Introduction

Beyond the Digital Interface

We are stuck at home.

Over the course of the last few months, our relationship to and our understanding of intimacy, space, and architecture has drastically shifted. This exhibition is the byproduct of the absence of bodies, composed of documents drafted and shared across the internet from our respective residences. Current conditions have given rise to a set of virtual limitations in the forms of codes, templates, and above all, the structure of language.

For the End of Year Show, we decided to investigate this new reality and form a lexicon of our own understanding of what is happening in the world by engaging in the residue of our transactions and exchanges across the internet. Our final project activates the bottleneck of the screen by reducing works into a concatenation of concepts. In turn, we are highlighting that behind the definition of a concept lies a story, message, memory, and perceived truth.

Each entry logs a conversation between us, the first year CCCP students, and the program’s graduating class of 2020, whose thesis work catalyzes, infiltrates, and meditates on the exchange of ideas, concerns, and shared urgencies; drawn together across suburbs and cityscapes; text and image; zoom, facetime, and google documents.

Welcome to the new normal.

1

Accident

May 2, 2020, Zoom

Zoe Kauder Nalebuff is a New-York based artist and writer. Her thesis, “An Accidental Archive,” catalogs material from Frank J. Thomas’ commercial career as an insurance photographer in Los Angeles from 1950-70, considering what is at stake in the large collection of images of stairs, floors, ramps, and landings—records of sites where accidents took place.

Zoe Kauder Nalebuff, An Accidental Archive, Advisor: Mark Wasiuta

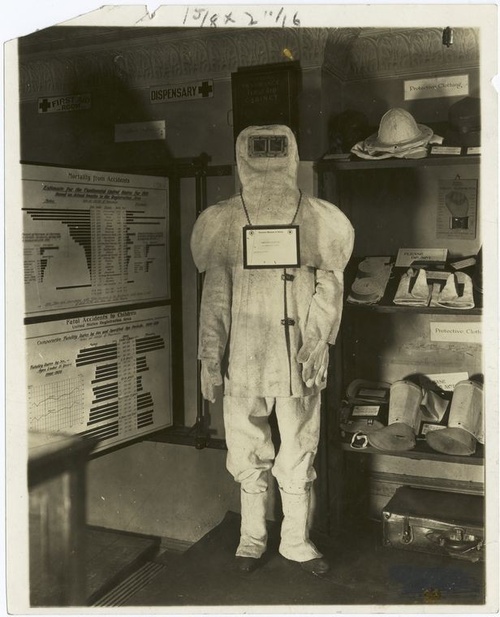

Asbestos clothing for hazardous work, from an exhibit in the American Museum of Safety, New Yo...

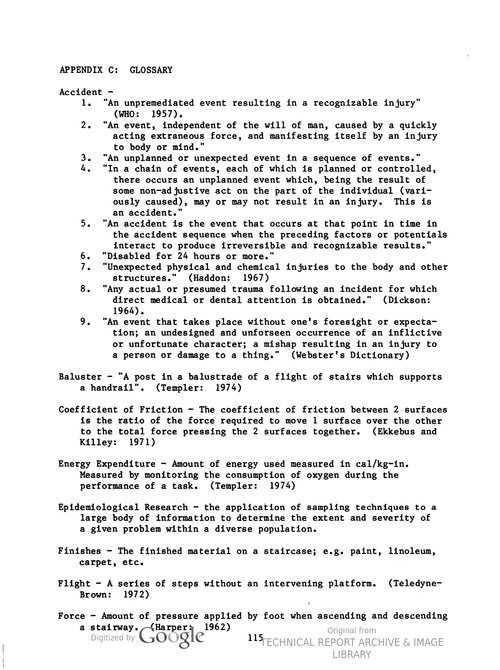

Guidelines for stair safety. Center for Building Technology, Consumer Product Safety Commissio...

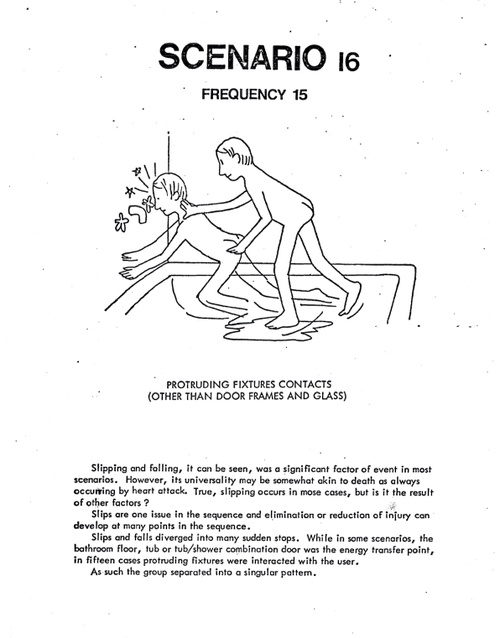

Accident Scenario 16. A Systematic Program to Reduce the Incidence and Severity of Bathtub and...

Flower Appliqué. A Systematic Program to Reduce the Incidence and Severity of Bathtub and Show...

Emmanuel Olunkwa and Zoe Kauder Nalebuff

American Museum of Safety Annual Meeting and Banquet. Rare Book Division, The New Yor...

[Emmanuel Olunkwa]: I like this lack of language, this exposure of and to its shortcomings because of how it composites and nestles itself in a space that’s linguistic, ethereal and beyond us, in an elsewhere that lingers in some sort of ideation, but that it’s also a physical act—something that can actually be embodied. You talk about the slippages of accidents; can you speak to the limitations and framings of it?

[Zoe Kauder Nalebuff]: I feel like what you’re talking about in terms of your work, the place where this work is being done, and of which I believe in so deeply, and one of the places I believe it exists the most, is around blackness, and around the American experience—thinking about Christina Sharpe and Dionne Brand. And the way that poetry is necessary to an architectural living, to shed everything not only what language does but what language conceals. One of the things that I think brings these things together is the lack of support, lack of belief, lack of willingness to accept that structures and language are upholding certain ideals. When I was living in Chicago, I worked with Torkwase Dyson on her show at the Graham Foundation. Working on her show every day I was able to witness her through different attempts of essentially crafting a new language with her work—witnessing that process and seeing the form of self-doubt, uncertainty and the uneven terrain, and then experiencing a shift of simply having to believe in the work. Like the sheer fact that you have to have some type of belief in the work that you’re doing, otherwise, you’ll go crazy.

[EO]: I was wondering what’s at stake for you both within and through this project. I’m in Saidiya Hartman and Mabel Wilson’s class on architectural enclosures and confinements. In what you’re posing, I want to ask you about the confinements of language surrounding the notion of risks.

[ZKN]: It all begins around the secular church of statistics and the beginning in World War II, in terms of forms of management and information control, of a new belief in statistics as a way of adjusting a feeling of control rather than having control. It’s as though if we have the numbers, we have a kind of clarity or truth.

[EO]: Right, the thing that’s most compelling to me is the causation of certain risks and the language around faulting. To think through the leading causations of accidents, to pin down the specific of risks: stairs, ramps, landings, and floors and the fact that yet they are everywhere—they are the standard. Why are stairs the standard when structuring a building? Is that what you’re concerned with in your project?

[ZKN]: There has been attention and acknowledgment of falling and the dangers of these architectural consumer products for much longer than since the implementation of law surrounding accidents in 1974, and this is what my research is about. You have attention to it again and again, but it just stops short of addressing and considering fully the accidents that happen at home. You have the workers’ compensation movement come out of the labor safety movement, which is predicated on the experience of mass accident all-at-once.

[EO]: What’s a mass accident?

[ZKN]: In the United States, the foundation of the labor movement for worker compensation comes after the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire that happened on March 25th in 1911. And you have an outrage over the loss of productive labor, you have this collective outrage, and workers’ compensation takes a long time to come into effect, but there is suddenly national attention and concern over accidents in the workplace and so you have accidents become a subject of study—like slippery floors—from the National Bureau of Studies from the 1910s onwards. There are small moments where it’s addressed in different ways, but accidents at home are not given the same treatment in part because there is no concerted outrage, in part because these accidents happen alone, because the movement for what to do about domestic labor and women in the workforce, the move for progress was to go into equal access for the workforce rather than seeking compensation for domestic labor. You know, it’s not that domestic labor doesn’t happen, but that it is uncompensated. To take Françoise Vergès “shit work” idea—it’s not just that domestic work is mainly done by black and brown people, but also there is no recourse for when the domestic space is a site of work. This is what I’m trying to track in my research and what I argue over and over again: these moments of addressing accidents when they do turn their attention to home—accidents are suddenly inevitable and due to neglect—but in the workplace we have decided to classify them differently.

[EO]: What you’re saying reminds me of the notions and implications of insurance–specifically, how it fails the imagination because of the limitations of what requires coverage. It makes me think of the failures of language and failing into a new zone of temporality and causality, in that it’s not so much that accidents don’t happen—it’s that accidents shouldn’t happen. The issue lies in the structuring of accidents being presented as being preventable, but it’s undeniable that accidents will happen. We don’t know and one can’t predict them. But what do you? What do we want to do with that knowledge? It quite literally is an architectural issue because it’s like something that one can aspire to control, but the perpetually failing structure that dresses itself up like many different things: danger, policy, infrastructure, mobility, and language—all of which inhibit that kind of understanding.

[ZKN]: I find myself in this sort of stumbling pattern or cycle, where I’m drawn to these ideas and I can’t really make sense of why I’m drawn to them. I struggle to articulate why I am drawn to them, I struggle with the language of articulating the kernel, the thorniness of the knot at whatever I’m trying to pull at. This project crystalizes that this is what I’m getting into, a place where I’m struggling with language because ultimately what I’m most interested in is that there is no language for what gets classified as a risk.

