

Informality: can we deal with land-use complex challenges?

Social housing: what are alternatives to existing programs?

Vacant lands: how to make them productive?

2

Maps

3

Group Projects

4

First In Line

Students: Hannah Beall, Nicki Gitlin, Eleni Gklinou, Grace Salisbury Mills

What if reclaiming the fallow, linear infrastructure of the Mid-Paraíba valley spurred a re-centering of its urban structure and culture?

A regional toolkit, you say? But what are the tools!? How do you use them? And isn’t linear re-centering a paradox anyway?! ‘First in Line‘ provides a framework: the ‘first’ trigger of a regional linear urbanism that responds to the critical challenges facing the Mid-Paraíba Valley. Capitalizing on residual rail infrastructure, a regional network of programs and spaces is created through a ‘toolkit’ of flatbed modules. This toolkit is local, tactile, and context-specific, yet forms an open-ended system that can trigger an array of socio-spatial, economic, and ecological possibilities at a regional scale. Through the re-claiming of its forgotten infrastructure, the Mid-Paraíba may break free from the shackles of its industrial past, towards an alternative regional identity.

The Mid-Paraíba faces three complex and interrelated challenges: first, the state of post-industrial paralysis that is reinforced by the struggle of once-fundamental industries to re-establish their role; second, the absurd political divisions which disincentivize collaboration and have produced an unsustainable process of urban dispersal; and third, the vast environmental devastation: especially including the connected issues of deforestation and water pollution.

Yet, the region also possesses a highly unique asset: a vacant, linear right of way, owned by a company (CSN) whose role in the region is begging for re-invention, and passing—by virtue of its industrial origins—through the entire region: crossing an endless variety of spaces and sites. Can this potentially connective device be activated, both at a regional and local scale? How could the region be re-centered around this linear piece of history?

Fortunately, the ingredients already exist: there are locally manufactured flatbeds, and a disused rail running along the right of way—an easy way to inhabit the line. More importantly, there is a diverse array of parties with a vested interest in building a regional network of programs and spaces: cultural venues, reforestry labs, micro-commerce hubs, educational facilities, public spaces, to name only a few.

It all seems fairly simple. Starting small at first, a network of programmed flatbed modules, could transform the right of way into a regional metabolic corridor. At once local and regional, mobile yet context-specific, the network of spaces, programs and needs created could offer endless possibilities for connections, catalyze new economies, foster new social dynamics and allow boundaries to be crossed.

With the small-scale concentration of people, density and programs, the region could gradually be re-centered around this line, allowing the impact of this corridor to extend beyond its immediate surroundings. The expansive vacancies which have long trapped the region in its paralyzed state could be re-injected with a new value, a new centrality, and new potential to propel the region into its next epoch. As the owners of this opportunistic urban layer, CSN and other industries would have a chance to re-establish themselves as regional figures. In addition, this re-centering could trigger new zoning types, encourage urban afforestation strategies: providing an alternative to the current trend of dispersed, disconnected and environmentally-devastating urbanism.

By virtue of its incremental, evolving nature, this system is open-ended: on the one hand, the network of flatbeds may become a permanent part of the regional fabric; on the other, it may trigger yet another phase of the ‘right of way’ as a connective regional corridor (such as a light rail system). Either way, the re-claiming of this linear armature provides a mechanism for enhanced regional collaboration and a strengthened identity of the Mid-Paraíba between the megacities of Rio and São Paulo.

By capitalizing on this fallow yet highly unique dispersed linear site, there is a chance to re-think the way ‘urbanism’ is done in a stagnant, post-industrial setting that is by no means an isolated circumstance. In the context of Brazil’s current political turmoil and threatened industrial economy, this strangely implementable toolkit presents one ‘line’ of thinking forward.

A politically fractured region

A linear network of connective infrastructure

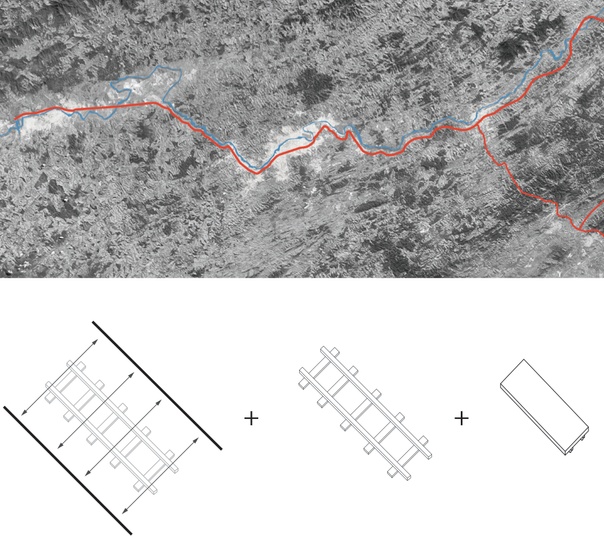

A Linear Opportunity

As a result of privatization, a vacant linear right-of-way passes through the Mid-Paraíba region. Crossing and overlapping with a variety of spaces and sites (overpasses, underpasses, vacant land, pedestrian pathways and the Paraíba do Sul river) the right-of-way presents a rare opportunity for local and regional intervention, simultaneously.

Recurring Conditions of Overlapping Infrastructure

Right of way + Rail Line + Flatbed Car

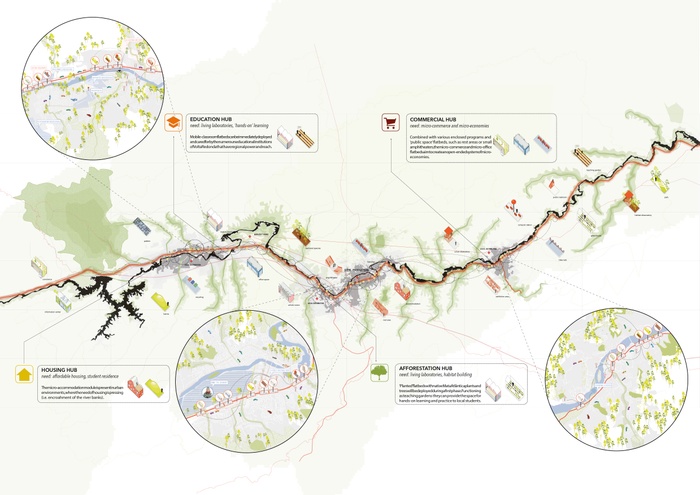

A Regional Toolkit

The “regional toolkit” consists of flatbed modules which reflect regional demands: micro-commerce; local reforestation labs; public amenities and mobile education units. Together, these modules form a regional network of programs, spaces and needs that can be implemented along the right-of -way, giving it a new connective role and sparking the re-use of vacant land.

A range of program options

Sample pairing of two units

Design Methodology

The Paraíba do Sul Regional Alliance comprises a diverse array of parties with a vested interest in building a regional network of programs and spaces: cultural venues, reforestry labs, micro-commerce hubs, educational facilities, public spaces, to name only a few.

Flatbed modules are manufactured locally, through the collaboration of numerous related industries that participate in different steps of the process, and with CSN holding a central role. The deployment happens in a need-based manner, in collaboration with multiple stakeholders ranging from local institutions, to municipal governments and local communities.

With the potential of a light rail line eventually occupying the right of way, the flatbed modules are designed to have a ‘second’ use. As triggers and phases evolve, and the new rail is constructed, they can be gradually redistributed throughout the region, as needs arise.

Design Methodology

Implementation and Stakeholders

Sample Regional Deployment

Time-based Evolution

A dialogue between the new mobile programs and the existing regional urban fabric emerges and expands over time. The reintegration of the right of way into the urban realm creates a linear anchoring armature, engaging communities, local institutions, adjacent infrastructures and establishing local and regional continuity.

Deployment, Evolution, and Future

As this open-ended framework is designed to enable a larger regional transformation, continuity and re-centering, its impacts at a city and regional scale are ever-evolving. As the right-of-way is rendered more accessible in the public’s eyes through active and early-on engagement, each phase triggers the next; flatbeds gradually occupy the right-of-way; transverse connections are formed, while adjacent, unproductive land that has long laid vacant is temporarily activate by local communities and stakeholders,revealing its potential; and programmatic ‘links’, such as extensions of existing educational institutions are anchored on the right-of-way, underlining the opportunities for connectivity in the urban centers and the region.

As reorientation along the line proceeds, uses aggregate on and around the right-of-way. The introduction of a new ‘Right-of-Way’ zone supports densification that connects the urban centers, rather than permitting an unplanned urbanism to take over and lead to dispersed, impromptu territories. Change in land uses continues with the gradual absorption of adjacent, unused spaces into the right-of way, consolidating the line as a regional center; a connective device that may spur new opportunities, such as a regional light rail system.

Deployment

Evolution and Future

Revealing Potential

From raising awareness about the right-of-way, to becoming useful tools for revealing potential new uses and triggering new activities, the flexibility of the modules is their most important characteristic: they reveal and attract attention to spaces within the region that people normally wouldn’t take a second glance at or inhabit.

The integrated right of way becomes a contiguous part of the urban fabric, changing spaces previously untouched and fostering active program: central locations can lend themselves to creating gathering spaces,giving the right of way a level of significance to residents, rather than being a fallow landscape.

Beacon

Raising Awareness

Overlook

Right-of-Way Festival

A Gradual Transformation

Visual installations initiate the activation of the right of way, reintroducing a forgotten infrastructure as a part of the region. When the flatbeds are installed, their presence attracts attention to the right of way, absorbing and reflecting the adjacent landscape. Eventually, as the right of way is transformed, it may continue to evolve and become something else. One possible version of this future is a regional light rail system which would further link the cities along the Mid-Paraíba Valley.

Signage

Urban Afforestation

Evolution to light rail

5

Collective Waterscapes

Students: Guangyue Cao, YanShun Lee, Nishant Mehta, Ziyang Zeng

What if the urban landscapes along the Paraíba River filtered stormwater and wastewater, with micro-infrastructure embedded into the fabric of public space?