The battle of this year was to allow myself space to accept that there isn’t a body of research or scholarship or actual subject or discipline that what I’m interested in sits inside of; I wasn’t finding anything. I was researching and nothing existed on accidents and I was thinking about taking the experience and actually understanding and accepting it as a piece of the puzzle, as a document, or evidence, or as a reflection of my failure to locate material. I just find it to be an interesting challenge to get over thinking that I am the problem or that my capacity for language is the problem to actually taking those realities as symptoms of something not as reflective of me. In this project, that subject and the missing language and missing attention happens to be accidents and around minor accidents. I feel like my work is filled with so much self-doubt about language and communication because I’m circling around a lacuna.

2

Development

May 6, 2020, Zoom

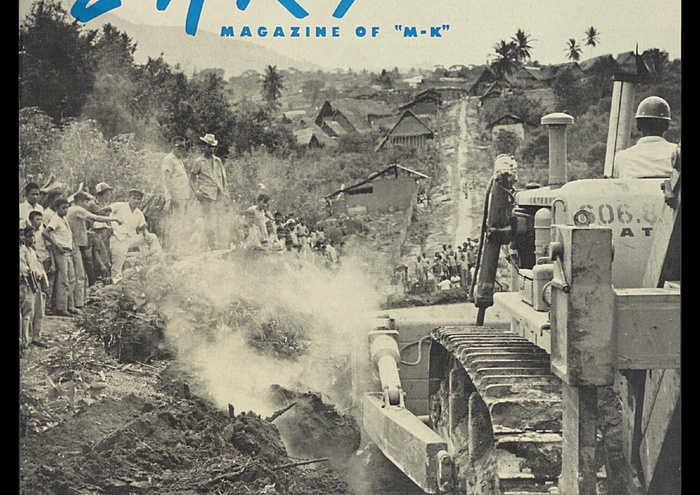

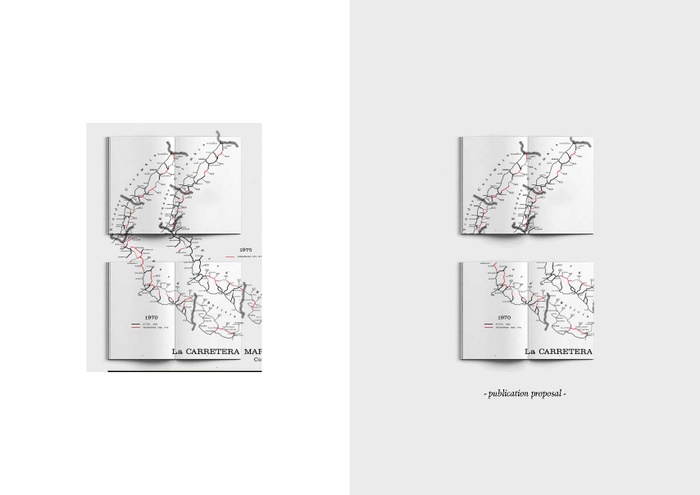

Jose Luis Villanueva is an architect and researcher whose thesis examines the Marginal de la Selva, a colossal highway imagined by Peruvian president and architect Fernando Belaunde in the 1960s. The project was envisioned to promote the geographic, political, economic, and social integration of South America’s tropical territories, while establishing a continental-scale infrastructural connectivity network. By using the Marginal de la Selva as the core of analysis, the thesis suggests how infrastructure, development, nationalism, and governance became rooted in landscapes and bodies, consolidating new social and political subjectivities while producing extreme changes in the Amazon’s ecology.

Jose Luis Villanueva, A Line in the Rainforest, Advisor: Mark Wasiuta

[Caitlyn Campbell]: This program is based under the framework of three key themes to what I’ll refer to as non-professional, historical/abstract architecture: “critical, curatorial, conceptual practices.” Do you feel that there is one of these particular themes your work falls under? Why? How do you think that has changed over the course of the project?

[Jose Luis Villanueva]: This project responds directly to the “critical” aspects of the program. With the flexibility the thesis provides, I initially wanted to utilize my background as a professional architect and my graphic design knowledge, but you really need to understand where the material takes you and follow that. The project has expanded into a history/theory-based paper. Change occurred a lot over the course of the process as I continued to find such rich archival information, maps, records, and photography. I figured out it would be better to use them as tools as they are, rather than to create a visual homage to them. Then it was a matter of how I manage to analyze this material.

[CC]: What was the initial impetus of the project and how would you describe the greatest changes to your process and the outcome?

[JLV]: Before I came to CCCP I worked for two years in the Amazon as a professional architect designing schools for children and working with the government and Ministry of Education. It was through this experience that I was able to research it a little bit in terms of design for outreach. I needed a change. So, I wanted to do something related to the Amazon, the government, and architecture. The Amazon is such a complex territory. It is a site compounded with unique landscapes and defined by relationships between indigenous communities. The project shifted when I was going through the archival material about the government and found out about the huge highway through the middle of the Amazon. His story was so fascinating it became more of a historical research paper on Belaunde as I got more invested learning about this highway in the 1960s. He was very well known. I was familiar with his work within academic discourse as a student and I had studied [his] projects in big cities, single-family homes, and high-rise buildings, but not of his work mediated through the Amazon, agriculture, and rural Peru.

[CC]: The two words originally assigned to you were “Propaganda & Development.” Reading your Review II text in more detail, how would you say the word “development” operates in perhaps more ways than one in your research?

[JLV]: Putting those terms first, specifically within the context, of the beginning of the project related to the work of James Scott when he describes this 20th-century ideology of the “high modernist.” These notions of how to master nature, including human nature, at different scales, is central. Entanglement of both future and past [comes into play] when we think in terms of the contexts of the site of the Amazon. There lies a deep history presence of progress and development across the Peruvian landscape dating back to the Incas. Belaunde argued that Peruvians should tap into this ancestral knowledge. The transformation into today’s global contexts echoes this tradition of development

When you think about this in terms of the Cold War and the word “development,” you have to see it as an entanglement of labor with land transformation and technology to support these tools and progress. How Belaunde transformed development in the Amazon as something not foreign is really interesting to consider. Of course, this was achieved through propaganda. Belaunde’s beliefs regarding development balance a longing for the future while rooted in the use of traditional infrastructural practices based on specific ideas of locality.

This includes the communities themselves becoming a form of machinery. During those days, development was equated with airports, big seaports, and large-scale systems of infrastructure. In the United States, dams and railroads were the benchmark standard of development. Conversely, the rudimentary change to the environment within Belaunde’s project addresses development still on a large scale, but as something not very technologically-advanced and rooted in indigenous involvement.

[CC]: Could you speak to the ways in which the “Development” interacts with scale?

[JLV]: In terms of scale, when you think about infrastructure and development during the 60s, you usually think about big infrastructure and heavy machinery. But Belaunde managed to create this rhetoric by which “development” could be achieved with just a small rudimentary tool—a shovel—changing notions of scale too.

If we think specifically to the term “scale” in relation in the development as a spatial operation, consider the sets of aerial photography of the Amazon used by the project. This was the first time the Peruvian government could easily see that the river system was the main “river as the road to the Amazon” and growth and development had to begin here.

Furthermore, the word “visibility” could also be utilized to describe the work. Visibility in terms of making something legible from the texts to analyzing feasibility studies, maps, diagrams, images, and photography. The ways in which one erases the layers on complexity to make something as impenetrable as the Amazon visible was quite something. Visible of how we start translating territory and subjects into something you can manipulate and change.

[CC]: I have to ask: What are the ways in which your research has been affected by the pandemic?

[JLV]: Of course, all of the research has been affected in practical ways with archival material, textual documents, and books from Avery Library unavailable. I had a strategic plan carefully organized around reading specific literature throughout the process in a specific order which obviously changed. [I found myself] thinking back to the foundations of the program and its investigation of the the “document” and how this operates. I put this in front of me and started writing from there. The quarantine period has forced me to pause as a researcher and reflect on how our arguments come together like a puzzle when you engage with a specific reference or visual material rather than using them as a guide to structuring your work. The final publication format came out of this explication.

[CC]: Working within the contexts of the pandemic and your work more specifically, how can you use your project to think through the distinction between the natural and manmade environment?

[JLV]: Related to the Amazon in particular and looking at the relationship between governments, architecture, and the environment, it brings me to this interesting question of how, as an architect, I can approach this as a site of entanglement and complex networks. We can look at how Belaunde began to make very specific changes to the ecology as well as the local culture in the Amazon of Peru. Everything gets so broadly visible as one moves across the historical landscape. Every process you do through design, indigenous communities, nature must speak to this in some way. And even still, the very definition/separation of the natural and manmade environments is something that it has to be put into question in the Amazon.

[CC]: Thinking about the life of the research beyond this project, what are some questions that you would still like to ask regarding this topic or the themes explored in the work? Or, do you feel that the research addressed all aspects? In short, do you feel the narrative is finished? How do you plan on following up on this research in the future?

[JLV]: I see this as the first phase in a series of projects related to the Amazon moving beyond the borders of Peru. This first iteration has driven me to pursue this area of investigation beyond the traditional dimensions of architectural practice(s), [looking at] Brazil and other South American countries with Belaunde’s work as an entry point to explore the interaction of infrastructure and natural landscapes in complex territories.

Crucial to my personal exploration, also, is the critical role of architects in Cooperacion Popular’s program, an initiative promoted by Peru’s government in the 60s where indigenous communities were encouraged to participate in development projects with free labor.