‘Collective Waterscapes’ envisions Paraíba Valley cities as unified partners for improving the water and health quality of the greater region of Minas Gerais, São Paulo, and Rio de Janeiro. To address the region’s pressing water issues, this proposal establishes a landscape framework for future waste water management by maneuvering surfaces and implementing simple place-making strategies driven by water-based programs. We believe that access to clean drinking water is not only a daily necessity, but an asset which will become the driving force for a healthy and resilient environment. By providing local actors with the tools and techniques to implement waste water treatment micro-infrastructures into the city fabric, a new urbanity of culture and living will emerge from the water systems that sustain it.

Due to a lack of policy coordination between jurisdictions and challenges implementing waste water treatment infrastructure, residents who depend on the water of the Paraíba River also contribute highly to the pollution, which results in an unhealthy and unsustainable cyclical relationship with the river. Our proposal aims to reverse this disconnected and unhealthy relationship. The resources currently concentrated at the Guandu Treatment Plant will be redistributed and deployed across the region as a series of micro-infrastructures.

Currently, AVEGAP, an interstate committee of the hydrographic basin of Paraíba do Sul river, manages the river basin, which stretches across three states- São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro and Minas Gerais. Our approach proposes AGEVAP as the primary agent to direct small scale waste water treatment interventions in coordination with local governments, organizations and residents, while enforcing them through policies.

By analyzing the current water jurisdiction, our proposal informs how and whom with AGEVAP can intervene at different scales within the current framework, including the water basin, mid-Paraíba, district, urban and clusters scales.

Nested scales of water urbanism

Regional water network

Pollution in the region

According to World Health Organization (WHO), the headwaters of the Paraíba River are highly contaminated. Toxic bacteria in the water level are at least 25 times greater than WHO standard. Despite the poor water quality, six million people living in the river basin, including the eight million residents of the Rio metropolitan region, depend on Paraíba do Sul for potable water.

Our thesis

Instead of centralizing resources on mono program and large infrastructure, what if we distribute waste water micro-infrastructure into the urban fabric as public spaces, through policies and a shared sense of responsibility?

Our proposal is a future water management framework for AGEVAP to insert itself within the current jurisdictions and collaborate with stakeholders at various scales.

Scales of AGEVAP zones

At each scale, we identified the challenges and level of participation for AGEVAP to develop an integrated urban design framework for future water oriented management and development.

In conjunction with the United Nations Millennium Development Goals , Brazil has committed to cut the number of people who don’t have access to proper sanitation and clean water by half. The project ended in 2015 without any major improvements. However, within United Nations’ newly published water sanitation goals , those most applicable to Brazil are set for 2030:

- Achieve universal and equitable access to safe and affordable drinking water for all.

- Implement integrated water resources management system.

- Strengthen the participation of local communities.

Scales of cleaning water

Part of this framework is to negotiate the local landscape, and the culture and socio-economic dynamics that come with it. To implement this vision we focused our design on the creation of new urban centralities through the synergies between water infrastructure and socio-economic spaces. Driven by the design principle of manipulating surfaces and landform to make the processes of water more visceral and visible, a series of spatial typologies are grafted onto water infrastructures to create social and recreational spaces. Most importantly, these considerations will become “locally rooted” through decision making and participation at the community and municipal scale, allowing residents to foster a healthy relationship with the river.

With this approach, we envision AGEVAP to spearhead these scales of water cleaning interventions, not only to achieve national health goals, but to also re-imagine the region as a series of united cities that clean the river to attract new industries and economies. Embedded within a restored ecology generating a healthy relationship between the cities and the river.

Combing all scales of water infrastructures, this proposal is a showcase of the variety of scenarios of hybridizing water infrastructures and public spaces along a prototypical tributary. Replicating this along the Paraíba, the collective effort of cities can capture, reuse and clean water before it flows into the Paraíba do Sul, contributing to a healthier water ecology for the larger region.

Sample tributary neighborhood

A new urban section

S: Community space

S: Community space

S: Community space

M: Neighborhood node

M: Neighborhood node

M: Neighborhood node

L: River edge park

L: River edge park

L: River edge park

6

Tactical Infrastructure

Students: Dhruv Batra, Serena Fernandes, Ashwini Karanth, Shiwani Pol

What if shared infrastructure sparked housing densification and the improvement of residual spaces?

‘Tactical Infrastructure’ addresses the vulnerable ecological system of the Paraíba River Valley by introducing densification as a tool to carefully orchestrate new social housing typologies to the inner city centers in the Paraíba Valley. As informal housing is being relocated from the polluted riverbanks to these new social housing typologies, this project aims to relieve both the environmental pressure towards the river and breaks away from the rigid social housing Program “Minha Casa Minha Vida” (MCMV) run by the Federal Government.

The Paraíba Valley faces great challenges due to pollution, creating hazardous conditions to the ecology and the habitants living close to the river’s edge. In addition, the informal settlements located along the river are most susceptible to damage during flooding.

The Brazilian social housing program (MCMV) provides these inhabitants housing outside the city center, far away from commerce and public infrastructure networks, creating unsustainable and disconnected urban conditions. The pre-fabricated mass produced cookie cutter housing typology lacks a sense of place and more individual expression. Moreover, these highly standardized projects have severe environmental impacts as they are not able to adapt to the existing complex topography that has to be hugely transformed.

This project utilizes the vacancy in Volta Redonda as a testing ground for a different approach. This proves to be an opportunity for ‘Tactical Infrastructure’ to take shape. Utilizing the existing efficient policy of the MCMV, the project proposes the introduction of a land bank that assists in implementation of strategies at a local scale.

A proposal to densify existing city fabric is foreseen to increase urban adjacencies for residents living within newly proposed housing settlements. Utilization of vacancies will increase the economic value of the land that is currently depreciating. Introduction of multiple uses will ensure diversity in activities within existing neighborhoods to allow employment, entrepreneurship and community development opportunities. Diversification in the use of built environment that revolves around the public realm will increase the prospects for shared public spaces to co-exist within dense housing environments.

Steel is used as the main building material in all design iterations. The use of steel is advantageous in two aspects. It ensures that the informal expansion of housing units is curbed thanks to the fact that steel construction needs skilled labor. It also provides grounds for CSN to become a stakeholder on shaping the image of the ‘city of steel’ from an area with vacancies and pollution to a city with a more vibrant life and intense activity, thus becoming an example for the rest of the cities in the Paraíba Valley.

With the success of this project, there will no longer be a need for the housing programs to be developed at secluded enclaves outside the city hence ensuring social equity within the existing fabric, and a vibrant mix of public spaces and landscapes.

Infill over vacant buildings

Volta Redonda

The project focuses on the city of Volta Redonda, which is characterized by high levels of both air and river water pollution as well as occasional flooding. Due to the automation of the steel production process in the plant of CSN and also the competition with other companies, growing rates of unemployment renders high levels of building vacancies within the existing city fabric. At the same time self-built houses have been hampering the environment and ecology.

The MCMV Program that provides housing to these vulnerable people has been producing housing developments that are totally disconnected from the city fabric and employment opportunities.

The vacancies in the cities vary in scales, from units scale to large vacant parcels. The project focuses on individual unit vacancies and intermediate vacant land parcels at the neighborhood block scale.

Vacancies in Volta Redonda

Vacancy map in Volta Redonda

A new procedure

The process that Brazilian government follows in order to establish a new MCMV development involves three main stakeholders: the Caixa Economica Federal or CAIXA Bank, the Ministry of Cities and housing co-operation. In our proposal, new stakeholders working in collaboration with CAIXA Bank will now be National Secretary of Accessibility and Urban Programs (SNAPU), National Department of Transport and Mobility (SEMOB), National Environment Sanitation Secretariat (SNSA) and other ministries involved with urban issues to oversee the implementation process.

Proposed MCMV++ Procedure

Proposed MCMV++ selection procedure

Staircase as social space

CSN as stakeholder

On site plug-in

These prototypes vary in scales and functions depending on where they are located, for example in this splice of the city, we see various urban conditions. At the river’s edge the linear structure becomes a prototype replicable at the urban and regional scale, over the railway tracks it becomes a pedestrian foot-bridge. All while incorporating small scale commercial activities, recreational spaces, cultural spaces and community level infrastructure.

At moments the vertical infrastructure is set up in vacant singular land patches to incorporate future improved MCMV we are calling MCMV++. These developments also incorporate small scale commercial activities at the street level and open up the staircase to community interactions.

Infrastructure as connection

Infrastructure transforming neighborhood

Linear Strip

Tactical micro to macro scale infrastructure is first plugged in on site through two main interventions: the linear horizontal and the vertical structures. The project begins with the implementation of a ‘linear horizontal strip.’

Operating on a macro scale, the intervention is a hybrid between a highly functional water treatment unit and a public space. The prototypes designed at a conceptual level vary in scales and functions depending on their adjacencies within city centers.

Infill strategies

River edge prototype

Linear Prototype

Vertical Intervention

The ‘vertical’ structure essentially contains various components that provide adequate connection to existing public infrastructure of the city.

It incorporates spaces to recycle organic waste, gives the opportunity to harvest rain water and solar energy while also providing social spaces, shaded areas and Internet connectivity for the residents.

Vertical intervention

Strategies of implementation

Sample site: Tactical Infrastructure triggers neighborhood revitalization

7

Paraíba Riverscape

Students: Jiajing Cao, Surbhi Kamboj, Yi-Yen Wang, Xinye Li

What if the Paraíba Riverscape is re-imagined to form a relationship between people and the river?

‘Paraíba Riverscape’ is a framework designed to reinterpret and combine environmental codes and regulations with social programs, by intervening along the Paraíba Riverscape. The interventions are aimed at forming a relationship between the people with the river.

The Paraíba River has been a lifeline of economic and urban development for cities around its basin. Due to the pollution of the river because of massive urbanization and industrialization, the ecology of the Paraíba Valley is no longer in equilibrium. To restore ecological balance, the forest code by the federal government prescribes permanent protected areas as a 50 -200 meters uniformed riparian edge along the river depending on its width. However, this linear riparian edge disregards the existing spatial context within the built and unbuilt areas. Our framework reinterprets the linear riparian edge condition to form large ecological zones in both unbuilt areas of the river and in built areas such as in cities. The river edge is stretched and incorporated in the existing context to create Ecological Riverscapes and Cultural Riverscapes [Figure 1].