Finally, there are several projects in the works that will see the dredging of the Amazon waterways over the next two to three-year period. We will see a substantial increase in the number of large vessels encroaching on the landscape. This will transform the river systems across the region. Can you imagine how that will change everything?

3

Food

May 2, 2020, Zoom

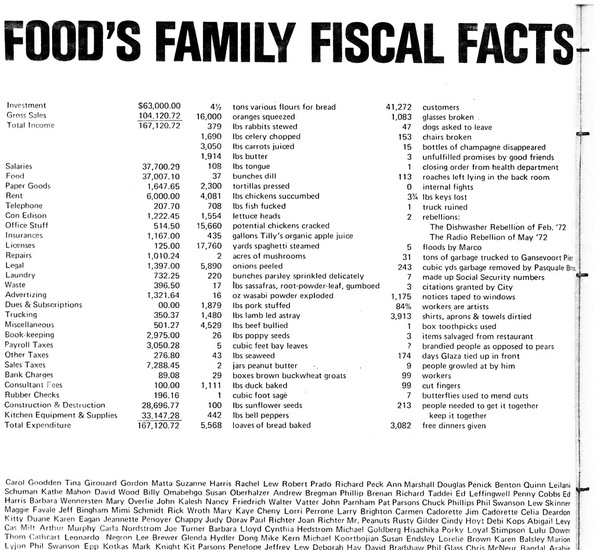

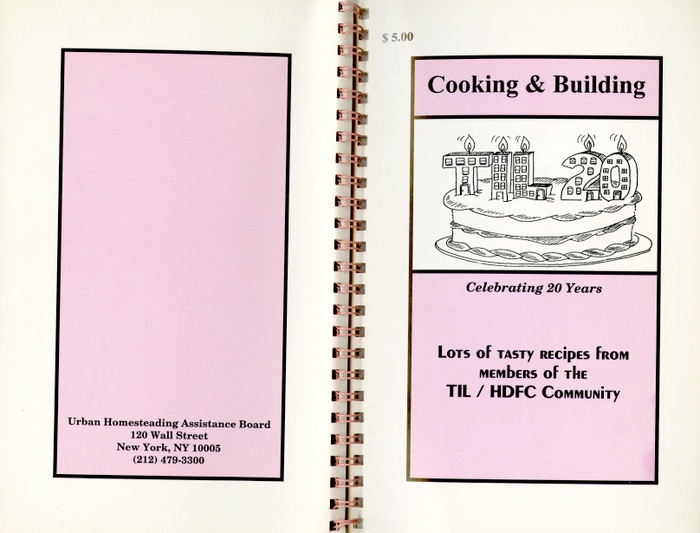

Emma Leigh Macdonald is a Masters of Science graduate in Critical, Curatorial, and Conceptual Practices in Architecture at Columbia GSAPP. Her thesis “Place Setting” situates itself around the claim that through its participation in vast scales of production and consumption, food is able to create both global systems and environments that are deeply personal. Building on the contexts of precarity and experimentation within the built environment of 1970’s New York, Macdonald highlights practices including the Urban Homesteading Assistance Board, guerrilla community gardening on the Lower East Side, and art spaces such as FOOD restaurant and The Kitchen. Through the use of instructional formats such as the score and the recipe within its text, “Place Setting” attempts a format that invites participation in its consumption—even at a distance.

Emma Leigh Macdonald, Place Setting, Advisor: Felicity Scott

[Ben Goldner]: Your research is situated around movements within the built environment of 1970s downtown New York. What was it about this point in time that potentiated these kinds of projects and subsequently drew your attention to them?

[Emma Macdonald]: I think that moment in New York feels like a kind of origin point to a lot of issues we are thinking about today, it being the kind of beginning of the neoliberal state as well as a time when public discussion of a lot of environmental concerns was happening. In New York in particular, there was such a housing and economic crisis partly because of people moving en masse to suburban areas, which resulted in a lot of empty units but also a real lack of public services. What I think that made room for, in some cases, were the ways people stepped in—outside of, say, formally-provided infrastructure services or market-based housing—to provide those things for themselves and their communities. Also, a lot of community gardens that still exist on the Lower East Side starting popping up during that time because of empty lots that no one had the money or city support to build up. That sort of resourcefulness and experimentation definitely spurred my interest towards Tina Girouard’s Swept House.

Tina Girouard, “Swept House,” 1971.

[BG]: I’m glad you brought up “Swept House.” In your essay, you pose the question, “What does it mean to question the bounds of the domestic at a moment in which we are confined to that space?” Do you think, perhaps, that the confinement we are currently experiencing might offer the same perspective Tina Girouard’s Swept House created, insofar as instead of seeing no walls, all we see now are walls?

[EM]: To me, “Swept House” is a performance in creating a domestic space out of nothing and kind of a blurring of public and private space. It brings an action which is usually only in the home, and usually associated with women and with private space, into such a public setting under the Brooklyn Bridge. The idea that art practices should be collaborative and that public and private should be blurred came up in a lot of Girouard’s work. To me, that seems super connected to the fact that she was living and working at a time when there was so little access to domestic space. In surreal timing, she actually just passed away at the end of April, at 73, which feels like an important reminder to consider her work in her memory as so many of the domestic issues she focused on are now front-of-mind for us all.

[BG]: You’re right, her work seems so prescient and meaningful right now. I wonder how it might be contextualized in the current environment. Whereas in the 1970s there was a housing crisis and a lack of domestic space, it almost seems like now there is nothing but domestic space.

[EM]: Exactly. I think that what I was latching onto about “Swept House” was the notion of creating a domestic space out of nothing. Except now we are creating everything out of our domestic space. Her work is a nice prompt for thinking how to bring others into private space or to create collaborative, shared spaces of being. That question definitely has a whole new set of bounds right now. I think that her work is a nice charge to think about ways of creating shared and communal spaces because that sort of language is used plenty now in ways that don’t refer to the kind of ideals that these different communities in the ’70s were thinking about—things like “shared co-working spaces” or the “shared economy.”

[BG]: It’s almost as if these sorts of political/economic forces that are focused on the loss of these shared co-working spaces and this shared economy we are hyper-aware of are sort of co-opting the vocabulary she championed in the 1970s. What looking at her work now might do is make us that much more aware of those other public and communal spaces that we’ve also lost access to.

Changing gears just slightly: the public, communal spaces you reference in your work as sites for “livable interdependency” all had as their central focus the concept of, as you say, the meal as “an architect of shared space.” What is it, do you think, about the activity of eating a meal together that activates a space so uniquely?

[EM]: I think I’m just really interested in actions that are at once extremely practical but also performative. Food is such an immediate necessity as well as something that can communicate so much or be an art practice or a meaningful event. Its ability to cross so many scales and concerns are what allows it to be something we can gather around and connect to others who we otherwise might have little to connect over.

[BG]: That definitely speaks to the sort of ineffable, interdisciplinary state of being that food has. It’s also such a direct reference to the FOOD restaurant Girouard started with Carol Gooden and Gordon Matta-Clark. As you mention in your paper, FOOD was first and foremost a place to provide jobs for artists and to provide food for artists. At its core it was still a restaurant: it was feeding people, it had a budget, it was a process of labor. Food is such an immediate, consumable manifestation of someone’s labor. It’s very evident that some work went into this thing you are consuming.

FOOD spreadsheet.

[EM]: I think that’s a really nice way to put it and a nice point to think about. Being aware of that process feels like a nice addition to the idea of community being based on interdependency and reciprocity.

[BG]: Speaking of those kinds of interaction, you had originally planned for your work to be presented in a public gallery setting, with a recreation of Girouard’s “Swept House” for visitors to walk through. How do you think the inability to now do this and your subsequent switch to a publication format has altered or re-contextualized your piece?

[EM]: I think that some sort of participation always seemed so important in presenting this work. The inclusion of scores and recipes as a kind of guide to taking in texts is something that feels really interesting as a model for engaging in a book. Sharing or offering experiences at a distance offers its own conceptual windows to how everyone might read or experience things differently. I’m really interested in the idea of including instructions or little experiences built into a text that might influence how someone reads it.

[BG]: Do you think the “score” and the “recipe,” as conceptual extensions of the meal, have been given new meaning in an age where their ability to be shared has in fact not become necessarily inhibited?

[EM]: The score and the recipe seem like such amazing formats for communication at a distance during this time. The intention to be a very clear set of instructions, but also to leave room for interpretation and different contexts, is really important. I wonder if that is related to why cooking and sharing recipes and photos of what everyone has made is so popular right now and has exploded so much.

Urban Homesteading Assistance Board supported home, 1979.

Urban Homesteading Assistance Board Cookbook.

[BG]: So, with all that being said, what recipes have you been looking at recently?

[EM]: There’s a recipe for each chapter of the work actually. They are all related to the subject matter of the chapter, but the first recipe is actually for a starter.

[BG]: I’ve got some bread in the oven right now actually.

[EM]: The rye flour has really helped.

[BG]: We made a rye starter but the other flour we initially used was this hard, red wheat flour and it was just not working for some reason. The loaves were coming out a bit stodgy. But there’s different flour in the oven now, so we’ll see what happens.

[EM]: I saw that you made pavlova recently. Did you use the St. John recipe?

[BG]: You know it’s funny because I have a pavlova recipe I’ve used in the past and kind of just automatically used that one again. I didn’t remember until afterwards that there was a pavlova recipe in the St. John cookbook.

[EM]: I wonder how different the recipes are.

[BG]: Not huge. I like to drizzle some balsamic vinegar on the fruit. Also, the St. John recipe calls for ten egg whites. That’s an enormous pavlova.