This newly introduced framework can be applied all along the valley scale, respecting the spatial conditions, forming experiential and programmatic strategies to enrich the ecology, culture and habitat in the valley. Two pilot sites have been chosen to initiate and test the strategy for incorporating the riparian edge interpretation to create Ecological Riverscape in the unbuilt area and Cultural Riverscape within the urban fabric [Figure 2].

By means of creating community stewardship through Green Capital Credits, the developed strategy also aims to engage the local people in the transformation of Paraíba Riverscape, A system of Green Capital Credits has been created, because of which people are encouraged to participate in activities which in turn can be redeeming through an earning menu. The capital credits are rewarded by the basin integration agency of Paraíba River (CEIVAP), which benefits from stakeholders such as industries and local businesses. CEIPAV, hence, becomes a middle man by directing the environment redemption fees towards the community engagement program to sustain the framework [Figure 3]. Hence, Paraíba Riverscape framework becomes a means of manifesting culturally and ecologically rich habitat across the river valley connecting river to the people and people to the river.

Project Framework

Paraíba Riverscape

Valley Scale Toolbox

For the strategy to be implemented all across the valley, the project proposes three types of unit strategies namely, riparian edge, access, and activity units.

The riparian zone provides a guideline to apportion the riparian edge into three zones; marsh zone, shrub zone and upland zone. Together, they form a strengthened and softened riparian edge which mitigates the flood, stabilizes soil, traps sediments provides the habit for aquatic species along the water edge.

The access units propose multiple access option at different levels like walkways, wooded trail, steps and floating deck on the surface of the water, for the people to access the river and create a democratic space for recreation.

The activity unit is a light weight temporary unit which can be combined or reconfigured to serve as bus stops, vendor units and picnic space and so on. The units are designed such that people can adapt them depending on their needs and space availability whether in urban nodes, river bank or forested areas.

Riparian Edge

Access

Activity Units

Ecological Riverscape

A pilot for the Ecological Riverscape is conceptualized in a location outside of the urban fabric, in between the cities of Resende and Barra Mansa. The meander shape of the river in this location allows it to be stretched to form a thicker ecological zone.

Partnering with the industries next door, and rebranding its Ecological image, the site pilots an interactive water cleaning park. The industrial waste water is captured and channeled to pass through sedimentation ponds, aerobic ponds, and then a series of surface wetlands to process the water to be reused. As part of the process, the local people experience the water cleaning process by means of school field trips, educational programs and workshops.

In conjunction with this park, the fallow land next to the industry is transformed into an ecologically rich biodiversity zone by diverting the water into multiple channels from upstream to downstream. The water passes over the wetlands mitigating the flood, trapping sediments, improve the water quality naturally, and as a result, would create multilayered biodiversity.

The park will serve as a gateway for the people from the surrounding cities as they may use the park for hiking, camping, picnicking, and birdwatching. Through a process of reconfiguration and adaption, these architectural units may be used for camp sites and picnic spots

In addition, the park houses a large area for tree nurturing plantation with a stewardship program to connect the local community.

The Ecological Riverscape would be an expression of how the cities by Paraíba River will restore balance in their landscape and create community stewardship. The basic framework of the plan integrates three systems – water treatment park, camping/picnic sites, and biodiversity zones. As a consequence of involving local people, the park would showcase the combination of natural and engineered means of restoring with emphasis on establishing a relationship between the citizens living in the valley and the river.

Ecological Riverscape

Interactive waterpark

Camping and picnic spot

Tree plantation program

Cultural Riverscape

The riverscape of Barra Mansa has been reimagined as a new destination in the city for people to recreate, interact and celebrate. From this perspective, the river would be the catalyst of change which will bridge the spatial gap between cities, communities and the river itself through an activated and integrated river edge. The city eventually will become a landmark for cultural events in the valley while at the same time enriching the landscape by fostering ecologically sensitive development.

The Cultural Riverscape is designed to provide a water resilient city edge to bring change in social perception of how people relate to the river. An invigorated access to the water would attract newer prospects of activities along the river edge. The multitude of activities like flea markets, music programs, exhibitions would help keep the space active throughout the day and enable multilayered ecological, economic and social change.

To kick start the project, an accessible waterfront has been created, integrated with the existing recreational facility called SESC. The water is inlet into the park through wetlands, creating a softer edge accessed by three levels of engaging platforms. Through this intervention, people may engage with the water more easily.

At the larger city scale, the strategy is to first create a 100 year flood resilient zone. This will be implemented by softening the riparian edge with the proposed units and by creating permeable surfaces in critical zones. The existing infrastructure has been incorporated to bring the activities and events back to the rivers edge. To test this, the existing abandoned sports facility has been reconfigured to resist flood by raising the floor level by one meter. The space, hence created would become an active public space catering to multiple events for the city. Second phase is to restructure the street scape to manage the storm water, and the third phase is to incorporate the topography of the city which folds into the overall strategy of resiliency we have developed.

The (bottom right) rendering depicts the reconstructed streetscape, designed with permeable surfaces and bio-swale for better storm water management.

To provide a better access to the inaccessible encroached areas along the river banks, floating docks are provided as a means of getting around and bringing people to the water as shown beneath

Cultural riverscape

Softened and strengthened edge

Access through floating dock

Flood resilient street infrastructure

8

Power Plant

Students: Xi Chen, Francisco Jung, Yuri Kim, Fei Xiong

What if the Paraíba River Valley became the forefront of a new energy landscape, and a hub of eco-industry?

Power Plant aims to preempt and remediate the aforementioned post industrial pollution through a symbiotic relationship with agriculture, urbanism and bio-engineering. By integrating energy renewing eco-industries and energy producing invasive “power” plants with the urban fabric, this proposal promotes industrial-urban growth without the environmental side effects.

Throughout the course of history, there has been a rise and fall of industries.1 2 A notable consequence of this industrial rise and decline is the significant environmental repercussions.3 Countries all around the world are turning to sources of renewable energy due to the disastrous global impacts of carbon emissions4 . Brazil is one of the countries following suit and has become the second largest producer of bio-fuel.5 6 7 Befittingly, Brazil has set a high ambition to achieve 85 percent of renewable energy production by 2025.8 9 10 However, in order to accomplish this goal Brazil needs to capitalize on its plethora of land, natural resources and favorable climate by replacing depleting industries with regenerative eco-industries.

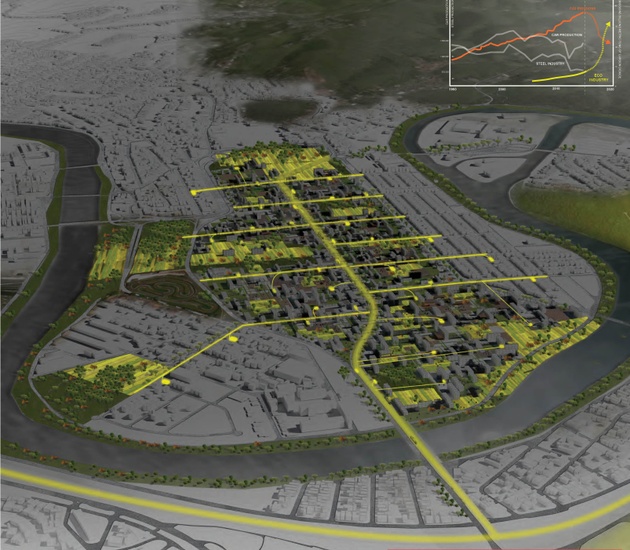

Brazil has heavy industries at various phases from prominent to economically declining.11 The Paraíba River Valley for instance, has prominent automobile industries and a declining steel factory Companhia Siderurgica Nacional (CSN), located in Volta Redonda, that is in dire need of intervention.12 Throughout time, the urban fabric of Volta Redonda has developed around CSN, making the living conditions of the habitants more and more undesirable. CSN is walled off from the rest of the city and its pollution directly affects the river, air, soil and the living conditions of the habitants. Furthermore, the once prominent CSN that promoted the growth of Volta Redonda is now declining due to the lower cost imported steel from China. In addition, CSN is now rapidly converting to automated production methods, which resulted in the reduction of its current work force, leaving the mono-industrial dependent Volta Redonda with a grim unemployment rate.13 In order to alleviate these post industrial conditions, the project addresses the issues at the heart of the problem, and proposes a new energy landscape.

In Volta Redonda, CSN, a once state-owned steel producing company, now owns a vast amount of land after privatization.14 Among these parcels is the former airport located in the center of the city. The current plan is to build a megalithic shopping center at this site. The typology of the proposed shopping center will further segregate the existing neighborhoods from each other, but more importantly it will plateau the economic growth of the city and further jeopardize the already polluted valley. Instead, the defunct airport can be used to introduce a very different type of development—a development that promotes a new type of industry, an eco-friendly industry. This new development will no longer centralize the industry and energy production system but integrates itself within the urban context through an energy producing landscape. With this approach the proposed development will not only promote economic growth in the city of Volta Redonda, but it also promises a healthier environment over time since the landscape remediates and the eco-industry no longer pollutes the environment.

View of eco-industrial neighborhood on currently vacant land

World & Brazil

Brazil is one of the top five polluting countries that consume fossil fuel for energy.15 16 Within the Paraíba River Valley region, there is significant heavy concentration of CO2 emissions due to the heavy industries. However, Brazil is in the forefront of converting to renewable energy as it is the second largest producer of biofuel.17 18 It has the largest algae biofuel plant in the world and is planning to build another on in the Paraíba River Valley.

World carbon emission trajectory

Brazil carbon emission trajectory

World renewable energy trajectory

Brazil renewable energy trajectory

The Paraíba River Valley

The Paraíba River Valley, although plagued by the post industrial decay, has many opportunistic aspects. The warm climate, vast amounts of unproductive land, and easy access to the river are all favorable conditions for the eco-industries to grow the necessary bio-mass.19 The existing transportation infrastructure that connects São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro can accelerate urban development and help the eco-industries to burgeon.20

CSN

Decentralization

Eco-industries consist of research and development, productive landscapes and a powerplant to convert the biomass into energy. Innovations in bio-technology have allowed for biomass powerplants to decrease its physical presence significantly.21 22 Powerplants can now be smaller in scale and housed in a shipping container which allows it to be decentralized and integrated with the urban fabric. In addition, Eco-companies work more efficiently in a decentralized environment since they have a close relationship with the urban context. Its processes depend on food waste, industrial waste, and pollution as sources of nutrients. The powerplant can then generate clean water, energy, and air for the city.23 24 25 26 By interweaving the eco-industry, powerplant, and residential units together, there is a more efficient setup of waste to energy cycle as well as an added experiential value. Residents would live in front of a farm that feeds a powerplant that acts as part of a playground.