[EM]: We should make the big one when it’s possible for a lot of people to eat it.

4

Infrastructure

May 4, 2020, Zoom

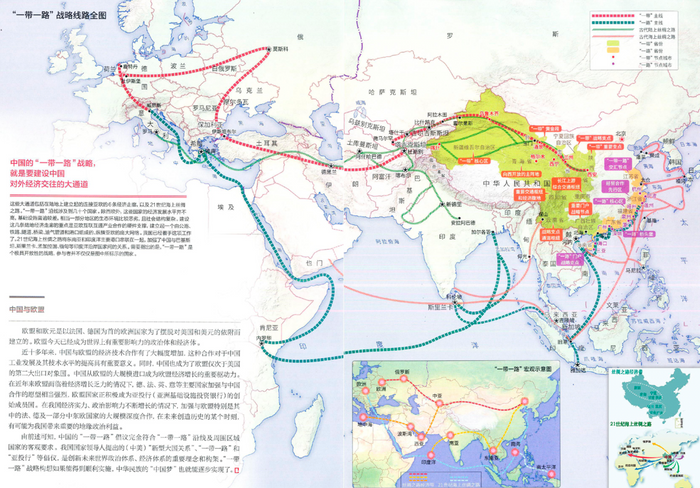

Isabelle Tan is a writer and researcher based in New York. Her thesis, “How to See the BRI,” provides a critical handbook that entangles the political, economic, infrastructural, and mediatic complications of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). By reassessing the technical systems that bind us to the world, “How to See the BRI” offers a transcalar view: one in which the sight of the BRI zooms in and out from documents to the pipelines, and from campaign videos to oral stories.

Isabelle Tan, How to See the BRI, Advisor: Mark Wasiuta

“Yidai Yilu’ Zhanle Xianly Quan Tu” [Belt and Road Strategic Map], Zhengzong Lao Ran (blog), August 1, 2017.

[Ruihong Li]: As I was reading through your “How to See the BRI” handbook earlier today, I was really struck by how it unpacks the mediatic aspect of infrastructures in such a smart way. It seems that a big part of your thesis now focuses on questions of mediation. But having followed your project on the occasion of multiple reviews, I noticed that your thesis has shifted, strengthened, and transformed in terms of scope, argument, mode of address, etc. What was your initial idea and how has the project moved into its current form over the course of the year?

[Isabelle Tan]: To be honest, I didn’t start out with any kind of concept of mediation, or at least it wasn’t a conscious framework. In my initial research, the BRI appeared gray, like a gray architecture of sorts, but I had trouble explaining exactly what I meant by this. I didn’t realize it then, but I was really trying to get at the dialectical ways in which infrastructures operate, oftentimes ambiguously, but how this is part of its work. The notion of something being gray—neither black nor white, but rather in-between—really captured this aspect of the BRI for me, and so it stuck.

Screenshots of music video “I’d Like to Build the World a Road,“ video, People’s Daily, September 10, 2018. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LLm2m9Sw8ZA.

[RL]: Yes, the concept of gray is a really productive tool for understanding infrastructure. The quality of being gray, as explored in literature, is the quality of being outside, uninteresting, and unpopular. For example, administrative documents, user manuals, court reports, and so on are all considered gray literature, a kind of writing marginal to the main literary event. If gray architecture has a similar quality, what does it mean to study it in an architecture school?

[IT]: Before my construction-site visit to a tunnel for the BRI high-speed rail in Indonesia, the research I had done was entirely carried-out from the space of my laptop. The various materials I gathered were all online, and most of these materials might be considered gray literature. They were feasibility reports, technical documents, and government texts pulled from Chinese state outlets and Indonesian news basically referred to Chinese ones. I only managed to find a few primary sources about the development of the rail, so the ethnographic engagements of conducting interviews and the conversations that arose from my site visit were extremely formative. The question about what it means to study such literature in architecture is an important one—something that Mark Wigley aptly pointed out in one of my reviews. I think my answer is that by not focusing so much on the standalone building or the genius architect, I hope my project will bring to fore discussions about the relations that form architecture as a discourse itself. It might help us understand, let’s say, the representation or mediatic functions of architecture, and more broadly the built environment that encodes, records, and transmits relations, and thus something that sustains, conditions, and articulates life.

Jane Perlez, “With Allies Feeling Choked, Xi Loosens His Grip on China’s Global Building Push,” New York Times, April 26, 2019 (print edition).

[RL]: Totally. Infrastructure is a great site to engage this kind of discourse of more complex and relational nature, as infrastructure cuts across so many different spheres and has a profound condition of being “in media res.” Many interesting thinkers who deal with infrastructure in recent decades have a media-theory twist. Take for instance Brian Larkin, who has written extensively on this subject: he highlights the visibility and invisibility of infrastructure as a kind of political aesthetic, in that, for him, the ways in which we experience, sense, and interact with infrastructure are politically charged. I know that you took his class this semester in Columbia’s Anthropology department. How has his attention to the infrastructural (in)visibility been formative to your work?

[IT]: Brian is such a knowledgeable scholar on this subject. The threshold between visibility and invisibility of the BRI has always been a kind of tricky area to navigate and think through, because—as I suggest in my paper—a large amount of the information that I got from the preliminary document-based research would later prove to be in blatant contradictions of what I got in the field. For instance, in New York, I read that the tunnel-boring machine used for the drilling of the tunnel for the high-speed rail was running 24-hours a day without pause, drilling at a rate of 8 to 10 meters a day. This was actually very believable. As I delved deeper into those texts—following a paper trail of seeing and knowing—I could imagine a large optimizing technical potion fueling humanity’s march to the end, as fires burned and machines ran incessantly. But the kind of temporality that those documents exist in contrasted significantly with the timeline at the construction site. The day I visited the Tunnel #1 site it was raining, and the tunnel-boring machine wasn’t running. The project manager I spoke to almost smiled when he said the machine only runs for a couple of hours a day even when it is not raining. We know of no system that functions perfectly, without losses, wear and tear error, accidents, or opacity. I think this was a key moment. It led to the kind of slippery mediation issues that my thesis is invested in. One task for me now is to more precisely describe visibility/invisibility and the kind of mechanisms that enact this in relation to the BRI or to more precisely point to critical moments of where to look. I think I have a better sense of this now and would like to continue this work, but the BRI has this weird way of slipping away from you.

ESPO Pipeline that runs 4,857 km (3,018 mi) from Taishet, Russia to Daqing, China.

5

Materiality

May 7, Zoom

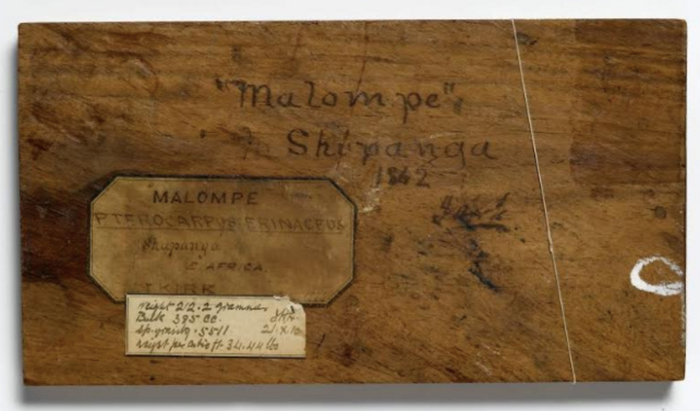

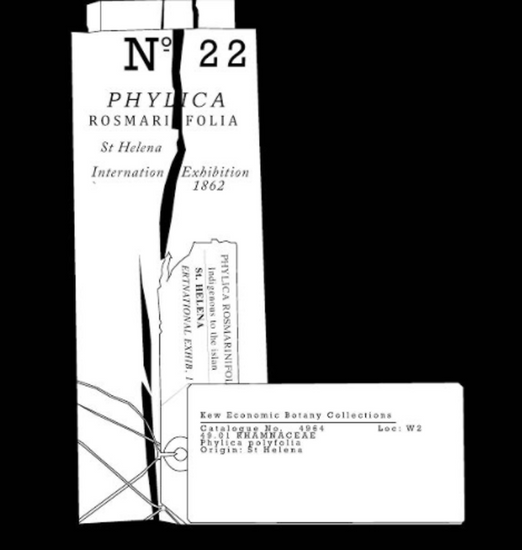

Francesca Johansonis a writer and researcher. Focusing on botanical collections of wood, her thesis, “Xylaria: Archives and Economies of Wood” attempts to read the scientific specimen as a document that records, circulates, and produces knowledge for different actors at different levels of government.

Francesca Johanson, *Xylaria: Archives and Economies of Wood, Advisor: Felicity Scott

[Caitlyn Campbell]: What was the initial impetus of the project and how would you describe the greatest changes to your process and the final outcome?

[Francesca Johanson]: I have always been interested in the botanical archive. By using an expansive definition of a (scientific) document, and by framing an archive as a process, I have been able to explore these spaces in more depth. I am particularly drawn to botanical archives that have not yet been written about. Work has been done on herbaria, but xylaria, not so much. Through my research I began to unveil connections to industry, forestry, and agriculture, as well as changing epistemologies in science and the relationship between these entities. I am interested in exploring what diving into a specific botanical archive tells us about the production of knowledge.

[CC]: In your thesis you state: “These three episodes are by no means representative; the aim of this thesis is not to totalize the history of the wood archive, least of all, the material culture or history of wood, but to explore in detail the work of the archive.” In relation to this, how do you reflect upon “materiality” in terms of the final production of your work?