Growth and Extension

As this new type of eco-industrial system grows it can not only sustain itself in terms of employment and energy but it can also extend its impact out to the surrounding neighborhood. The aforementioned powerplant can be retrofitted as a public amenity into the existing neighborhood and extend the waste to energy grid from the site to the neighboring residents. Public amenities can also extend into the site to blur the boundaries between the existing neighborhood and the proposed eco-industrial campus.

Phase 1

Based on a flexible implementation framework, the initiative is taken by the eco-industry and the city. Entrade, for example, is a bio-mass powerplant producer that has a business model of going onto the site and planting crops as well as institutions to raise awareness of the waste/plant to energy cycle.27 To spark interest in the community as well as the investors, we propose to activate the existing airstrip in the site by a series of light temporary structures that provide shade, information and fresh crops to the community. This will kick start the eco-company and encourage other companies to join suit.

Phase 1, Air strip reclamation

Phase 2

As interest accumulates, more eco-companies can find their way to the site with supplemental housing that would be completely integrated to the waste and plant to energy system. More productive landscape will be planted to provide for the growth since at least a third of the site must be used to generate adequate energy for the site and its outskirts.

Phase 3

The foundation for the waste and plant to energy system is set in place and its growth will catch momentum by extending the existing transportation infrastructure into the site. In addition, light rail will provide transportation for pedestrians and necessary resources such as the powerplants, waste, and crops at a regional scale into the site. This newly introduced connection between São Paolo and Rio will eventually attract more residents and densification as this new way of living will become a symbol of the future within Brazil.

Sheffield, Hazel. “Tata Steel: 4 Charts That Show Why the UK Steel Industry Is in CrisisTata Steel: 4 Charts That Show Why the UK Steel Industry Is in Crisis.” The Independent. Independent Digital News and Media, 30 Mar. 2016. Web. 15 February 2016.

UK Automotive Industry Targets All-time Manufacturing Records.” SMMT. N.p., 12 June 2012. Web. 15 February 2016.

“BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2012.” Bp.com. N.p., 24 June 2012. Web. 20 February 2016.

Izquierdo, Nieves Lopez. “GRID-Arendal.” Brazilian Biofuels: Infrastructure and Crops. N.p., 27 Feb. 2012. Web. 09 March 2016.

AL-ghaili, Hashem. “Global Sustainable Energy: Current Trends and Future Prospects.”

“Brazil Economic Activity Map.” Brazil Economic Activity Map. N.p., n.d. Web. 12 February 2016.

“World Energy Outlook.” International Energy Agency. N.p., 16 Nov. 2016. Web. 12 March 2016.

Kieffer, Ghislaine, and Toby D. Couture. “Renewable Energy Resources.” (1986): n. pag. IRENA. International Renewable Energy Agency, 2015. Web.

Marin, Pedro L. “Renewable Energies in Spain and in the World.” Development and Possibilities for International Cooperation. Spain. Lecture.

“Shale Energy Revolution.” The Energy Economy (n.d.): n. pag. A Sustainable World Energy Outlook. Energy [r]evolution. Web.

Fraser Martens “Driving Around the World: Auto Manufacturing in Brazil, Canada, France, the UK, and the USA.” EMSI, 02 January 2014. Web 02 March 2016.

Todd Benson, “Brazil’s Steel Giant and Its Company Town Are on the Outs” New York Times, MAY 17 2005, Web 06 March 2016.

Steelorbis, “CSN suspends massive dismissals: Usiminas to start layoff by end of January” 14 January 2016, Web 16 March 2016.

Vanguarda Operária, “Brazilian Steel Company Assault on Six-Hour Day” April 2000, Web 12 March 2016.

Eberhard, Kristin. “All the World’s Carbon Pricing Systems in One Animated Map.” Sightline Institute All the Worlds Carbon Pricing Systems in One Animated Map Comments. N.p., 17 Nov. 2014. Web. 16 March 2016.

Hotz, Robert Lee. “Which Countries Create the Most Ocean Trash?”WSJ. N.p., 12 Feb. 2015. Web. 16 March 2016.

Eisentraut, Anselm. “Technology Roadmap.” SpringerReference (2011): n. pag. International Energy Agency. Web.

TLoveless, Matthew. “Previewing the 2011 Renewable Energy Data Book.” Energy.gov. N.p., 29 Nov. 2012. Web. 15 April 2016.

“Weather Data for Brazil.” Heating & Cooling Degree Days. N.p., n.d. Web. 09 May 2016.

“IBGE, Infrastructura De Transportes.” :: Instituto Brasileiro De Geografia E Estatística. N.p., 2005. Web. 17 March 2016.

“Biocontainer.” Biomass Energy Plants Companies. N.p., n.d. Web. 10 March 2016.

“The Future of Decentralized Energy.” Entrade. N.p., n.d. Web. 04 April 2016.

AL-ghaili, Hashem. “Global Sustainable Energy: Current Trends and Future Prospects.”

Wastewater Purification Using Algae for Biodiesel.” Climate CoLab. N.p., n.d. Web. 19 March 2016.

“Cultivation of Algae Strains, Species for Biodiesel, Algal Farming for Biodiesel - Oilgae - Oil from Algae.” Cultivation of Algae Strains, Species for Biodiesel, Algal Farming for Biodiesel – Oilgae - Oil from Algae. N.p., n.d. Web. 01 April 2016.

White, Francis. “Study: Algae Could Replace 17% of U.S. Oil Imports.”PNNL: Pacific Northwest National Laboratory. N.p., 13 Apr. 2011. Web. 17 March 2016.

This is the footnote text 22

AFTERWORD

Beyond the Studio

Our shared goals for this innovative design studio collaboration with Columbia, UFRJ, and UGB Volta Redonda was to have its results provide a real, on-the ground contribution to the transformation of local reality. In a studio that brings together so many different nationalities and perspectives, we had an ever-constant concern to keep a strong and significant link with the spatial environ so that our vision did not fall into the common trap of easy stereotypes.

However, there was at the same time a great concern to not submit ourselves to the right-and-wrong recommendations of “business as usual” or default to what is usually done. We aimed to challenge this technocratic view and take advantage of an opportunity for innovation in order to think about the process of urbanization within our region differently. The historical and geographical entity known as ‘Paraiba Valley’ goes far beyond the study area. It was chosen as a study area not only because of its relevance as the main source of water supply for the Metropolitan Region of Rio de Janeiro, but also because of its great potential in terms of development (given its position along the country’s main economic corridor) when compared to the São Paulo portion of the valley. This potential is a consequence of the greater polarization exerted by the city of Rio de Janeiro and the relatively minor economic role assigned to the hinterland of its own state. Indeed, the São Paulo portion of the valley reached a higher level of development and its environmental problems are now more comparatively more complex due to the accelerated pace of urbanization and industrialization patterns. The region of the Mid-Paraiba, where the cities of Resende, Barra Mansa and Volta Redonda are located, has thus more favorable conditions for rethinking the development model and relaunching the regional economy on different bases. We call this ability to literally skip the already known stages of development, a leapfrog. And that’s what we tried to convey in studio in terms of urban design thinking.

In this sense, we believe that having water as a central issue was strongly strategic in that it intrinsically calls for a holistic approach to urbanism. By taking into consideration its multiple implications, the contribution of the studio was to instigate in each of the proposals a critical view on the main elements that compose the current development model. Following the order used here to present the projects, students questioned the under-utilization of the existing railway infrastructure resulting from the adopted concession and privatization standards, the extreme concentration of resources to operate the largest water treatment plant in the world, the municipal land use policies allowing the urbanization of rural properties and their conversion into detached gated communities with no counterpart in terms of infrastructure, nor the improvement of already existing urban areas, the housing program Minha Casa Minha Vida sponsored by the Federal Government that has been a partner of such land predatory logics, the abstract guidelines of the national Forest Code that do not take into account the specificities of land use along the river banks and the insufficient incentive to foster new types of economic activities and modes of urbanization that could be implemented thanks to the generation of alternative energies such as biomass.

Differing from purely critical approaches, the ambition of the studio was to use the project as a means of research to explore these issues and to help overcome the problems they generate. In this sense, the design strategies embrace the concept of multipurpose infrastructure not only for the ability to combine more than one target in the same project, but also as a way to expand the range of stakeholders and possible partners interested in collaborating and helping to implement the proposed interventions.

This approach is already generating concrete results. The recently elected city administrations that have been in office since last January have already shown interest in getting to know the work published here and a seminar to start discussing these visions and projects is scheduled to take place this next June. In addition, International NGOs have already expressed their interest in help funding the implementation of a pilot case of Collective Waterscapes and a workshop should take place in August to begin its construction.

These are some encouraging signs of the effects transnational collaborations can have, and indicate the role that Universities like the ones involved in this effort are now called on to play as driving forces to make the world a better place to live.

Columbia University

Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation

Urban Design Program

Avery Hall, 1172 Amsterdam Avenue

New York, NY 10027

United States of America

Faculty

Kate Orff, Coordinator

Ziad Jamaleddine

Petra Kempf

Laura Kurgan

Guilherme Lassance

Geeta Mehta

Students Dhruv Batra, Hannah Beall, Guangyue Cao, Jiajing Cao, Xi Chen, Serena Ceada Fernandes, Nicolle Rebecca Gitlin, Eleni Gklinou, Francisco Jung, Surbhi Kamboj, Yuri Kim, Xinye Li, Ni- shant Samir Mehta, Shiwani Pol, Graci Salisbury Mills, Yi-Yen Wang, Fei Xiong, Ziyang Zeng, Lee Yan Shun, Ashwini Karanth

Special Thanks

Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Centro Universitário Geraldo Di Biase and Studio-X Rio