[FJ]: The project raises comprehensive questions of material culture that emerged out of the literature dating between 1850 and WWI with specific questions related to industry in Britain. If we consider wood in the archive, in terms of commerce and science, we can ask, what alternative landscapes and economies have been recorded that are not yet on display.

[CC]: In your writing, you describe how your research is organized by four scales. You put it so eloquently: “[the research] zooms back and forth from the cellular to the macroeconomic, positioning the wood specimen in a wider discourse on imperial governance. It examines the wood specimen under the microscope (interrogating regimes of cellular control), in the archive, where its formal and scriptural qualities are parsed, and in host-institutions. Relations between a specimen—as an object that inscribes, produces, and circulates knowledge—and territorial regimes thread this thesis together.” Could you specifically address the multidimensional notions of “scale” within your work? How do you think this has transformed and evolved over the course of the research?

[FJ]: In my research wood collections are dealt with at different scales. The specimen, the shelf, the institution, the nation-state. I think “Empire” is the largest scale I work with within this project. Understanding the microaggressions and the politics of the more banal moments of colonization, especially when botany is concerned, made me reflect on the idea that certain acts of violence are hard to see. Thinking about wood as an institutional specimen—as something you can hold in your hand—has been consistent throughout the project.

[CC]: I cannot help but find myself asking questions related to the distinction of flora and fauna in the context of the current pandemic. How have you thought about your research in relation to this global crisis?

[FJ]: From a format perspective, I had originally hoped, but was unable, to produce a book for the final project that would tangibly engage with the material culture of wood.

Directly speaking in terms of my work, I have had to reflect on this need to shift and flux during this time, and what that means for the legibility and opacity of the archive and the specific collections I have been working with.

Thinking at the cellular level, the United States’ President Donald Trump has made remarks in reference to this notion of the “invisible enemy,” framing violence (the enemy) as something that cannot be seen, because we (non-scientists) cannot see the virus with our eyes. There is tension in the history of botany, especially in understanding the properties of wood under the microscope. Historically, botanists have grappled with the question of “how do we communicate the innards of wood without scaring people with what we find under the microscope?” Strategies in representing new scientific knowledge and its implications has always been really important.

I think this is an important question and I’m thankful to have the opportunity to vocalize my thoughts on this in relation to the work I have been doing on my thesis.

[CC]: We spoke of scale earlier on. So with this as a backdrop, how does chronology fit into the project? Do you think your work is speaking predominantly to the past, present or the future?

[FJ]: Wood specimens are often effective. When you look at specimens of fossil wood there is documentation of a millennia of growth within single rooms and buildings, spanning thousands of years or more than a millennia! That approaches the definition of deep time"—a scale so incomprehensible to humans. Chronology plays into how wood collections have changed over time from the 19th century to the present. You can clearly track changes in scientific epistemologies from Victorian empiricism onwards.

[CC]: What do you see as the life of this research beyond your thesis?

[FJ]: This project has been a largely critical endeavour, asking the fundamental question, how is wood read and curated? The creation of space in which the subject is both the science and the industrial product interests me. In the future, I would like to delve deeper into some of the referenced material and continue to get a better sense of what the documentation of xylaria means for environments slated for demolition or (re)construction.

6

Retreat

May 2, 2020, Zoom

Alexandra Tell is a writer, researcher, and curator whose current work investigates spatial concepts of the self in the 1970s, at the nexus of environmental psychology, pop psychology, and environmentalism. In her thesis, “Environments of the Self,” Tell considers how ecological, financial, and political insecurities prompted a retreat inward, not only to the climate-controlled and sound-proofed interiors of buildings, but towards a psychological interiority as well. The spaces collected in this thesis are at once psychical and psychic, contained by architectural boundaries of walls and ceilings, but reliant on the sensory as a form of ambient spatial control. Identifying episodes of environmental mood alteration and behavior modification that are test cases for thinking about the thresholds between body and environment, interior and exterior, “Environments of the Self” looks at where apparatuses of power emerge in a complex of bodies, spaces, sensory engagements, and architectures of mood.

Alex Tell, Environments of the Self, Advisor: Mark Wasiuta

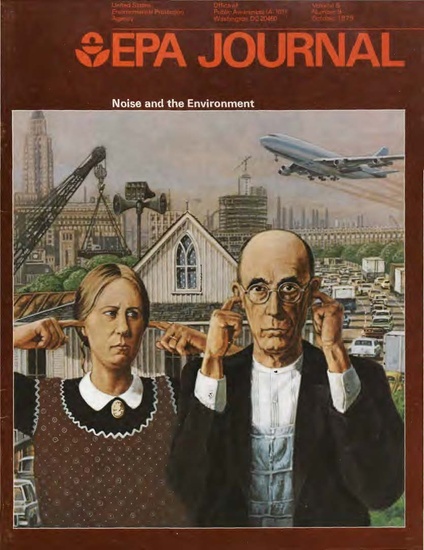

“Noise and our Environment,” illustration by Nathan Davies for EPA Journal, Volume 5, Number 9, October 1979.

[Hilary Huckins-Weidner]: One overarching concept in your thesis “Environments of the Self” that particularly drew me in was this notion of retreat and moving inward. In your work, you are exploring different episodes of internal retreat prompted by environmental threats. Do you think retreating into architecture or retreating into oneself, both as means of protection, are in a sense, a backward movement?

[Alexandra Tell]: I have been trying to deal with this tension in the movement inward, and not wanting to think of what I am researching as escapism. I think on the surface what I am looking at can be reduced to that, but it is important to realize that focusing on the psychological, focusing on one’s self or one’s psyche is not narcissism. I am trying to deal with what it means to confront oneself and want comfort and calm, while still understanding that there is a crisis happening on the outside.

Now I find myself relating a lot of this to our current moment, and it seems like everyone in our cohort is sort of reassessing their projects in the context of COVID-19. I am thinking a lot about the interior spaces we are all currently required to be in, and how there is acknowledgement of a crisis happening on the outside, but we remain necessarily removed from it. So I have been feeling this sort of cognitive dissonance between my existence in my home bubble and what is happening outside of my walls. That is what I mean by a tension between interior and exterior. Beyond thinking of the structures and architecture we erect to facilitate this, I am also thinking of the body as that perimeter, with the mind being the interior and the senses being a sort of perceptual boundary between us and the world.

[HHW]: Yeah, totally. Going back to what you were saying about this tension in relation to our current moment while looking through your research I was reminded of the term “shelter-in-place” and how its use in the context of COVID-19 has been so controversial. Politicians like Governor Cuomo associate it specifically with active shooter situations, so they were worried its use would create that extreme level of fear of the outside. It is interesting to consider the history of that phrase, which was originally put into use during the Cold War to request people to seek safety from atmospheric threats such as radiation and chemicals. The American Red Cross defines the shelter-in-place order as a request for residents to take refuge in a single small, interior room with little to no windows. A very specific architecture.

[AT]: Like bomb shelters.

There is this term that I read that I cannot get out of my head in relation to my work: “the ambivalent calm.” Paul Roquet, who writes about Japanese ambient media and culture in the 1960s and 70s, coined the term, and it is like this calm, an unstable calm, that registers while there is an external threat happening. That outside threat is the reason I am seeking calm, which creates a kind of psychic duality in that moment. It has been, in a way, such a haunting term for me, as it feels so relevant in terms of my work and the world currently.

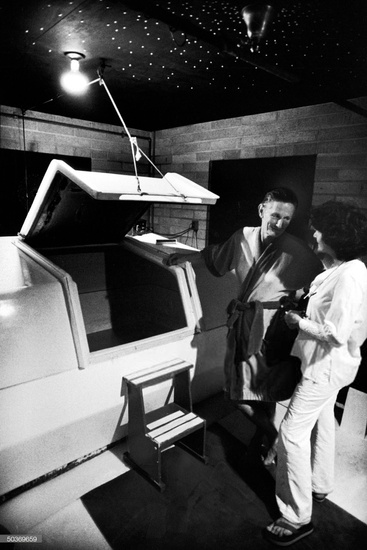

The inventor of the isolation tank John C. Lilly with his wife Toni after emerging from their at-home tank, September 1976. Photo by John Bryson (The LIFE Images Collection via Getty Images).

[HHW]: I want to talk more about this movement inward, but specifically in the context of the 1970s sensory deprivation tank, which was a commercialized and designed environment for internal retreat. I love the advertisements for them that you showed in your recent thesis presentation, and how they were clearly modeled after, physically and conceptually, space exploration technology of the time. The space exploration designs clearly flaunted ideas of the future based on an outward movement and a possibility of colonial expansion beyond the planet Earth. Yet, the sensory deprivation tank was for retreating from the outside and moving inward. What are your thoughts on this retreat into oneself taking place within designs that were influenced by the U.S.’s obsession with outer space and outward expansion?

[AT]: That is such an apt comparison because so much of the discourse around sensory deprivation tanks at that time, like that of psychonauts, was about deep exploration of the inner space, which was modeled after exploration of outer space. A lot of the same language was used, like “new frontiers” and “the unknown,” and so many links were drawn between outer space exploration and inner space exploration. I view it more in parallel terms rather than oppositional, like without there being any tension between the directions of those movements. I do not go too deeply into this connection to space exploration in my project, but I do think it is important because so much of the early research around isolation tanks was about space travel and figuring out how humans would fare in outer space.

Going back to the tension between inward and outward: one more thing I would like to reiterate, which is something that I have been trying to articulate for myself—so it is not a fully formed thought yet—but I am trying to think of this movement as not being unidirectional. The movement into the interior does not cut you off, but rather the interior is also working and is an environment that has been created to facilitate your retreat inwards.

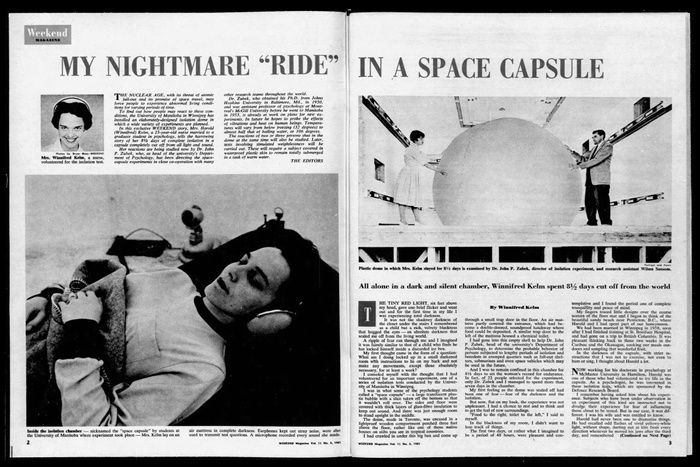

Winnifred Kelm, “My Nightmare ‘Ride’ in a Space Capsule,” The Ottawa Citizen, Jan 21, 1961.

7

Concrete

May 7, 2020, Zoom

Fernanda Gebaili Basile Carlovich has a background in architecture and is currently exploring other modes of practice through research, exhibitions, and writing. Carlovich researched the near simultaneous post-war construction of two, now abandoned domes designed by Oscar Niemeyer: Ibirapuera Park in São Paulo, Brazil, and Tripoli International Fair in Lebanon. Inspired by memories of climbing the dome in São Paulo, she explores the complex, twin histories of these sites. The transgressive act of climbing physically and politically re-signifies this “Traveling Dome.”

Fernanda Carlovich, Traveling Dome, Advisor: Felicity Scott

Youths scale the dome in Tripoli.

[Marco Piscitelli]: Your research situates the construction of these twin domes in the context of international developmentalism after World War II. While both projects sought to create an identity through a form that was simultaneously local-vernacular yet transnational, you stress that what’s at stake here is not transnationalism, but rather a specific “South-South” relationship. What is this “South-South” dynamic of the non-aligned nations and how is it manifest in these structures?

[Fernanda Carlovich]: There is a connection in the international relations of Lebanon and Brazil at the time of Niemeyer’s commission, since Niemeyer was a public employee working for the Brazillian state. He was contacted by the ambassador of Brazil in Lebanon in the name of the president; his travels happened as a sort of negotiation between these two countries. Besides that, as a communist architect he was very engaged with this idea of solidarity between nations that shared similar struggles. The President and Prime Minister of Lebanon, who were responsible for his commission, also engaged in this idea of neutrality and non-alignment. They were exploring the idea of non-aligned neutrality. It’s important to say that this is a moment when the world is divided between two poles. [These two states] were trying to create a third sort of alignment within this global power structure.

Aerial photograph, Tripoli International Fair.

Aerial photograph, Ibirapuera Park.

[MP]: Have the form and technics in these sibling-domes revealed anything about their particular South-South relationship or have you found in your research that their superficial similarity obfuscated crucial differences, imbalances, or particularities in each city?

[FC]: Both things happen. So on one side, you have the technique of reinforced concrete, which somehow fits neatly into the logic of a country that has this particular set of market and labor conditions. In that sense, the reproduction of Niemeyer’s technique was successful because these states were able to hire architecture and engineering offices and laborers that could manage to execute the concrete in the same way. I think that has a lot to do with the way the economy worked in both countries.

At the same time, there are very important differences in those contexts. First, even though both countries are searching for a national identity in this nation-building process, Lebanon had fewer than three years of independence while Brazil was independent for a much longer time. The search for identity in Brazil was an attempt to develop a national industry and to spread an image of a Country of the Future. In Lebanon, they were trying to get rid of the French mandate. [The dome’s construction] was thus a building of a national identity per se.

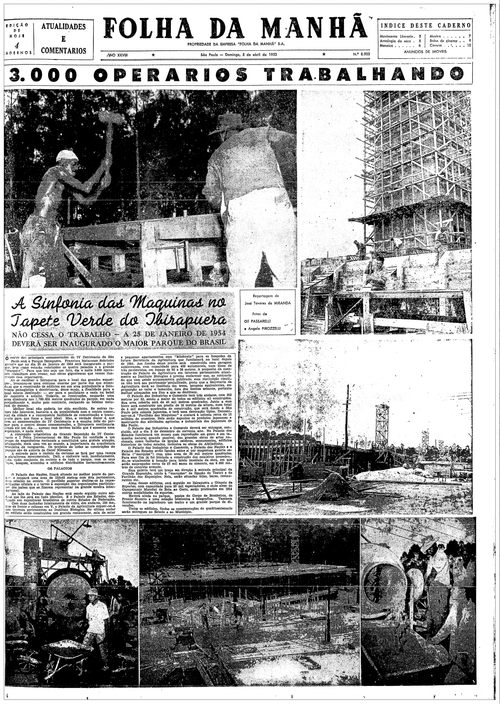

Construction photograph, Ibirapuera Park.

[MP]: Within the texture of your research lies a rhetorical and aesthetic doubling–mirroring, duplicity or duality appear often. In paired images of near-identical domes under construction, or in a diptych presenting both laborers and protesters climbing different concrete hemispheres, this kind of double-vision appears. How have you explicated this “South-South” relationship though this kind of formal or discursive mirror-play?

[FC]: First, this architecture is contextless. It’s abstract, it doesn’t fit into a broader context nor urban fabric. It spreads out as the Modern tabula rasa so you could simply place this concrete anywhere. There’s a sort of obstruction to this architecture that reflects the lack of contact with reality held by their Commissioners. There is a very strong disconnect between the potentials of design, of architecture, and the conditions of life. Second is the [passage] of time: these developing nations experience cycles of hope and cycles of collapse. You see things repeating. In Brazil, after the opening of Ibirapuera you had twenty years of non-investment in culture so the place was abandoned for a long time. Then in the 90s, you had an attempt to recover that space, but today, as [Brazil] doesn’t have a minister of culture anymore, the building is empty again.

Aerial photograph, Tripoli International Fair under construction

Aerial photograph, Ibirapuera Park under construction

[MP]: The first-person account of your travels is another mirror of a kind–one of your source materials is the travel diary of Oscar Niemeyer as he visited his sites in Brazil and Lebanon. What was your method for critically engaging in source material like this diary?

[FC]: The diary is a very interesting source. [Niemeyer] travels to Lebanon in 1962, in ‘64 there is the military coup in Brazil, and in ‘66 he writes [the diary] while exiled in France. In a very short period of four years, a lot happens both to him and with politics in Brazil. Of course, he is very egocentric; he [adds] this heroic tone to his own experiences. For example, he’ll say something like, “I travel across the globe without thinking of my own comfort because I need to spread my ideas of architecture.” You need to read those accounts with caution. At the same time, it’s a clear account of that [period].

Contemporary photograph, graffiti within the interior of the dome in Tripoli

[MP]: Another form of media your research utilizes is newspapers. In some of them, the construction of the domes is foregrounded by almost braggadocious reports on workforce numbers. How was labor depicted in this material and how do you position this material’s role in your research?

[FC]:[This sort of media] is very symbolic of that time in São Paulo. Ibirapuera Park was constructed to celebrate the four hundred years of São Paulo’s history; it was this huge gift to the people. All the media surrounding this construction highlight how big it was and the [vast] number of cement bags, of any material, used in its construction. It seems like the number of workers or was just another one of those statistics—those non-human statistics. [Newspaper reports] were not about who those people were or who were where they come from.

We know that at this moment in São Paulo there was significant migration from other states. It was also the moment where you start to have informal settlements. The beginning of the favelas in São Paulo is very related to this workforce arriving to construct [the dome]. This labor is depicted [in these contemporary newspaper accounts] as another statistic without any humanity.

Contemporary newspapers documenting construction of Ibirapuera Park.

Contemporary newspapers documenting construction of Ibirapuera Park.

[MP]: The act of climbing these structures is so poetically represented in your work. You reveal that cracks and old gunshots in the concrete are used as footholds to scale the domes. You depict climbing as an act of productive transgression in these cities. How do you situate your research practice in this political moment within Brazil?

[FC]: The act of climbing is what fascinated me about this building. For me, this is what’s most interesting about this whole history. The act of climbing was not predicted by the architect, but somehow it happens in all instances of these domes. To understand the building is to understand that it doesn’t belong to the history of the architect anymore. It belongs to a bigger set of claims. Climbing works as evidence that it’s not about the architect, it’s about the things that happen afterward. One thing that I thought was very symbolic was when I traveled to Lebanon and Brazil: both domes were empty. Of course, they have had very different afterlives, but today, for different reasons, they are both empty. This speaks a lot about the ambitions of the time [that they were built], this highly optimistic utopia that drove the construction of these buildings.

In short, in São Paulo the building is empty because we don’t have funding for culture. When Bolsonaro was elected, he dissolved the Ministry of Culture. After that, a lot of funding for museums and exhibitions just stopped. Now we depend on private funding, which is not that efficient in the context of Brazil. So the dome in São Paulo is empty. It’s very clear that it can translate what is happening on a bigger scale.

Construction photograph, laborers work on dome in Ibirapuera Park.

Photograph, protesters scale dome in Brasilia as part of a demonstration.

8

Translation

May 2, 2020, Zoom

Chenchen Yan is a writer and researcher with a background in Art History. Her thesis “Beyond Tradition and Modernity: the Formation of Chinese Architectural Discourse, 1928-1937” traces how the concept of *jianzhu (the Chinese equivalent of “architecture”) shifted from a craft to an art, a discipline, and a profession, as the young nation-state underwent tremendous socioeconomic and cultural transformations. By focusing on China’s “first generation of Chinese architects,” who received their architectural training in the USA, Europe or Japan, the research explores the role played by the cross-cultural circulation of aesthetics, technologies, information, and ideas in the formalization and legitimization of Chinese architectural practices and theories.*

Chenchen Yan, Beyond Tradition and Modernity: the Formation of Chinese Architectural Discourse, 1928-1937, Advisor: Reinhold Martin

[Lucia Galaretto ]: In Translingual Practice, literary critic Lydia Liu has argued that “One does not translate between equivalents; rather, one creates tropes of equivalence.” This understanding of translation was a keystone in your reading of the emergence of architecture as a discipline in early twentieth-century China, right?

[Chenchen Yan]: Yes! I was motivated by a kind of disciplinary, historiographical question: how to interpret a building or an architectural form without just saying “this looks like that.” In other words, I wanted to resist this common narrative of “foreign influence” by asking what was really modern about Chinese architecture at that time. Although it’s a mistake to say that nothing has been done in the field of Chinese architecture, I find that previous studies continue to reify the dualism of tradition and modernity. They reproduce the idea that traditional Chinese architecture was backward, and that only by importing or encountering the West was architecture in China finally modernized—with the imports of new technology, materials, etc.

To be clear, this equation of the modern with the West and the traditional with China’s past was also internalized by many of the first generations of Chinese architects. The question is what it meant to be a “Chinese architect” in the early twentieth century when the ideas of architecture—particularly Chinese architecture—had been subjected to the orientalizing gaze of the West. Until the establishment of the Society for Research in Chinese Architecture, China’s first research institute for architectural history, what the first generation of Chinese architects knew about Chinese architecture came exclusively from a handful of European and Japanese Sinologists, the most notorious of whom is Banister Fletcher. Chinese architectural discourse emerged out of a process in which China developed a sense of the self through the gaze of the West and Japan.

Basically, translation is an alternative concept to foreign influence, foreign impact, or copying. It not only gives agency to the first generation of Chinese architects but also takes account of their complicity in the perpetuation of Orientalized knowledge about themselves and the Western other. The concept of translation thus describes the complex processes of domination, resistance, and appropriation involved in the formation of Chinese architectural discourse.

My attempt to look at the invention of Chinese architectural discourse through the lens of translation is not so much to investigate how a form changed its meaning when it traveled from the West to China, but rather to acknowledge the colonial conditions while also putting pressure on the Chinese part in order to understand what it meant for those early characters educated in Western schools to become “Chinese” architects.

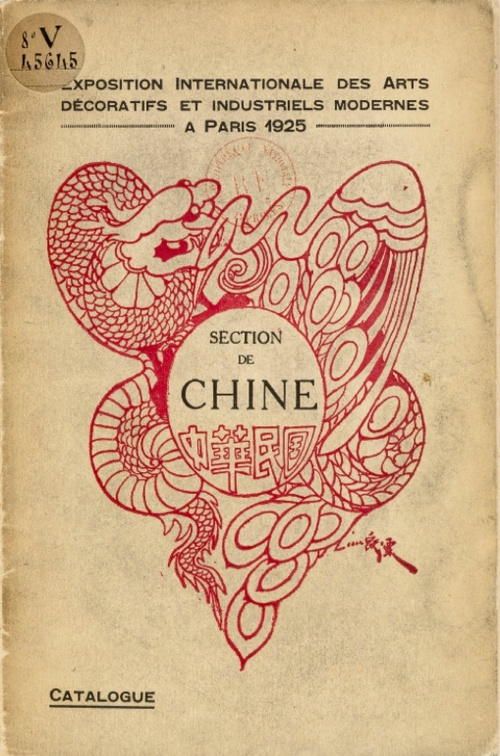

Catalogue for the Chinese Section, Exposition internationale des arts décoratifs et indus...

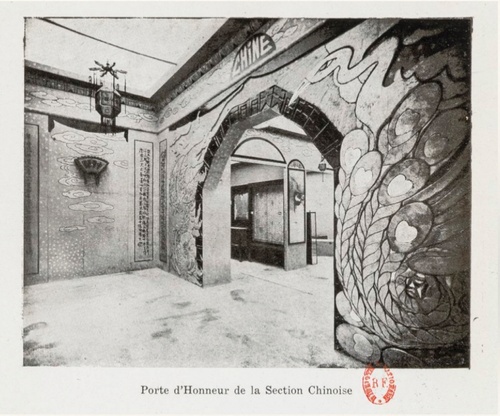

Chinese Section, Exposition internationale des arts décoratifs et industriels modernes

[LG]: In speaking to the entangled notions of tradition and modernity, you provide a particular reading of China’s contribution to the 1925 Paris fair as “self-Orientalizing”: both an embrace of exoticism and an attempt to define a new modern identity for the new-born Chinese state.

[CY]: Or as its architect put it, as a way to start a conversation but in a foreign language. Generally speaking, national identity is always about setting boundaries, right? You distinguish yourself from the other. But in the context of China, it’s really difficult to do so because the concept of architecture itself is caught in the East-West entanglement. So, it might seem ironic, but China’s self-representation at the 1925 Exposition did not counter but rather appealed to the colonial desire for the exotic. In creating architectural equivalents that could be understood by the West, the architect Liu Jipao advanced a vision of modernity that appropriated the Orientalist image of China.

Liu Jipao dressed in an imperial-style gown, Strasbourg, 1924.

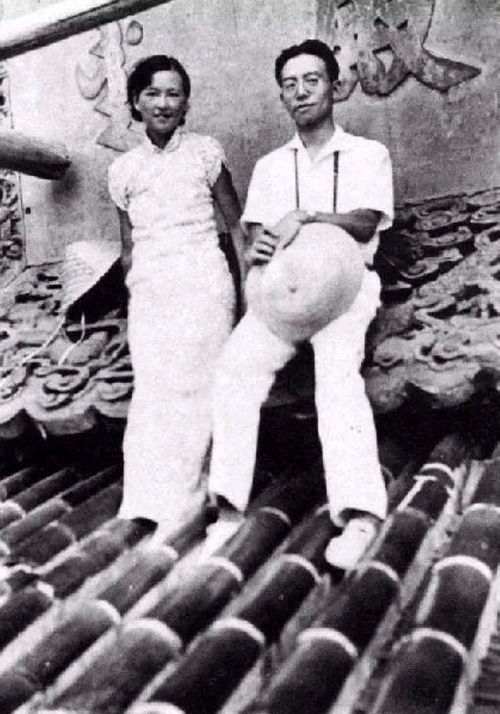

Liu went so far as to exoticize himself. He appears in a 1924 group photo of artists and officials dressed in an elaborately embroidered imperial-style woman’s gown. But he wasn’t the only one. There was a lot of self-orientalizing symptomatic in other contexts. Take the case of Liang Sicheng and Lin Huiyin, a couple of US-educated architects whose documentation of traditional Chinese architecture in the 1930s has laid the foundation for Chinese architectural history.

This is a picture taken at a ball during their studies at the University of Pennsylvania. I discovered this photo recently and I’m still looking for a way to address it, but it also speaks to the self-orientalizing question. It would go something like: in a foreign land, you are to perform your traditional Chinese self. To be honest, these are good costumes, but they’re far from authentic—the abstract patterns are makeshift imitations of traditional clothes.

Liang Sicheng and Lin Huiyin in costume for the 1926 Beaux-Arts Ball, “L’Impressionistique,” a...

Liang Sicheng and Lin Huiyin.

[LG]: But it’s also very interesting to see that in China, they wouldn’t use—

[CY]: No, no, they would normally wear Western suits in China to show their authority as Western educated scholars.

Liang’s and Lin’s work might appear to be purely about traditional Chinese architecture and architectural identity: they are conventionally described as conservative because of their focus on the Chinese style and the so-called national essence. In that narrative, you can see the clear—apparent—divide between the traditional side and the modern side, those architects who tried to hybridize Chinese architecture with foreign Western art forms.

But, as I looked deeper into this “traditional side,” I found that actually the so-called “Chinese” architecture tradition was a modern construction, as regards the historiographical methods and narratives they used in their research and writing of Chinese architectural history. Liang and Lin invented a system of talking about, commenting on, and analyzing traditional Chinese architecture that did not simply historicize but recreated and modernized traditional Chinese architecture. Eventually, I hope to deconstruct this dualism of tradition and modernity by arguing that tradition and modernity in Chinese architecture were mutually constituted: modern Chinese architecture defies the essentialist understanding of modernity as a radical break with the past.

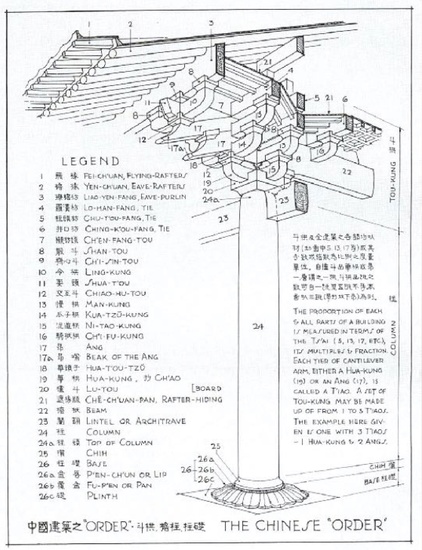

Liang Sicheng, The Chinese “Order,” from Liang Sicheng’s posthumous publication, A Pictorial History of Chinese Architecture: a Study of the Development of Its Structural System and the Evolution of Its Types, (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1984).

[LG]: I know you are using the trope of translation to interrogate a specific episode in the history of architecture, but I wonder what would something like that mutual constitution look like in our current globalized world?

[CY]: If the translation is one of the fundamental ways in which we recognize and understand the other, then I think it is important to attend the two directions in this process, and how power relations might shift the dynamic of translation. I think the current trend in our field is to recognize and to emphasize the global network of exchange behind each work, as a way to decenter the figure of the author. I’m thinking here, too, of Donna Haraway’s idea of a significant other, the coming together of non-harmonious agencies that accounts for both their disparate histories and their entangled futures, opening up the possibility for an ethical recognition of otherness.

9

Satellite

May 4, 2020, Zoom

Jumanah Abbas is a writer and researcher. Her thesis, “On Frontiers of a Vertical Dimension” departs from an examination of the Arabsat-1A launching to rethink the political strategies considered for extracting, managing, and ordering unfamiliar frontiers.

Jumanah Abbas, On Frontiers of a Vertical Dimension, Advisor: Felicity Scott

[Nadine Fattaleh]: Your thesis, which takes the Arab world and Palestine as its primary geography of inquiry, is entitled “On Frontiers of a Vertical Dimension.” The vertical allows you to explore various aspects of territorialization that exceed what is commonly represented on a two-dimensional map or plan. Can you explain a bit about what is at stake in rendering visible the third, vertical dimension?

[Jumanah Abbas]: In exploring the vertical dimension, I try to understand territory not as a cartesian plane, but rather as a bounded volume where infrastructures of communication operate at multiple, different strata through satellite orbits, electromagnetic spectrums, and the air that surrounds us. The vertical can be understood, broadly, as a dimension that is still underexplored, a frontier open to extraction, management, and ordering. I tell two distinct stories about techno-politics of the vertical domain. I start with the first pan-Arab satellite, ARABSAT, that sought to facilitate the free flow of information across the Arab world. By examining the material processes behind the satellite launch in 1985, I unlock how territories were imagined and grasped through mechanisms of calculation that promised Arab cultural autonomy and enabled new forms of control in the vertical dimension. Next, I move on to investigate telecommunication networks that facilitate phone calls in Palestine today. Here, the notion of the frontier also places my understanding of territorial practices in Palestine within a comparative settler-colonial framework. The vertical politics of transmitters that produce variegated cell phone coverage across the occupied West Bank are entangled in complex ways with more visible, and perhaps horizontal, manifestations of Israel’s infrastructural violence and control through the technologies of checkpoints, “security” walls, and settler only roads. By bringing together these two stories, I do not intend to draw direct comparisons. Rather, I underline how claims to deterritorialize horizontal space through the politics of the vertical are always subject to contingent conditions on the ground informed by political, juridical, technological, and economic concerns.

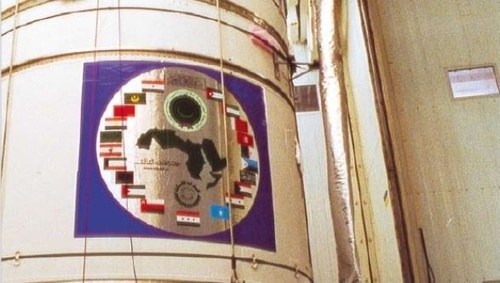

ARABSAT Satellite Launch, Photo Source: https://www.slideshare.net/arabsat/arab-sat-booklet-in...

Al Faysal Magazine, issue 102 (September 1985).

[NF]: One image in your collection that caught my attention is the inscription of the “map” of the Arab world on the satellite, surrounded by images of the corresponding flags. Can you elaborate a bit on this image, and what it means to your project?

[JA]: The image is taken from ARABSAT’s first satellite launch. ARABSAT, the Arab Satellite Communications Organization, was first explored by the Arab League in 1967. The project would prove to be a prolonged endeavor that culminated in the launch of the first geostationary communication satellite in 1985. The story of ARABSAT involves a diverse array of state actors, technical experts, and international organizations that saw the possibility of imagining a unified Arab world through the openness, connectivity and free flow of information afforded by the vertical domain of the satellite and its ability to overcome rugged terrains and physical borders. The stated ambition was to create a pan-Arab telecommunication network that was both fully operational, completely autonomous and helped to realize a notion of Arab unity from the Northern border of Syria to the southern border of Sudan. The image of the logo of ARABSAT boldly marked on the external surface of the satellite indexes the promise embedded in the project. The social, economic, and national differences of the Arab states are suspended in the flags of each country that eclipse the map of the Arab world as a territory devoid of internal borders or demarcations. The aesthetic appeal of the logo represents the possibility of Arab unity and sovereignty that was a driving force of the project.

ARABSAT was an extremely complex technological endeavor. The microwave linkage needed to cover the entire Arab region was estimated, the radio relays were pre-planned, the signal traffic was predicted, and documents with specific technical and infrastructural requirements for the ground reception stations circulated around the Arab governments. The imagined continuous territory of the Arab world was, in reality, not as homogenous as the logo that represented it. The calculative and material processes encoded politics into the neutral promise of the free flow of information, enacting new modes of governmentality across the Arab world in a third dimension.

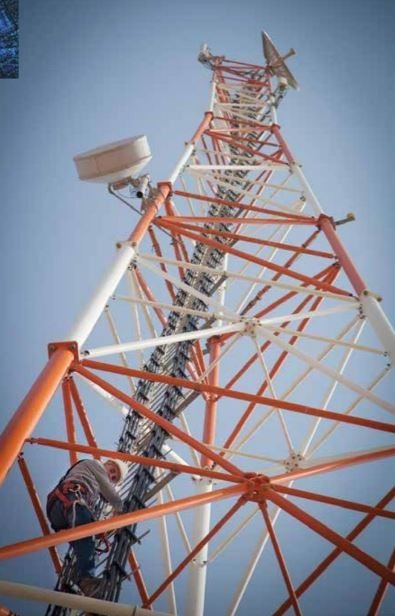

Telecommunications Tower in Palestine. Photo source: http://www.thisweekinpalestine.com/teleco...

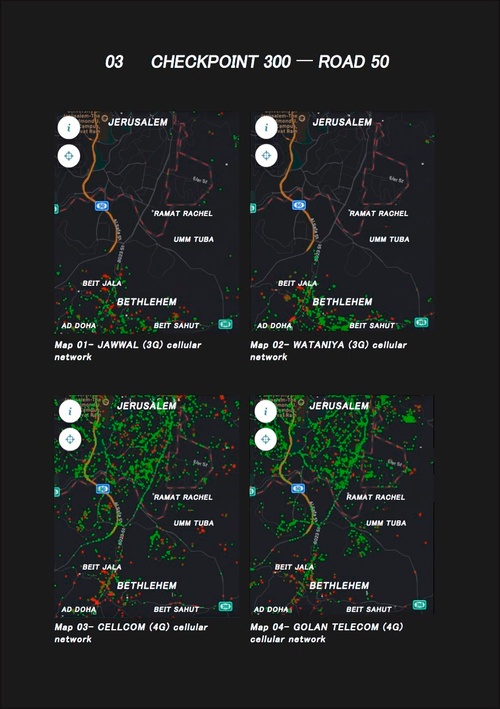

Cell Phone Coverage in Jerusalem and Bethlehem.

[NF]: With the case of the telephone network that operates on the ground in Palestine today, you move from questions of the aesthetic, which inform your reading of the promise of ARABSAT, to questions of the affective that ground your understanding of infrastructure in how people experience and feel everyday life. Can you expand more on this?

[JA]: In the West Bank today, cell phone coverage provided by Jawwal, the national phone operator in Palestine, is extremely variegated because frequency and bandwidth cannot be made to conform to the topological twists of space informed by Israel’s juridico-political practices. I made some maps that attempt to locate phone receivers and other telecommunication infrastructures. With this, I hope to produce a cartography that renders visible what scholar Helga Tawil-Souri notes of the politicization of the electromagnetic spectrum and its mobilization as a territorial asset. I am aware that maps are static objects that anchor relationships in space and time. My work also attempts to shed light on the lived realities of Palestinians and their experience with phone calls in Ramallah-narratives that unfold how territories are not fixed in space, but rather constantly shift and recast. Communication infrastructures allow for people to make phone calls, but how and when they receive coverage, at what speed their internet operates, and what prices they pay for the service all matter. The affective experience of telecommunication in Palestine emerges across the uneven development of the city of Ramallah, where Jawwal’s signal coverage is not just bounded by the limited frequency bandwidth and the number of subscribers, but also by the main roads connecting the nearby settlements, Beit El and its military base and post, and neighboring Qalandniya checkpoint. The spatial fracture of Ramallah is multiplied by the thousands of geographic cellular phones that receive contingent coverage as a result of the politics enacted in the vertical domain.

[NF]: Your work gives a lucid account of telecommunication infrastructure across the imagined, abstract, homogenous vertical domain and the real, messy, patchy horizontal domain. What are some of the questions you find are still unresolved in the work?

[JA]: A lot of the questions that came up in the project forced me to reconsider many of the supposed binaries that the story of telecommunication infrastructure is often narrated through. The first is obviously the vertical and the horizontal, or volume and plane. I also question the supposed opposition between technology and politics, aesthetics and function, lived experience and static representation. The stories I have told imagine the vertical frontier as a form of sovereignty that is always undermined by the materiality of territory. What remains unresolved for me is this question of vertical sovereignty and how it might be brought down to the ground.